Claim: Per kilometer driven down the road, electric cars create more particulate air pollution than gas cars. That’s ignoring all other emissions and anything that happens at a power plant or during manufacturing.

Sounds odd, but the argument is pretty simple:

- Modern gas engines are so clean that exhaust is negligible compared to brakes, tires, and road dust.

- Heavier cars create more of that stuff.

- Batteries are heavy.

(You can get some version of this argument in The Atlantic, The Washington Post, The Guardian, or by asking my dad.)

That can’t be right, can it?

Conservation of mass

Let’s start with a sanity check. Is it crazy to worry about air pollution from brakes or tires?

First, how much do cars emit through exhaust? After 30 minutes with US regulations, I learned only that those regulations are very confusing and I hate them. But many (mostly coastal) states follow California’s more stringent rules. These are simple: A car’s exhaust can put at most 1.9 mg of particulate matter into the air for each kilometer driven down. EU rules are slightly looser at 4.5 mg/km.

Could brakes come close to that? Well, depending on the vehicle, disc brake pads have 100 to 400g of friction material. Perhaps 80% of that material is worn away before replacement, which happens after something like 65,000 km. Assuming 200 g of friction material, that suggests an average of

4 brakes × 200 (g/brake) × 0.8 / (65000 km) = 9.8 mg/km

of material lost from brakes. That’s more than California or EU exhaust limits. So it’s at least physically possible that brakes could make more particulate pollution.

What about tires? They weigh around 10 kg. By the time tires are replaced, around 10% of that mass is lost. This happens after 80,000 km or so. That suggests an average of

4 tires × 10 (kg/tire) × 0.1 / (80000 km) = 50 mg/km

of mass lost from tires. Again, that’s more than exhaust rules allow. Our theory survives first contact with reality.

Airborne material

But… not all material that’s lost becomes airborne. And not everything that goes airborne will be the small particles that hang around in the air the longest and do the most damage to health.

After reading the literature, my best guess is that around 50% of brake material becomes airborne, 40% becomes particles smaller than 10 microns (PM₁₀), and perhaps 15% becomes particles smaller than 2.5 microns (PM₂.₅). For tires, estimates are all over the place, but perhaps 1 to 10% becomes PM₁₀.

To measure small particles, we typically consider only those smaller than 10 microns (“PM₁₀”) or 2.5 microns (“PM₂.₅”). They are still measured in grams, just after screening out larger particles.

So how much of brake/tire emissions end up as these small particles? Here’s a review based on Grigoratos and Martini.

For brakes, something like 50% of mass goes airborne, and most of that is smaller than 10 microns. Papers disagree about how much qualifies as PM₂.₅. My best guess is that 40% of brake mass ends up as PM₁₀ and perhaps 15% as PM₂.₅.

For tires, most mass does not become airborne, but instead becomes large particles that either get stuck in the road or fall nearby. But people give hugely varying estimates for how much mass goes airborne, ranging from 0.1% to 10%.

You can get another perspective by taking real air pollution and doing a chemical analysis to figure out how much came from brakes or tires. In some large Chinese cities, Zhang et al. attribute 1-3% of PM₁₀ to brakes and 7-9% to tires. At four sites in California, Jung et al. attributed 9-16% of PM₂.₅ to brakes and 6-13% to tires, as compared to 2-7% for gasoline engines and 4-15% for diesel engines. Lots of older research also seems to agree that tires are a significant contributor. That would be impossible in only 0.1% of lost tire mass when airborne, so I’ll assume that between 1% and 10% of lost tire mass becomes PM₁₀.

Here are some updated calculations using those estimates:

| Brake Wear | Tire Wear | |

|---|---|---|

| Total mass lost | 9.8 mg/km | 50 mg/km |

| Airborne emissions (total) | 4.9 mg/km (50%) | |

| Airborne emissions as PM₁₀ | 3.9 mg/km (40%) | 0.5-5 mg/km (1-10%) |

| Airborne emissions as PM₂.₅ | 1.5 mg/km (15%) |

Various papers have also given direct estimates ranging from 1 to 9 mg/km of PM₁₀ for brakes and 4 to 13 mg/km for tires.

Since they’re so harmful, there are often special rules for small particles. The EU allows only 0.3 mg/km of PM₂.₅. That’s lower than the above estimates.

Chemical analyses of real air pollution in China suggest that brake and tire emissions are significant but much smaller than exhaust. However, similar analyses in California suggest brake and tire emissions are both larger than exhaust.

However you look at it, the evidence suggests that with clean modern gasoline cars, brake and tire emissions really can be larger than exhaust. Our theory is still alive.

