(Or: Things where there’s a case worth considering that they don’t work all that well for most people.)

-

Acupuncture. (link)

-

Phenylephrine. (link)

-

Multivitamins. (link)

-

Phosphoric acid. (for nausea; link)

-

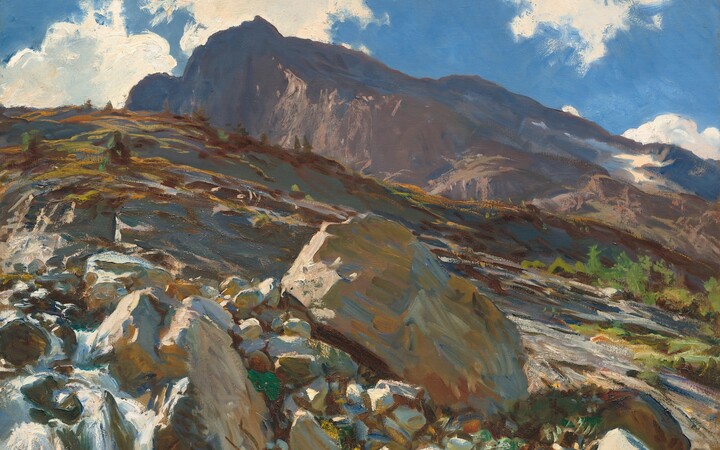

Tree-based knowledge organization. The physical world whispers to us to organize information into “trees”. For example, say you write something on a piece of paper, put the paper into a binder, put the binder into a box, put the box into a closet:

OK. But on my computer, I have some folders that look sort of like this:

(You’re reading “A”) The problem is, most projects end up needing some writing. And writing often needs some “projecting” like making plots. And sometimes I don’t get paid for stuff I thought I would and usually projects bleed into each other and sometimes I split something I was writing into pieces and I neglect the last piece and it remains in limbo for years. Every level of the hierarchy feels forced and artificial. Maybe there’s a better way, but my guess is that life is just too messy.

-

Graph-based knowledge organization. If trees are too rigid, why not graphs? Wikis and Zettelkasten systems let you organize information into “nodes” of content that you can link to each other however you want. Some people love these. But I reckon that of those who try them—already a select group—95% quit within a month. I suspect the reason is partly that more flexibility means more decisions and partly that flexibility is a curse as well as a blessing—it allows you to better represent the messy world, yes, but it also makes your representation less predictable and legible.

-

Elegant mathematical notation. Why write matrix multiplication as Aij = Σk BikCkj with all the ugly indices when you can just write A=BC? Well, what if you wanted to write Xnij = yn Σk BnikCnkj?

-

Doing math via symbol manipulation. Say you’re trying to prove something. If moving symbols around on the page using some symbol manipulation rules you’ve memorized doesn’t give you the answer within an hour or two, you may have to resort to thinking.

-

AI methods that don’t leverage computation. (link)

-

Expecting people to follow written instructions. Sufficiently motivated people will climb any mountain and walk over any length of broken glass. But in most situations, if you send most people written instructions, they simply will not follow them and quite possibly will not even read them. This is true even when instructions are simple and stakes are high, like taking medication.

I’m not sure why this is true, but it explains the age-old question of, “Why did we have this meeting when it could have been an email?” And if you can follow moderately complicated instructions, that’s almost a minor super-power.

-

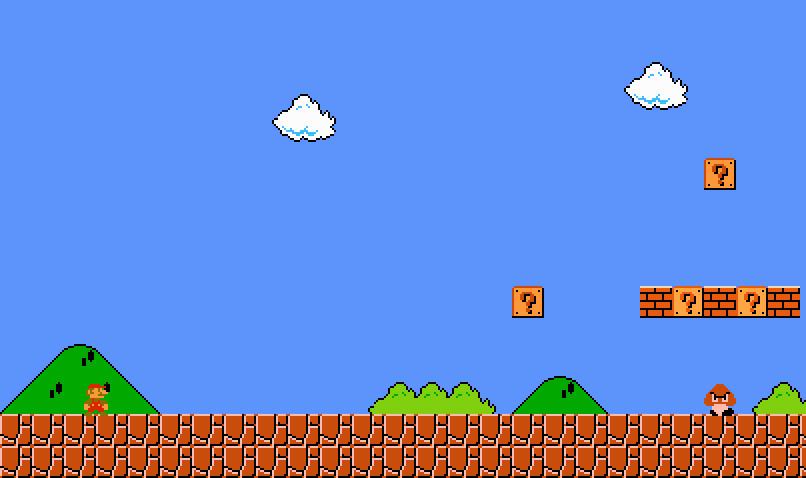

Tearing your hair out because people don’t follow written instructions. You can fill your instructions with BOLD CAPS and rend your garments when this too fails. A more pleasant option is to craft supportive interfaces where people don’t need instructions. I’m convinced the best interface in history is the beginning of Super Mario Brothers. You just start.

When I first made my MBTI test I had a paragraph of instructions at the top. I never liked how it looked so I kept making it shorter. After 10 revisions I was left with something like “please answer these questions” which I just deleted.

