Who is really in charge? In democracies, policies are correlated with public opinion, but why? The obvious explanation is that people choose representatives, and those representatives give them what they want. But maybe the causal arrow points in the other direction—maybe elites choose policies, and the public gradually figures that since that’s how things are, it must be right.

To get some perspective on this question, I looked for an issue to use as a case study. The ideal issue would have divergence between elite and public opinion, plus have a long history in different countries, so we can see how things played out under different conditions.

The best fit I could find is the death penalty. It’s perfect in terms of having a long history, good records, and being prominent enough that the public has an opinion. The primary disadvantage is that it’s, you know, a massive bummer.

So, here’s our goal: Around the world today, the death penalty is less popular in countries where it is banned. But which caused which?

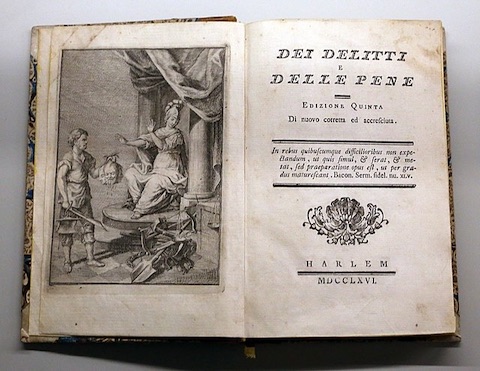

Cesare Beccaria

The movement to abolish the death penalty arguably began in the West in 1764. This is when, at the age of 26, Cesare Beccaria anonymously published On Crimes and Punishments, a call for applying enlightenment values to criminal law. He argues poetically for a break with history:

If it is objected that almost all times and almost all places have used the death penalty for some crimes, I reply that the objection collapses before the truth, against which there is no appeal, that the history of mankind gives the impression of a vast sea of errors, among which a few confused truths float at great distances from each other. Human sacrifices were common to almost all nations; but who would dare to justify them? That only a few societies have given up inflicting the death penalty, and only for a brief time, is actually favourable to my argument, because it is what one would expect to be the career of the great truths, which last but a flash compared with the long and dark night which engulfs mankind.

He suggests that punishments should be set at the lowest level so that a rational person would lose more from the punishment than they gain from the crime. Moreover, he claims a life of hard labor exceeds any potential gain, and is even more of a deterrent than execution since it avoids the spectacle and leaves the person around to serve as a reminder of what happens if you misbehave.

This book had a huge and immediate influence. Voltaire published an—also anonymous—positive commentary that spread the book’s fame as far as America where it was discussed by John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. (Jefferson was partly influenced by a different argument in the book against gun control.) On Crimes and Punishments was also quickly banned by the Venetian and Roman Inquisitions.

Beccaria’s writing is clear, urgent, and seems to speak across time. He sort of resembles an earlier but more influential Peter Singer, another philosopher who was able to shape public opinion.

Anyway, while this all sounds very idealistic, here’s the very next passage:

The voice of a philosopher is too weak against the uproar and the shouting of those who are guided by blind habit. But what I say will find an echo in the hearts of the few wise men who are scattered across the face of the earth. […]

How happy humanity would be if laws were being decreed for the first time, now that we see seated on the thrones of Europe benevolent monarchs, inspirers of the virtues of peace, of the sciences, of the arts, fathers of their people, crowned citizens. […] That is a reason for enlightened citizens to wish all the more fervently for their authority to continue to increase.

Put less politely:

- While the death penalty is wrong, the teeming masses will never understand why.

- But thankfully Great Leaders are in charge, not the public.

- In fact, this shows exactly why monarchies are so important—let’s make monarchies even more powerful!

This is less comfortable for someone sitting in a democracy a few centuries later.

Now, this might just be some pragmatic flattery, and anyway I don’t judge monarchists so far in the past. But whatever the motivations, look at what Beccaria is suggesting: We need an elite—monarchs are certainly elite—to impose enlightened policies on the public. In fact, this happened. Tuscany, Russia, and Austria had monarchs who banned capital punishment soon after this book came out (though the bans didn’t last forever).

But that’s not our story. We’re interested in the history of the death penalty in democracies, which happens much later. In the next few posts, we’ll go over the history of the death penalty in Germany, the UK, and France, which abolished the capital punishment in 1949, 1969, and 1981. We’ll then contrast this to the U.S., where it remains in use. Our focus is not if the death penalty is good or right, but how these policies came to be, and what the public thought about them over time.

Now, why is it worth going through all this history?

You probably know that the U.S today is the only Western democracy that maintains the death penalty. (See also: Belarus, Belize, Japan, Taiwan.) But did you know the following?

- When Germany, the U.K., and France banned the death penalty, they did so despite the opposition of 2/3 of their populations?

- For much of the 1960s, public support for the death penalty in the U.S. was lower than in these other countries, despite the U.S. having an order of magnitude higher levels of violent crime?

- In the U.K. and France, something like half of the population still supports the death penalty today, only slightly less than in the U.S.?

It’s not obvious that the U.S. is the country that needs explaining here! If your model of the world is that the death penalty is bad and democracies stop doing bad things, then sure, the U.S. is puzzling. But if your model is that democracies do what people want, then how did so many countries implement policies that were against the will of their citizens?

The death penalty as a lens on democracy

- Introduction

- How Germany banned the death penalty

- How the United Kingdom banned the death penalty

- How France banned the death penalty

- How the United States didn’t ban the death penalty

- Which way the arrows? (soon)