Sam Quinones was recently on Econtalk and in the Atlantic talking about methamphetamines and homelessness. He points out that “old” meth was made from ephedrine and that “new” meth is made from a chemical called Phenylacetone or P2P. He suggests that new meth might be chemically different in a way that caused people to go crazy, starting around 2017:

Ephedrine meth was like a party drug. […] You could normally kind of more or less hang onto your life. You had a house, you had a job. […] P2P meth was nothing like that. It was a very sinister drug. It brought you inside. You didn’t want to be around other people. You wanted to just kind of be alone with whatever bizarre thoughts your mind was now cooking up, and conspiracies.

I was curious about this. What do we know about the difference between old meth and P2P meth? What evidence is there that these have a chemical difference?

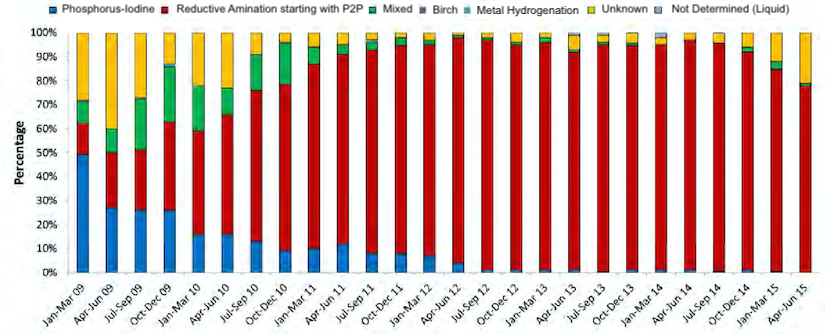

Meth in the US shifted to P2P synthesis between 2009 and 2012.

In the before times, meth was made with ephedrine or pseudoephedrine. However, in 2006, the US banned over-the-counter sales of pseudoephedrine, and in 2008 Mexico banned almost all sales. In response to this, meth makers switched to a synthesis based on P2P, which can be made from many different, widely available, source chemicals.

The Drug Enforcement Agency tests the meth they seize to see how it was made. Here’s their data starting in 2009, where you can see that P2P synthesis (in red) rapidly displaces the older ephedrine-based synthesis (in blue).

How could P2P meth be different? There are two ways: Either it could be a different type of meth, or the meth could be contaminated with some other chemicals.

Let’s talk about different types of meth first.

Isomers

A naive P2P synthesis would produce an even mixture of l-meth and d-meth.

For many complex molecules, you can take the atoms, and “flip” them to get another stable version of the same molecule, called an isomer or (more specifically) an enantiomer. These different versions of the molecule can have very different effects on the body.

Methamphetamine happens to be one of those molecules. The one that produces the effects we call “meth” is d-methamphetamine (d-meth). That’s the one that increases dopamine in the brain, causing euphoria. (It’s also the one that is sold at pharmacies in the US to treat ADHD and obesity.) On the other hand, l-methamphetamine (l-meth) has no effects on dopamine and presumably isn’t nearly as much fun.

Anyway, a synthesis that turns P2P into meth will create an equal mixture of d-meth and l-meth, basically because atoms bouncing around randomly are equally likely to end up in either of two equally low-energy configurations. Older synthesis methods using ephedrine would create only d-meth.

P2P initially had a fair amount of l-meth, but it was almost all gone by 2019.

Here’s data from the DEA again, where “potency” is the percentage of d-meth among all meth. This data is assembled from the National Drug Threat reports from many different years:

Be careful here: Take a sample of meth that’s ¼ d-meth, ¼ l-meth, and ½ other impurities. This would count as 50% potent because 50% of the meth is d-meth. (Other impurities are accounted for with “purity” below.)

The dip in 2014 might be explained by the introduction of a new synthesis method (NTS), which we’ll talk about below.

Unfortunately, I can’t seem to find any data going back further to before when P2P meth was introduced. It’s likely that d-meth was higher before P2P synthesis become popular, though this paper analyzes meth in Australia and finds that, for some reason, ephedrine-based meth often has fair amounts of l-meth, too.

L-meth is in various easy-to-obtain drugs.

Vick’s VapoInhalers contain 50mg of l-meth, which they spell in an unusual way probably to reduce the number of people who notice what’s in there and freak out.

L-meth is also produced as a metabolite of Selegiline, a drug for Parkinson’s and depression.

Contaminants

The purity of meth is now higher than ever.

