Capital punishment was debated during the French revolution (1789-1799). Due to the influence of Beccaria and Voltaire, the discussion was similar to how the death penalty is discussed today. Robespierre said “The state’s execution of the death penalty is legalized murder.” (Though as Hammel points out, “given his later role in the Terror, one has to wonder about Robespierre’s sincerity”.)

While the death penalty was not eliminated, they did decide a more humane method was needed. This led to the guillotine, which France continued to use until abolition in 1981.

In the mid-1800s, the Radical movement started to form in France, the goals of which were broadly to realize the original enlightenment values of the French revolution. The Radical party was formed in 1901 and in 1906 Armand Fallières became president. Fallières was a committed abolitionist and for several years he commuted all death sentences. This was controversial, as many felt it trampled on the rights of jurys, citizen bodies that had assisted French judges in decisions and sentencing since the Napoleonic era. There was a debate in 1908, which abolitionists lost, in part due to a perception that public opinion was in favor of retention.

In 1939, the behavior of the crowd at the public execution of Eugen Weidmann caused a scandal, and President Lebrun immediately banned public executions.

During the Vichy regime, judicial executions were fairly rare, something like 50 total. (Of course, this excludes deaths resulting from deporting French Jews and members of the resistance.)

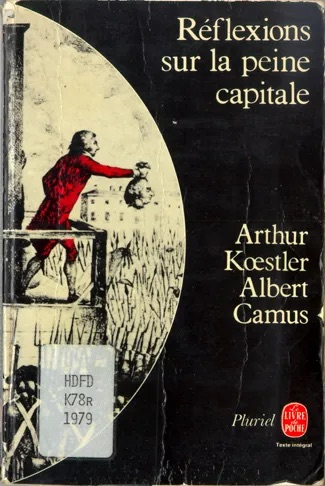

Albert Camus’ 1957 essay Reflections on the Guillotine had a major influence on intellectual thought in France, possibly due to Camus winning the Nobel Prize in the same year. Camus describes how his father, a supporter of the death penalty, saw an execution and was so horrified that after returning home he vomited and spent several days in shock. Many of Camus’ arguments are similar in spirit to those of Beccaria, though he doesn’t agree with everything:

Capital punishment would then be replaced by hard labor—for life in the case of criminals considered irremediable and for a fixed period in the case of the others. To any who feel that such a penalty is harsher than capital punishment we can only express our amazement that they did not suggest, in this case, reserving it for such as Landru and applying capital punishment to minor criminals.

(Camus died in a car accident in 1960.)

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the death penalty was used less and less in France. This was largely because French presidents had the power to commute death sentences. De Gaulle used this power aggressively, and later presidents were very aggressive, with only six during the presidencies of Poher, Pompidou, and Giscard d’Estaing. Executions typically happened only for the murder of a child with sexual overtones, and when guilt was beyond all doubt. Unlike other places, there were no incidents in France with sympathetic or possibly innocent people being executed. This might have kept abolition out of the public consciousness.

In 1972, two prisoners attempted to escape from Clairvaux prison, during which a guard and a nurse were killed. While one prisoner (Claude Buffet) took full credit for both killings, the other prisoner (Roger Bontems) was also sentenced to death. Bontems’ lawyer, Robert Badinter, was outraged that someone was executed even though he had never killed anyone. Badinter dedicated himself to abolition. Throughout the 1970s, he eloquently defended many criminals where the prosecutor had sought the death penalty, often winning life sentences instead.

However, public opinion seemed to move against abolition. There were a series of brutal crimes in France in the 1970s, covered in great detail in the press. The most notorious was Patrick Henry, an ordinary-looking computer programmer who in 1976 kidnapped 8-year old Philippe Bertrand for ransom money. While the case was being investigated, Henry gave an interview in which he said that he hoped that kidnapper would be executed. When he realized there was too much publicity for him to get a ransom, he strangled the girl.

Badinter was hesitant to defend Henry, as he showed no remorse. Still, he ultimately decided to take the case on the theory that if he could win life in prison for this most detestable of murderers, it would prove that the death penalty was never necessary. He was able to elicit ambiguous statements from psychiatrists and, after a beautiful speech, the jury chose life in prison. (Henry was paroled in 2001, returned to prison in 2003 for drug smuggling, and was released again in 2017 a few months before his death.)

The outcome of the Henry trial in 1977 was met with outrage, and Badinter began to feel that a grass-roots movement for abolition could not succeed.

There was another concerning development for abolitionists. Previously, jurys were selected from lists made by municipal authorities, who tended to select more educated people. But in 1978, the French code was modified so that these were drawn uniformly from the population. While many people like Badinter welcomed the democratic spirit of this move, they also realized that this was likely to lead to more executions.

While the public wasn’t changing, elite opinion was swinging strongly towards abolition. There were numerous reports from judges’ unions and various law-reform committees that all suggested abolition. These pushed the issue forward and eventually forced all the major parties to take positions. Ultimately, the leftist parties lined up clearly in favor of abolition, while the rightist parties were divided. Activists like Badinter had been able to make abolition a key part of the left’s profile.

In the late 1970s, the center-right government of President Giscard become unpopular due to a perceived inability to deal with the choc pétrolier caused by the 1979 drop in oil production. It became clear that the leftist parties were likely to win government.

