When Beccaria wrote On Crimes and Punishments in 1764, there were around 150 crimes punishable in Britain by death. This “bloody code” included crimes as small as the theft of some items worth 1 shilling. For context, a skilled worker at the time could earn around 20 shillings in a week, and 1 shilling in 1764 inflation adjusts to £7.25 ($9.75) today.

This was an embarrassment to the British Crown, always eager to see itself as superior to the continent. Britain had abolished torture, which most of Europe had not. On the other hand, while much of Europe maintained the death penalty, it was rarely applied to crimes like petty theft.

It’s still debated why so many offenses were punishable by death. One popular theory is that it was driven by social disorder resulting from the industrial revolution. I find this theory strange since many of these laws predate the industrial revolution’s start around 1760. Another theory is that power in Britain came from Parliament, whereas in much of Europe it came from monarchs who didn’t need to worry about a backlash from the public.

Most potential executions weren’t carried out, due to slack in the system: Prosecutors, victims, and juries often tried to convict on lesser charges. There were legal loopholes and various clemencies. When people were actually executed, it seemed less due to their crimes and more to bad luck.

Some did defend the system. William Paley said you could deter crime by either having capital punishment for few offenses and always carrying it out, or having it for many offenses and carrying it out rarely, and the latter would be more deterrent. This is a kind of prelude to Gary Becker’s thinking about crime and expected value theory in the 1970s.

An initial push against this system was led by Samuel Romilly, the handsome fellow above. Romilly was a self-educated lawyer who grew up in a French family in London, traveled in Europe, and also opposed the slave trade. He did not oppose the death penalty for murder but argued it was ridiculous to apply such varying penalties to the same crimes. While many other members of Parliament were hostile to his suggestions, he managed to repeal the death penalty for things like pickpocketing. He also obtained a ban on execution by drawing and quartering (bleak link; do not click).

The movement against capital punishment was strengthened by Jeremy Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism. In 1832, Parliament passed the Punishment of Death, etc. Act, which eliminated the death penalty from around 2/3 of offenses (and apparently did not suffer from overthinking when being named). Finally, the reformist Whig leader John Russell convinced even the House of Lords that the current system was a disgrace, and in 1837 the “bloody code” was dismantled, leaving the death penalty only for serious crimes.

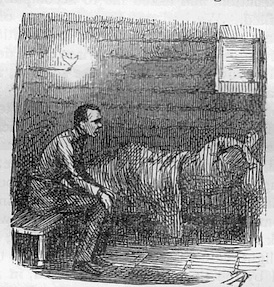

In 1840, William Makepeace Thackeray published Going to See a Man Hanged. He describes setting out on an adventure, and gradually becoming horrified at the atmosphere outside the prison with people selling food, telling jokes, and climbing in trees. He says of the condemned man, “it is painful to see how he fastens upon everybody who approaches him, how pitifully he clings to them”. At the end of the day, he says “I feel myself ashamed and degraded at the brutal curiosity which took me to that brutal sight”. A sign of a changing culture, this is supposedly the first time pity for a murderer appeared in print.

Public opinion continued to move against the death penalty. Improvement in policing meant more crimes were solved, and more prisons meant other penalties existed, meaning there was less of a need to “make an example” of people. Further reforms followed. By the 1860s, the death penalty was in practice only applied for murder. In 1868 Parliament passed A Bill to Provide for Carrying Out Capital Punishment in Prisons (rather than outside them), another testament to the trend of laws with very explicit names.

At this point, movement slowed. John Stuart Mill had earlier opposed the death penalty but felt that reforms justified it. Speaking of continental Europe (axiomatically worse than Britain) he says there are “great and enlightened countries, in which the criminal procedure is not so favorable to innocence, does not afford the same security against erroneous conviction, as it does among us.” That is, it was OK to have the death penalty because Britain’s awesome legal system meant an innocent person could never be condemned.