-

Explaining board games. Here’s how people usually seem to teach board games:

- Someone spends 5-30 agonizing minutes explaining how the game works.

- No one understands anything.

- The game starts.

- As each game mechanic arises, people ask, “Hold on, how does this work?”

You can skip to step 3.

-

Jokes. Probably less than 1 in 10 people can tell jokes with punchlines. But lots of people can tell funny stories.

-

Fixing relationship problems by having a baby.

-

Pulling Out. (link)

-

Telling people something they think is obvious is actually surprising. If you’d like to fail to convince people that something is non-obvious, here are some of my favorites: (1) that the world is made out of atoms, (2) that sexual reproduction is based on two sexes rather than three, (3) why there are seasons, (4) where the atoms in trees come from, (5) that 80 years after their invention nuclear weapons would remain really hard to make.

-

Arguing with people. Say Alice strongly believes X. You give devastating evidence that X is in false. How often will Alice turn around and say, “You’re right, I’m wrong, X is wrong.”?

Words do not exist that will make people do that. (Aside from a few weirdos who’ve intentionally cultivated the habit.) But if you make a good case and leave her some room for retreat, you may find that Alice’s position is a bit softer the next time X comes up in conversation.

-

Subsidizing undesired behavior. Say you’re waiting at a busy intersection and someone walks between the lanes of cars asking for money, putting themselves at risk and blocking traffic for a bit after the light turns green. If you give them money, it’s unlikely this will convince them they should stop doing this.

-

Doing unto others as you would have them do unto you. This is a beautiful idea, but often other people simply don’t have the same needs you do.

-

Making sense of interactions with crazy people.

-

Wanting to be liked.

-

Getting closure with your parents for how you were treated as a child.

-

Thinking about your life like a movie. Most good lives don’t have compelling plots and almost all of them have bad endings.

-

Saying the right thing. When someone you care about is in crisis, you may not know what to say. But don’t let that stop you. You don’t have to find the right words. No one expects you to. Probably they don’t exist.

-

Warby Parker Multiverse. (Apparently)

-

Communism.

-

Picking stocks. You don’t just have to beat the market, you also have to beat all the extra taxes you pay for trading more. You may ask—what about hedge funds? Don’t they beat the market? Sure, but think about where their margin comes from.

-

Counting calories. Say your weight is stable and you start eating a single extra piece of sandwich bread every day. After a year, you’ll gain 3.8 kg (8.3 lb) of fat. Almost no one counts calories that accurately.

-

Dieting. In some sense, dieting works great. As far as I can tell, you can lose weight by following any diet, be it carnivore, vegan, Mediterranean, low-fat, low-carb, low-protein, potato, grapefruit, or baby food. The simplest explanation is that you eat less when you have fewer food options. But when you go back to having lots of options, you eat more again and gain all the weight back. The only way to lose weight permanently is to permanently change your food environment. Or, you know, drugs.

-

Nonfiction books. Arguably? How much do we really retain?

-

Waiting. Most people in history never had any forks in their road. “Following your dreams” was such an alien concept that it wouldn’t occur to anyone to be upset for not being able to do it. I suspect this wasn’t all that bad. (Sea otter dreams range from “eat some good gastropods” to “eat some good echinoderms” and they sure look happy.) That said, if you really want to do something, don’t wait for some unspecified time when it’s more convenient and then watch that time recede before you.

-

Quality over quantity. I often worry that I write too much on this blog. After all, the world has a lot of text. Does it need more? Shouldn’t I pick some small number of essays and really perfect them?

Arguably, no. You’ve perhaps heard of the pottery class where students graded on quantity produced more quality than those graded on quality. (It was actually a photography class.) For scientists, the best predictor of having a highly cited paper is just writing lots of papers. As I write these words, I have no idea if any of this is good and I try not to think about it.

-

Solving supply shortages with consumption subsidies. Say rent is expensive and the government gives everyone a $500/month rent voucher. What happens? Well, why is rent expensive? If people really want to live somewhere, they keep bidding with each other until the price hurts enough that some give up and live elsewhere. The subsidy shifts the “hurt curve” $500 to the right. Unless it’s possible to make new buildings, most of the money will just end up in the pockets of landlords.

-

Religion without the G word. (link)

-

Rewriting your code from scratch. Your code is a horror, but if you start over maybe you can avoid all the mistakes. Many claim this is a fantasy—you’ll just make new mistakes and create a different kind of horror. Better to just improve what you have.

-

Trying to figure it all out ahead of time. For hard problems, you can sit around trying to see around all corners and anticipate all possibilities. This can work—when Apollo 11 landed on the moon, everything worked the first time. But it’s really hard. If you can, it’s easier to build a prototype, learn from the flaws, and then build another one. (This, of course, contradicts the previous point.)

-

Algorithmic ranking. Arguably?

-

Chimpanzees as pets.

-

Controlling for a variable. (link)

-

Controlling for a variable. (link)

-

Controlling for a variable. (link)

-

Controlling for a variable. (link)

-

Controlling for a variable. (link)

Things that work: Dogs, vegetables, index funds, jogging, sleep, lists, learning to cook, drinking less alcohol, surrounding yourself with people you trust and admire.