Early America inherited much of Britain’s bloodthirsty but arbitrary approach to the death penalty, with theoretical penalties for things like theft and rebellious children that were rarely carried out. However, executions did happen for crimes short of murder: Death was a common penalty for repeated theft, and in 1644, a couple was executed in Massachusetts for adultery.

Following the revolution in 1776, states dramatically decreased the number of crimes punishable by death. (The vast majority of executions in the US have always been carried out by individual states, not the federal government.) There was a general movement to make punishments more proportional, and the number of executions fell somewhat despite rapid population growth.

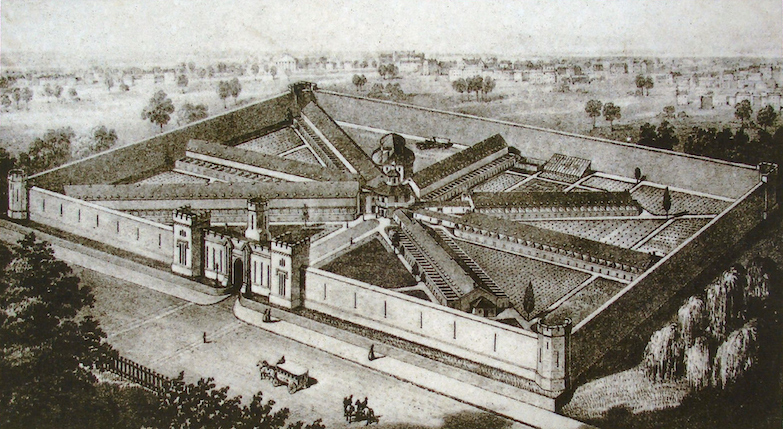

At the start of the 1800s, some religious leaders and enlightenment thinkers started to push for complete abolition. Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the declaration of independence, pushed for imprisonment as an alternative, leading Pennsylvania to build the world’s first “penitentiary”—so-called because of Quaker beliefs in the value of penitence.

Gradually, a few states started to abolish the death penalty. Michigan never executed anyone and abolished in 1847, followed by Rhode Island (mostly) in 1852 and Wisconsin in 1853.

The number of executions rose rapidly between 1800 and 1900. However, there’s no cultural shift to explain here, it’s entirely due to the rising population—the number of executions per million people was slowly dropping.

| Year | Executions | Population (m) | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 20 | 5.3 | 3.8 |

| 1850 | 50 | 23.1 | 2.2 |

| 1900 | 120 | 76.2 | 1.6 |

Abolition was disrupted by the Civil War and reconstruction, though Maine did ban the death penalty in 1887.

The start of the 1900s was the beginning of the Progressive era. Ten states abolished the death penalty (Minnesota, North Dakota, Colorado, Oregon, Washington, Kansas, South Dakota, Missouri, Arizona, and Tennessee), and the number of executions plateaued.

However, after WWI, support for capital punishment rebounded, and all but two of these states reversed their abolition. The 1930s saw the highest absolute number of executions in US history.

From the 1930s to 1950s, culture gradually came to view hanging as barbaric, in part due to the botched execution of Eva Dugan. Most states replaced hanging with poison gas, electrocution, or lethal injection, which were less disturbing to onlookers.

After the end of WWII, the number of executions gradually fell, reaching zero in 1967. At this time, the U.S. was even cited as an example of countries moving away from the death penalty in debates in the UK.

Why did this fall happen? One cause was an increased number of states abolishing the penalty, which Hawaii, Alaska, Delaware, Michigan (again), Oregon, Iowa, New York, West Virginia, Vermont, and New Mexico all did between 1957 and 1969. Another cause was that even in states where the death penalty was legal, it gradually became rare for prosecutors to seek it.

There were no executions in the United States between 1967 and 1977.

Along with this decline in executions, the death penalty was also quickly becoming less popular. In 1966, a Gallup poll found for the first time (and only time, to this day) found that more Americans opposed the death penalty than supported it.

In 1958 in Trop v. Dulles, the Supreme Court held that the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of cruel and unusual punishments held for “evolving standards of decency”. This led to a suspicion that the death penalty might be unconstitutional.