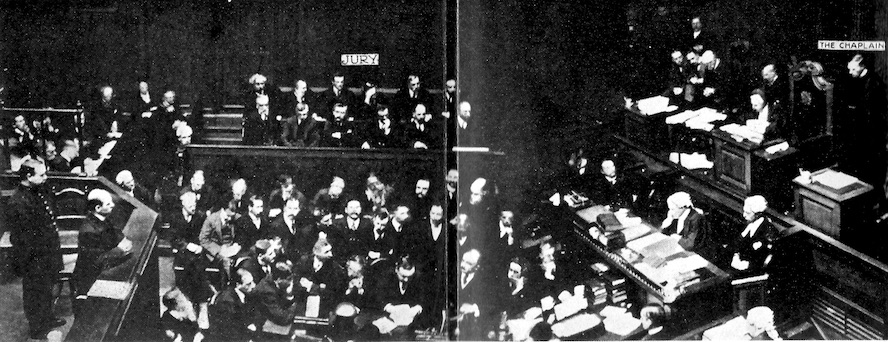

Here’s what a court looked like handing down a death sentence in 1912:

Not much changed until 1923 when the Labour party made abolition an explicit position. This led to the creation of a select committee on capital punishment, but this was stacked somewhat in favor of retention, leading it to a divided verdict and no action from the Labour government.

Then came Sydney Silverman, an interesting character who went to jail as a conscientious objector during WWI, lectured at the University of Finland, moved back to Liverpool, became a lawyer, joined the Labour party, and won an election to represent Lancashire in Parliament in 1935. Silverman was a militant socialist. His personality was described as “opinionative, dogmatic, assertive, and quarrelsome” by a Labour ally. He was so disliked by Conservatives that several who privately favored abolition refused to support it in public simply because they hated Silverman so much.

In 1938, a Conservative member of Parliament suggested a motion to abolish the death penalty. This was done as a “free vote”, meaning members weren’t bound by the position of their party. The vote passed 114-89. Except this was all non-binding, and so Chamberlain’s government simply ignored it.

As elsewhere, WWII paused any movement on death penalty abolition (and reversed Silverman’s pacifism). When Labour formed a government after the war, they didn’t have the nerve to include abolition in their big criminal justice bill, probably because support for the death penalty had risen during the war. Still, in around 1947—I can’t figure out the exact date—they allowed it to be raised as an independent issue. Many spoke that the moment was not right, with the public strongly opposed. But Silverman argued passionately for ignoring public opinion:

We are not delegates; we are not bound to ascertain exactly what a numerical majority of our constituents would wish and then to act accordingly without using our judgment. Edmund Burke long ago destroyed any such theory. We are not delegates. We are representatives.

The vote passed 252-222 and the bill went to the House of Lords. At the time, many understood the Lords to have a special prerogative to examine only certain bills, somewhat akin to how the Supreme Court functions in the United States. So it was controversial that they would even consider rejecting this bill. But they rejected it anyway, 181 to 28, partially justified by the fact that this was not an “official” Labour bill.

After this rejection, the House of Commons passed a compromise bill that would have restricted but not eliminated capital punishment. In the House of Lords, Churchill denounced it as out of step with the nation, and the compromise was also rejected. Finally, Labour set up a special commission that met for four years before reporting in 1953, at which point Churchill was again in government. He delayed debate to 1955, and those recommendations were rejected, too.

Public opinion in this era may have been influenced by the case of Timothy Evans, who was executed in 1950 for the murder of his wife and daughter. After their death, he made suspicious and contradictory statements about trying to abort a new baby (abortion was illegal) eventually saying that his neighbor John Christie had offered to perform an abortion, then said she died in the process, and Evans should leave London for his own safety. Some speculate that Evans was mentally limited and not capable of fully understanding what was happening. Three years after the execution, it emerged that Christie was a serial killer and had murdered several women in the same building. This possible execution of an innocent man was in the news for years. (An official report in 1966 came to the strange conclusion that Evans probably killed his wife but that Christie had killed the daughter. Nevertheless, the Queen gave Evans a posthumous pardon.)

In 1956, Silverman was able to get a five-year moratorium on capital punishment passed 286 to 262, with support from Labour and a growing number of Tories. In committee, various amendments were proposed. These were defeated, except one that would keep the death penalty for murder committed by someone already serving a life sentence. When Silverman couldn’t remove this amendment, he used a series of arcane motions to remove all the words from the amendment except for the meaningless fragment “provided that this”. Even many in Labour thought this was beyond the pale, but it worked and the bill passed.

Again this bill went to the House of Lords. Based partially on the earlier controversy, reforms had been passed to limit their power to reject most legislation. But no matter, they rejected it anyway.

Eventually, the Queen publicly called to limit the scope of capital punishment. The Tories passed the Homicide Act of 1957 which reduced the death penalty to specific types of murders, e.g. murder during theft or murder of police. The goal of these limits was to stave off calls for complete abolition. However, they were immediately criticized. For example, people questioned why murder in the course of rape was excluded.