Batteries are heavy

Now the claim also assumes that electric cars would produce more brake and tire emissions because they are heavier. Is that true?

First, how do brake and tire emissions increase when a vehicle gets heavier? Do they scale as the fourth power of weight like road damage does? Apparently no—brake and tire emissions just scale linearly: A car that weighs 50% more puts out around 50% more tire and brake emissions (see Aatmeeyata et al. or Simons).

Now, are batteries really that heavy? Yes. A Tesla Model Y battery weighs 770 kg. Compare that to 820 kg for the entirety of a classic Volkswagen Beetle. Most electric cars have smaller batteries, and they can make up some weight by not having transmissions. But still:

| Electric Car | Weight (kg) | Gas Car | Weight (kg) | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tesla Model 3 | 1752 | Toyota Camry | 1515 | 1.16 |

| Tesla Model 3 | 1752 | Honda Accord | 1488 | 1.18 |

| Tesla Model 3 | 1752 | BMW 330i | 1615 | 1.08 |

| Ford F-150 Lightning | 3742 | Ford F-150 | 2935 | 1.28 |

| Ford Mustang Mach-E | 1959 | Ford Mustang | 1692 | 1.16 |

| Tesla Model Y | 2066 | Toyota RAV4 | 1615 | 1.28 |

| Tesla Model Y | 2066 | Honda CR-V | 1601 | 1.29 |

| Kia Nero EV | 1688 | Kia Nero | 1393 | 1.21 |

Timmers and Achten did a similar exercise in 2016 and found slightly higher ratios.

So electric cars are perhaps 20% heavier on average. From that, we’d expect perhaps 20% higher brake and tire emissions. Except…

Regenerative braking is good

Disk brakes use friction to convert kinetic energy into heat. Electric cars have regenerative brakes, where the motor instead converts kinetic energy into electrical energy. They also have disc brakes, but these are only used for rapid stops.

Regenerative brakes are much cleaner than disc brakes. It depends on driving patterns, but different tests have found that electric cars have 60-90% lower brake emissions. A rule of thumb is that electric cars have 66% lower brake emissions than gas cars, despite being heavier.

Where does that leave us?

Take a gas car and a comparable electric car. Our estimates say the electric car will have 100% lower exhaust emissions (because it doesn’t have an engine), 66% lower brake emissions (because it has regenerative brakes), and 20% higher tire emissions (because it is perhaps 20% heavier).

See the problem? Say the gas car emits E from the exhaust, B from the brakes, and T from the tires, then the difference in emissions is

(total gas car emissions) - (total electric car emissions) = E + 0.66 B - 0.2 T.

If that’s going to be a net increase, the tire emissions of the gas car would have to be so high that a 20% increase would outweigh both a 100% decrease in exhaust and a 66% decrease in brakes, i.e. that 0.2 T > E + 0.66 B.

It’s plausible that 0.2 T > E for a car with a modern gas engine. But there’s no reason to think that 0.2 T > 0.66 B. Most likely, the electric vehicle’s regenerative brakes will make up for any extra tire emissions due to the weight. So I don’t see gas cars beating electric cars no matter how clean the engines.

What is plausible is that a hybrid car would have lower emissions than an electric one. They still have regenerative brakes to decrease brake emissions, but they don’t have huge heavy batteries to increase tire emissions.

Emissions Analytics is a consultancy that has pushed the “hybrids are better than electrics for air pollution” narrative very hard. They did an experiment with two SUVs: A Kia Niro hybrid, and a Tesla Model Y electric vehicle. These were their results:

| Kia Niro hybrid | Tesla Model Y | |

|---|---|---|

| Test Weight | 1718 | 2260 |

| Exhaust emissions | 0.000142 mg/km | 0 |

| Tire wear | 43 mg/km | 54 mg/km |

Emissions Analytics seems to be very good at writing press releases and got a ton of attention for this. But let’s note:

- They measured how much mass the tires lost and called this “tire emissions”, even though we know most tire mass does not become airborne. The actual air pollution from the tires is surely much lower than shown above.

- The logical thing would have been to compare the Kia Niro hybrid to a Kia Nero EV. It’s unclear why they compared to a Tesla Model Y instead.

- They found that the Kia’s exhaust emissions were 30,0000× lower than the EU regulatory limit of 4.5 mg/km. I’ve never seen tests from any other organization that found such low values.

But whatever, I still believe the hybrid probably had lower total emissions. The Tesla is 32% heavier and lost 26% more tire mass. The Kia has tiny exhaust emissions, and probably similar (or lower) brake emissions.