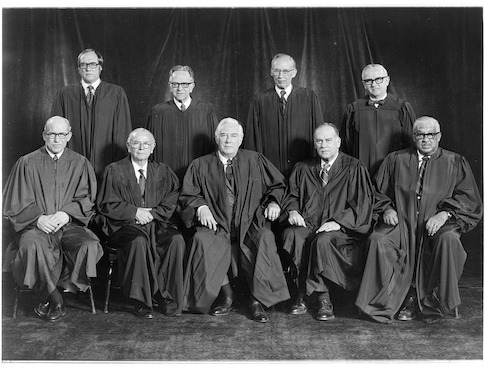

In 1972 in Furman v Georgia, the Supreme Court held that all current death penalty schemes did indeed violate the Eight Amendment. This decision was extremely disjoint, coming 5-4 with no consistent rationale and all nine justices writing separate opinions. Two justices in the majority wrote that the death penalty itself was cruel and unusual, while three others were more narrow, saying that current statutes were too unreliable and arbitrary.

As a glimpse of the boundaries of elite opinion at the time, the four dissenting judges in Furman—all appointed by President Nixon—each stated they were personally opposed to capital punishment and would vote for abolition if they were on a state legislature.

Following Furman, there was a large jump in public support for the death penalty. I thought that this might be a backlash to Supreme Court overreach, however, a small and highly biased sample of older Americans I happen to know my sources tell me that nobody cared about that and it was more about increases in crime.

Furman created a de-facto moratorium. Many suspected that the death penalty was gone for good, but it wasn’t entirely clear if reformed systems could pass constitutional muster. Between 1972 and 1976, 37 states created new death penalty laws. Reforms included separate guilt and sentencing phases, and more uniform standards to guide juries and judges. The Supreme Court invalidated laws in North Carolina and Louisiana that imposed the death penalty for all capital crimes.

In 1976 in Gregg v. Georgia, the court confirmed 7-2 that some of these reformed laws were constitutional. (The two dissenters are the same justices who wrote that all executions were unconstitutional in Furman.)

Up until these court decisions, America’s history isn’t all that different to that of the U.K. or France. In fact, support for the death penalty at this time was substantially lower in the U.S. than in Germany, the U.K., or France.

Executions resumed in 1977 and increased up until around 2000. Popular support for the death penalty also dramatically increased, peaking at around 80% in 1996.

The surge in popular support for the coincided with a huge increase in violent crime. The homicide rate—already much higher than the European countries we looked at—more than doubled between 1963 and 1975.

Here’s an animation that shows what states formally banned the death penalty (black) from 1970 to 2021 (if you can avoid screaming in frustration at how slowly it moves):

Since 1972 there have been at least 20 ballot initiatives in different states to either abolish the death penalty, reinstate it, or change the scope of applicability.

- Arizona in 1992.

- California in 1972, 1978, 1990, 1996, 2012, 2016, and 2016 again.

- Colorado in 1974.

- Florida in 1998 and 2002.

- Massachusetts in 1982.

- Nebraska in 2016.

- New Jersey in 1992.

- Ohio in 1994.

- Oregon in 1984 and 1984 again.

- Washington in 1975.

- Wisconsin in 2006.

- Wyoming in 1994.

In every case, the vote went in the pro-death penalty direction, e.g. against abolition, in favor of bringing the penalty back, in favor of applying the death penalty to more crimes, in favor of reducing the governor’s ability to commute sentences, or in favor of shortening the appeals process. One of the closer votes was the 2016 initiative to ban the death penalty in California, which failed 53% to 47%. (Governor Newsom imposed a moratorium in 2019.)

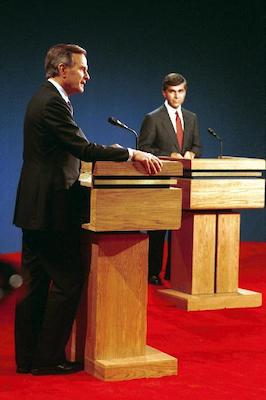

The politics of the death penalty were laid bare in 1988. Michael Dukakis, the Democratic governor of Massachusetts was in a presidential debate when he stated—consistently with his abolitionist position—that he would not support the death penalty for someone that raped and murdered his wife. His poll numbers dropped by 7 points overnight and he went on the lose the election by 8 points.

Dukakis’ example was surely on Bill Clinton’s mind in the 1992 presidential election campaign, when he specifically flew home to Arkansas to confirm an execution. The man was Ricky Ray Rector, who had essentially lobotomized himself in an attempted suicide after murdering a man and shooting a policeman. Rector had so little understanding of what was happening that he saved the dessert from his last meal “for later”.