Before the 1981 elections, Badinter approached François Mitterrand and asked him to make abolition an official position of the Socialist party. The logic was that two-thirds of the population supported the death penalty, and a change could only be seen as legitimate if it was promised before the election. The two were already close as a result of Badinter supporting Mitterrand’s 1974 bid for the presidency. During an interview, Mitterrand said, “In my innermost conscience, like the churches […] and international humanitarian associations, in my heart of hearts, I am opposed to the death penalty”.

Mitterrand won the 1981 election on May 10 after which, in the June legislative elections, the leftist parties won huge majorities. Mitterrand eventually named Badinter Justice Minister. He reasoned that speed was of the essence, since French jurys were handing out ever-larger numbers of death sentences, and the unity of the left wasn’t going to hold forever. Badinter presented abolition alone as a single bill, which was quickly scheduled for debate on September 17.

Badinter knew the public was likely to be outraged at abolition. Nevertheless in the debate, he framed the bill as the next step of human progress, a step that a great nation like France should be ashamed not to have taken yet. The bill passed 363 to 117.

Some have portrayed Mitterrand as an unprincipled opportunist, because as justice minister during the Algerian War he had ordered the executions of 45 people. While it’s certainly true that he changed his position, it’s important to remember that the “opportunity” was only with other elites—the public still clearly supported the death penalty and Mitterand knew it.

To make it harder to move backward, in April 1983, France signed Protocol 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights, making it a matter of treaty. The French constitution states that treaties supersede acts of Parliament.

The Conseil Constitutionnel met to decide if this was constitutional. In Décision n° 85-188 DC du 22 mai 1985, they said they saw no problem.

Above is the entire decision—I show this mostly to demonstrate how absurdly laconic the Conseil is compared to the U.S. Supreme Court, which would no doubt produce three contradictory opinions each running hundreds of pages.

Anyway, once Protocol 6 was approved, reinstating the death penalty would require leaving that treaty, which would damage France’s international credibility. In addition, by the terms of the treaty, it would take a minimum of five years to withdraw before the death penalty would resume.

In 2007, the French constitution was modified by a vote of 828 to 26 to add Article 66-1 the entirety of which is:

« Nul ne peut être condamné à la peine de mort. »

(“No one can be condemned to the pain of death.”)

France’s final execution was in 1977, the last execution in Western Europe, and the last use of the guillotine by any government in the world.

Summary: During the 1970s, leftist elites settled on abolition despite popular opinion being to the contrary. Leading up to the 1981 elections, the left realized they were in the strongest position in a generation. François Mitterrand clearly signaled that he intended to abolish the death penalty, won the election, and then did what he had promised. To make this move harder to reverse, France signed international treaties that supersede national law. Over the next 20 years, popular support dropped to around even, though it may have slightly increased in recent years.

What to think of this? The overall story is fairly similar to that in Germany and the U.K.: leftist elites unified behind abolition, conservatives elites were divided, and popular sentiment against abolition wasn’t particularly important. Still, personally, I can’t escape the feeling that France’s path to abolition is somehow a bit more honorable—probably that’s exactly what Badinter intended when he urged that abolition be a clear position before the 1981 elections.

Next up, we’ll look at the history in the U.S. and try to understand why all this didn’t happen there. Then we’ll finally tackle our primary question of how abolition interacts with public opinion.

The death penalty as a lens on democracy

- Introduction

- How Germany banned the death penalty

- How the United Kingdom banned the death penalty

- How France banned the death penalty

- How the United States didn’t ban the death penalty

- Which way the arrows? (soon)

Data and sources

Again, in all these histories of European countries, I rely heavily on Andrew Hammel’s fantastic and underrated book, Ending the Death Penalty: The European Experience in Global Perspective.

Anyway, here are the poll numbers in the plot above. Where possible, I converted to a single “support” score by removing respondents who gave “no opinion”. However, if only “support” numbers are given, I used those unchanged. In the IPSOS polls below, I can’t determine if there was a “no opinion” option. (Let me know if you can figure that out.)

| year | support | oppose | source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1908 | 77 | ?? | IFOP |

| 1960 | 50 | 39 | IFOP |

| 1967 | 51 | 42 | IFOP |

| 1972 | 63 | 27 | IFOP |

| 1979 | 58 | 31 | TNS |

| 1980 | 55 | 37 | TNS |

| 1981 | 58 | 34 | TNS |

| 1982 | 62 | 33 | TNS |

| 1983 | 50 | 38 | TNS |

| 1984 | 56 | 36 | TNS |

| 1985 | 64 | 32 | TNS |

| 1987 | 65 | 29 | TNS |

| 1991 | 61 | 35 | TNS |

| 1993 | 61 | 33 | TNS |

| 1994 | 59 | 36 | TNS |

| 1999 | 46 | 48 | TNS |

| 2001 | 44 | 49 | TNS |

| 2002 | 40 | 54 | TNS |

| 2006 | 42 | 52 | TNS |

| 2007 | 45 | 52 | IPSOS |

| 2014 | 45 | ?? | IPSOS |

| 2015 | 52 | ?? | IPSOS |

| 2016 | 48 | ?? | IPSOS |

| 2017 | 49 | ?? | IPSOS |

| 2018 | 51 | ?? | IPSOS |

| 2019 | 44 | ?? | IPSOS |

| 2020 | 55 | ?? | IPSOS |

| 2021 | 50 | ?? | IPSOS |

More details:

- The 1908, 1960 and 1972 IFOP polls are quoted on Wikipedia.

- The 1967 IFOP poll is quoted by Erskine (1970).

- The TNS polls are quoted by Hammel.

- The IPSOS polls are here on p. 32.