So here’s a revised conspiracy theory, which I think the evidence supports:

Per distance driven down the road, an electric car creates less particulate air pollution than a comparable gas car—but more than a comparable state-of-the-art hybrid car.

So what?

One defensible reaction is not to care. We’ve ignored emissions of NO, NO₂, volatile organics, ozone, CO, and CO₂. And we’ve ignored the benefits of having an electrified transportation system. Maybe these are more important than extra tire emissions.

But my reaction is different. Note what we’re comparing: The internal combustion engine is one of the most exhaustively optimized human technologies. We’ve spent decades reducing its particle emissions. Emissions from brakes are tires are unregulated and most people don’t realize they exist. Is it surprising that engines might do better?

I propose: If brake and tire emissions are a problem, how about we directly try to solve that problem?

For one, batteries are not the primary cause of vehicles getting heavier. Passenger vehicles already got around 35% heavier between 1980 to 2022 (eyeballing from Fig 3.6 in this EPA report) even though electric vehicles are still a tiny fraction. If we want to reduce weight, are batteries obviously the place to cut?

We’ll probably eventually get batteries with better energy density and this problem will recede. But in the meantime, could we cope better? Batteries are gigantic because they’re designed to provide something like 400km of range. Most people rarely need all that range, so most of the time, much of the battery is dead weight. Can we make it easier to change battery sizes or swap cars or something?

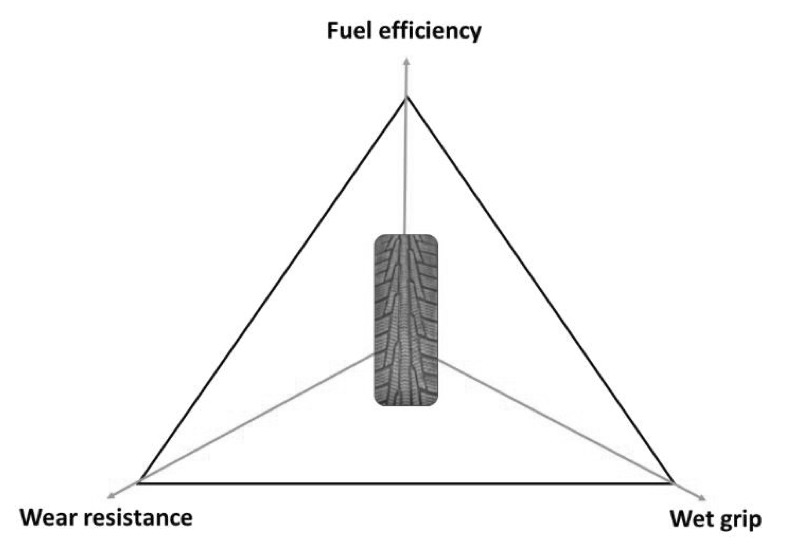

Or, maybe we can design tires to create fewer particles. There’s some reason for pessimism here—in tire engineering, there’s a concept of a “magic triangle” between rolling resistance, slip resistance, and wear resistance. See this visualization from Ydrefors:

You can’t easily reduce wear resistance without harming fuel efficiency or grip. But maybe we can design tires so that they wear at the same rate, but only produce large particles that quickly fall to the ground?

Or, maybe we can make roads better. In the Netherlands, roads are often made out of “very open concrete” or ZOAB (zeer open asfalt beton). This is a material with holes that can supposedly capture up to 95% of all particles generated by tires. The details of this magical technology seem to only be available in Dutch, but it needs to be cleaned a couple of times a year and allows you to do insane things like pour a bucket of water through your road. It’s more expensive, but maybe if the other 99.8% of the world helped out, we could bring down costs.

Or maybe we could do something else. I don’t know! I’m just saying that the problem isn’t heavy batteries per se, but that we haven’t much tried to control tire emissions. If we try, we can probably figure something out. But let’s not pre-judge the solution.

Odds and ends

-

The EU has proposed to regulate tire and brake emissions starting a few years from now.

-

Did you know asbestos is used in brakes? They’re banned in most of the rich world, but not the US. The EPA tried to ban them in 1989 but were overruled by the Supreme Court. Car manufacturers eventually eliminated asbestos anyway, but for now you can still today totally legally buy aftermarket imported brake pads with asbestos and then go grind them up and send the particles out there for other people to breathe. (The EPA proposed a total ban in 2022. Asbestos seemingly remains in use for brake pads in China, Russia, and India, though hypothetically banned in China and India.)

-

If you like conspiracy theories, try this: Evangeliou and Grythe suggested that enough tire and brake particles are floating around in the air and landing in the Arctic that they might change the albedo of the ground and thereby accelerate climate change. This is too good to check, so please don’t check it, I want to believe.