Over the years, the Supreme Court has continued to narrow the scope of applicability of the death penalty.

- Coker v. Georgia (1977) prohibited the death penalty for the rape (without murder) of an adult woman.

- Godfrey v. Georgia (1980) held that a murder being “outrageously or wantonly vile” was not sufficient cause for the death penalty.

- Enmund v. Florida (1982) held that the death penalty cannot be applied to someone who didn’t kill anyone, try to kill anyone, or intend to kill anyone, even if they were part of a crime that resulted in someone dying. This was later clarified in Tison v. Arizona (1987) to include behavior that was reckless and indifferent to human life.

- Ford v. Wainright (1986) held that it was unconstitutional to execute the insane.

- Atkins v. Virginia (2002) prohibited executing someone who is intellectually disabled.

- Roper v. Simmons (2005) prohibited the death penalty for any crimes committed by someone under the age of 18.

- Kennedy v. Louisiana (2008) prohibited the death penalty for the rape of a child.

Eventually, in the 1990s, things started to move against the death penalty.

In the early 1990s, the homicide rate finally began to fall, dropping by about half by 2000 and then stabilizing at a similar level to the 1950s and 1960s. (But keep in mind that level is still much higher than other Western democracies.)

Starting in 1995, support for the death penalty decreased. It fell from a peak of 85% to around 56% in 2020, only slightly higher then France or the U.K..

Starting in 2000, the number of executions fell, decreasing from a peak of almost 100 per year to around 20 per year now. There seem to be two major reasons for this fall:

-

Juries are more hesitant to issue death penalty convictions. This is partially spurred by the dozens of people who were sentenced to death and then later exonerated, something that become much more common after the arrival of DNA evidence. There have been a few possible wrongful executions. Juries also increasingly choose life without the possibility of parole, an alternative sentence now available in more states.

-

Many states have added extra layers of protection for defendants charged with the death penalty, such as providing better defense lawyers, and more appeal opportunities. These reforms seem often motivated by a concern that the Supreme Court’s gradually increasing standards might otherwise invalidate all convictions. These protections have made it more difficult and expensive to get the death penalty, meaning fewer prosecutors seek it.

As of 2021, the situation is:

- In 27 states, the death penalty is formally abolished or was never created in the first place.

- In 7 states and the federal government, the death penalty is legal but there is a formal moratorium.

- In 10 states and the military, the death penalty is legal, and there is no moratorium, but no executions have happened in the last 10 years.

- In 13 states, the death penalty is actively used. (Arizona, Idaho, Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida)

- Ohio is complicated.

While most executions are done by the states, the death penalty remains legal at the federal level. Nevertheless, between 1972 and 2000, there were no federal executions. Between 2001 and 2003, there were three, including Timothy McVeigh who killed 168 people in the Oklahoma City bombing. Between 2004 and 2019, there were again no executions.

Still, all this time, US federal courts continued to sentence people to death. President Trump resumed executions in July 2020, and 13 were carried out before President Biden imposed a moratorium in early 2021.

Summary: In the 1960s, public support for the death penalty was unusually low compared to the other countries we looked at. Executions gradually slowed and stopped in 1967. The Supreme Court flirted with declaring the death penalty unconstitutional in 1972 but confirmed it was legal in 1976. Following this, violent crime, executions, and public support for the death penalty all surged. Starting in the 1990s, violent crime receded, reforms made the death penalty more difficult to carry out, and the number of executions waned, along with popular opinion. In 2021, a small majority of the American public supports the death penalty.

Compared to Germany, France, or the U.K., the history of abolition in the U.S. is bewilderingly convoluted. It’s odd that the penalty would slowly become less popular, stop being used for 10 years, and then suddenly rebound for 25 years. Also, it’s impossible to keep track of the number of states that banned or restricted the death penalty, but then it would get un-banned or un-restricted, either because different politicians won the next election, or because of a popular referendum.

Next time, at last, we’ll try to find patterns in all these histories we’ve gone through.

The death penalty as a lens on democracy

- Introduction

- How Germany banned the death penalty

- How the United Kingdom banned the death penalty

- How France banned the death penalty

- How the United States didn’t ban the death penalty

- Which way the arrows? (soon)