Finally, in 1964, Labour obtained a small majority. There was a fierce debate, in which several conservative members of Parliament described converting to abolition. In the end, they easily passed a five-year moratorium. In a sign of the changing times, this got an even larger majority in the House of Lords. Silverman did not quite live to see abolition being made permanent in 1969, with support from the leaders of all three major parties.

Various conservatives have made attempts to reintroduce capital punishment in 1973, 1975, 1979, 1983, 1987, 1988, 1990, and 1994, but these were defeated with ever-larger majorities.

In 1998, the Human Rights Act (HRA) completely abolished capital punishment (it was still in principle allowed for military executions). In 2002, The UK signed protocol 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), meaning that the UK could not reinstate the death penalty without leaving the EU.

In the last poll I could find, from 2019, public support was still just above 50%. This might seem to contradict all the articles from 2015 titled “Support for death penalty drops below 50% for the first time”. I think those articles are misleading—the data comes from the British Social Attitudes survey where you can easily see that the number of people who supported the death penalty was still clearly larger than the number who opposed it. It’s just that active support was less than 50% due to the fact that 18% of people have no opinion. My chart above shows support among people who do have an opinion.

Anyway, now that the UK has left the EU, could it reinstate the death penalty? As far as I can tell, in principle, a simple act of Parliament could overturn the Human Rights Act and put the death penalty back in place. But in negotiating the post-Brexit EU-UK trade agreements, the EU insisted that the UK continue to enforce the European Convention on Human Rights. If the UK wanted to put the death penalty back in place, it would have no trading agreement with any of the EU.

Summary: Shortly after WWII, the population strongly supported the death penalty, yet leftist elites united behind abolition and rightist elites were divided. After a series of battles between the House of Commons and the House of Lords a ban finally went in place in 1964. Public support for the death penalty was stable (and positive) for around 30 years, and then started slowly declining to something near an even split today.

What does it all mean? Well, it’s hard not to be impressed by how… irrelevant public opinion seems to the fierce battles between different elites. It’s also striking how the UK, like Germany, moved to take the issue out of the democratic domain. But let’s save the theorizing to after we’ve covered France and the U.S.

The death penalty as a lens on democracy

- Introduction

- How Germany banned the death penalty

- How the United Kingdom banned the death penalty

- How France banned the death penalty

- How the United States didn’t ban the death penalty

- Which way the arrows? (soon)

Data and sources

| year | support | oppose | source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1938 | 49 | 40 | SOC |

| 1958 | 79 | 11 | INRA |

| 1964 | 67 | 21 | SOC |

| 1966 | 76 | 18 | SOC |

| 1977 | 81 | 17 | IPSOS |

| 1978 | 77 | 21 | IPSOS |

| 1979 | 74 | 23 | IPSOS |

| 1981 | 78 | 19 | IPSOS |

| 1986 | 73 | 19 | BSAS |

| 1987 | 72 | 18 | BSAS |

| 1989 | 73 | 19 | BSAS |

| 1990 | 70 | 21 | BSAS |

| 1991 | 58 | 29 | BSAS |

| 1993 | 73 | 19 | BSAS |

| 1994 | 69 | 21 | BSAS |

| 1995 | 68 | 21 | BSAS |

| 1996 | 67 | 20 | BSAS |

| 1998 | 59 | 25 | BSAS |

| 1999 | 58 | 28 | BSAS |

| 2000 | 59 | 28 | BSAS |

| 2001 | 52 | 31 | BSAS |

| 2002 | 56 | 29 | BSAS |

| 2003 | 59 | 28 | BSAS |

| 2004 | 53 | 29 | BSAS |

| 2005 | 59 | 28 | BSAS |

| 2006 | 58 | 28 | BSAS |

| 2007 | 57 | 29 | BSAS |

| 2008 | 60 | 25 | BSAS |

| 2009 | 55 | 30 | BSAS |

| 2010 | 54 | 30 | BSAS |

| 2011 | 56 | 29 | BSAS |

| 2012 | 54 | 30 | BSAS |

| 2013 | 52 | 30 | BSAS |

| 2014 | 49 | 35 | BSAS |

| 2019 | 40 | 36 | YouGov |

More details:

- The OSC and INRA polls are quoted by Erskine (1970).

- The IPSOS polls I found somewhere and, uhhh, lost the source and can’t find it anymore. I’ll dig it up if enough people harass me.

- The BSAS numbers are from the British Social Attitudes survey. Despite being funded by charity and the government they don’t publish their actual data, so I estimated the numbers manually from this low quality fiure. They should be accurate to within a point or two.