The DEA has tracked purity in meth that they have seized for a long time. They define purity to be the percentage of meth (d or l) amongst all chemicals in the sample. Here’s a plot of all the data I could find:

Now, the terms “purity” and “potency” as used by the DEA are a bit confusing. A consumer of meth probably cares about the percentage of d-meth amongst all chemicals in the sample. You get this by multiplying the purity and potency:

Modern street meth is higher quality than ever, around 95% d-meth on average.

There are many ways to make P2P meth.

Here’s a figure that shows how P2P might be produced from source chemicals, simplified from this paper:

This shows two routes to make P2P. The top route uses benzaldehyde and nitroethane to produce nitrostyrene (NTS), which is then made into P2P. The bottom route uses ethyl phenylacetate (EtPA) to make phenylacetic acid (PAA), which is again made into P2P. Note that lead acetate (which has been raised as a concern) is only used in the PAA synthesis route.

Synthesis methods for P2P meth have changed repeatedly.

This paper by DEA scientists goes over the profiling of different types of P2P meth. Here’s the history, as far as I can make out:

- Starting around 2009, people used EtPA to make PAA.

- Around 2014, there was a shift towards using the NTS synthesis.

- Around 2018, there was a shift back towards using PAA. (It’s not clear if this PAA was sourced directly, or made from EtPA or what.)

It’s much messier than this implies: The transitions were gradual, and the DEA finds a fair number of “unknown” samples each year that they can’t classify.

On top of these different methods to make P2P, there are different methods to convert P2P into meth, and these have probably changed over time as well. The DEA seems to attribute most impurities to the P2P production step. However, they seem more interested in the meth supply chain than how impurities might affect the health of users.

This history of synthesis methods does not support the theory that lead acetate in meth is causing schizophrenia: Lead acetate was used much less between 2014 and 2018 when NTS synthesis mostly displaced PAA synthesis. This doesn’t correlate with reports of schizophrenia at all.

Quantity

How much meth is used, by how many people? It’s hard to say exactly, given that we’re talking about a black-market supply chain and a product that’s illegal to consume. Still, we have various windows into things.

The amount of meth seized at the border is skyrocketing.

Here’s a figure, modified from the UN’s 2021 World Drug Report.

To some degree, this reflects Mexican-made meth displacing US-made meth, but this isn’t a major factor: Already in 2012, the DEA estimated that 80% of meth in the US was Mexican-made.

Sewage measurements suggest a doubling of usage in Seattle around 2017.

There’s an impressive project in Europe to measure drug use from biomarkers in sewage. They invite participation from cities around the world, which Seattle does. Here are their measurements (extracted from measurements in the 2020 report):

In 2016, Seattle already had the highest levels of any participating city in the world, but these doubled in 2017 and then stayed roughly constant after.

More people now report using meth, especially using a lot of meth.

One way to estimate how much meth people use is to ask them. The US Department of Health and Human Services maintains the Substance Abuse & Mental Health Data Archive with data going back to 2002. I used this data to get two numbers: The percentage of people who used meth at all in the past 30 days, and the percentage of people who used meth every day in the last 30 days. (The latter is only available since 2015). These are proxies for the number of casual users and the number of serious addicts.

The number of people who use meth has increased. However, the real growth is in the number of heavy users, which tripled just between 2015 and 2019.

Here are some details on the data used in the above graph, in case you'd like to play around with similar analyses.

These are the raw cross-tables:

After following one of those links, turn off all table display options except for row %, then click the “Run Crosstab” button.

Meth prices have come down.

If supply is increasing, we would expect prices to come down. Have they? The DEA tracks prices in seized meth going back at least as far as 2005. After cobbling together (sometimes contradictory) numbers on National Drug Threat Assessments, here’s the best series I could find:

The DEA continued to track prices after 2017, but they noticed that lots of researchers found this data useful and therefore stopped publishing it because screw you.

I’m not sure how reliable these numbers are. They vary a lot based on the quantity being bought and the location in the country. The RAND corporation estimates numbers that are 2-3x higher overall, but show a similar relative decrease from 2008 to 2016.

There are also random quotes scattered across the media: The Kansas Bureau of investigations (2017, 2018, 2019, 2020) reports the price of a pound of meth dropping from around $15k in 2014 to around $4k in 2019, and slightly rebounding to $5k in 2020 during the pandemic. (Apparently, the meth supply chain is more robust than that for semiconductors.) A public television station in California in 2019 quotes a law enforcement officer in Fresno as saying a pound of meth had dropped from $6k for a pound a few years before to only $1k per pound now.

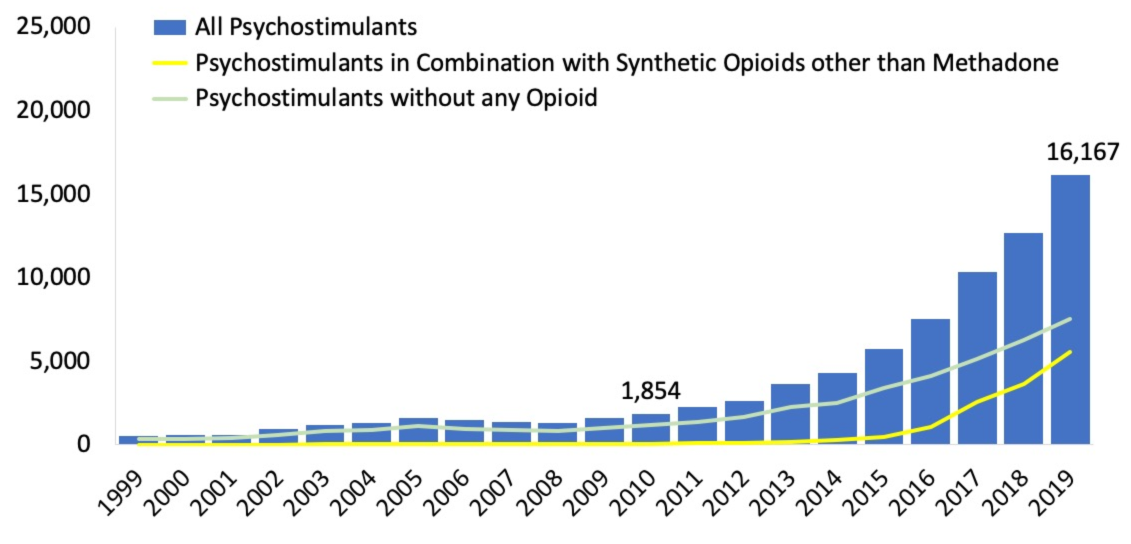

Meth overdoses are skyrocketing.

From the National Institute on Drug Abuse, here are the number of overdose deaths per year. This includes other psychostimulants like caffeine and MDMA, but the deaths overwhelmingly come from meth:

This isn’t slowing down. More recent data (not plotted) indicates that that 2020 had 24,076 deaths, and things sped up even more during early 2021. While a lot of these deaths come in combination with opiates like Fentanyl, a lot don’t, too.

We can put these numbers in context with some very rough arithmetic.

Let’s compare to someone who takes amphetamines/Adderall for ADHD, typically prescribed 5-20 mg per dose. Meanwhile, a strong single dose of meth is 40-150 mg, on top of which people say that meth is around 2× as potent as amphetamines. So meth users take roughly 15× as much per dose as the typical Adderall user. Meth addicts often dose several times per day, due to the short half-life, meaning a total of 300-800 mg per day.

That’s a lot, but let’s talk about overdoses. It’s actually pretty hard to overdose on meth. One way to estimate it is to look at animals This paper says that 50% of rats and mice die at a dosage of around 55 mg/kg. This suggests that an 80 kg (175 lb) person would need to take 4400 mg of meth to have a 50% chance of dying. Now, it’s not safe to extrapolate numbers between animals and humans, and there’s a blurry boundary between lethal and non-lethal doses. But there are many reports out there of people taking 500 mg of meth at a time without overdosing. That’s something like 100× a clinical dose of 10mg of Adderall.

That’s an insane amount of stimulants. I find it difficult to understand how anyone would want to do that to themselves. But they do, enough that meth overdoses kill half as many people as die in car accidents, and the numbers are still increasing. I guess drug users use a lot of drugs.

Takeaways

What to make of all this?

First, I think it’s unlikely that l-meth is causing people to go crazy. Modern P2P meth is nearly pure d-meth, and the percentage of l-meth peaked before 2011, before these reports of schizophrenia.

Second, the evidence we have is against the idea of contaminants in P2P meth. Almost all meth was produced using P2P since 2012, before most reports of schizophrenia. And P2P meth synthesis has changed several times in the interim, resulting in higher purity than ever before.

Third, the major impact of P2P synthesis is that a lot more meth is available. We have many sources of evidence for this: Border seizures, sewage measurements, usage surveys, prices, and overdose data. All these indicate that people are using historically large amounts.

Does this rule out the idea of contaminants? No. Even if it’s 97% pure d-meth, there could be something very nasty lurking in that last 3%. But I don’t see the need for such an explanation. We know there are many more heavy users, so there’s no need to go beyond the idea that quantity has a quality all its own.