FROM BEING A WASTE TO THE BATHER AND COUNTRY, AND FOR MAKING IT BENEFICIAL TO THE PUBLICK

Europe is in an energy crisis. There are lots of things that might be done, but most are slow or expensive or painful or don’t accomplish much. But here’s a little daydream:

- We use lots of energy to heat our homes.

- We use lots of energy to heat water for showers.

- Most of the heat in that water goes literally down the drain.

- We could scavenge that heat by letting the water sit in the bottom of the shower for a while.

This is fast and free and easy-ish. But is it significant? I get triggered by the phrase “every bit helps”, which somehow manages to turn a tautology into an implied call to forsake reason. The only way to know if this matters is to do the arithmetic.

So I decided to do it. I focused on the UK, because a fair number of UK-ians read this blog and because there’s good data available (in English). I tried to answer two questions:

- What’s the national impact if everyone does this?

- What’s your personal impact if you do this?

National impact

If everyone in the UK let their bathwater heat up their home before throwing it away, what fraction of total UK energy could be saved? Below, I’ll estimate that, in winter:

- 29% of UK energy goes to domestic uses.

- 17.5% of domestic energy goes to heating water.

- 88.2% of the energy that goes into water heaters becomes heat in water.

- 50% of domestic hot water is used for showers and baths.

- 80% of the heat in water survives the trip from the water heater to the shower.

- 90% of the heat in that water currently goes down the drain.

- 75% of that heat is recoverable by letting it cool to room temperature.

If we multiply all these numbers together we get that 1.2% of total UK energy usage could be saved in this way. I also estimated uncertainty ranges for each of the above numbers. When multiplied together these give a range of 0.4% to 3.5%.

In more detail, the math for the regular estimate is

.29 × .175 × .882 × .50 × .80 × .90 × .75 = 0.0121.

The math using all the lower bounds is

.26 × .165 × .845 × .35 × .70 × .75 × .62 = 0.0041,

while the math for the upper bounds is

.32 × .185 × .940 × .80 × .90 × .95 × .92 = 0.0350.

So is 1.2% a lot? That's debatable, but it's probably as large as some of the common suggestions for reducing energy, like turning off the lights when you leave the room, turning off taps properly, or unplugging idle chargers.

Domestic lighting consumes 3.8% of the UK’s energy. If being careful when leaving the room reduced the amount of energy people use by a third, then that would be 1.3% of national energy. The same page suggests that a leaky hot water tap could waste enough hot water to fill half a bath after a week. That’s not huge, and also I suspect that much of the heat that dribbles out of a tap would escape into the air or basin before the water goes down the drain. David MacKay estimated that idle phone chargers consume 0.01% of UK energy.

Personal impact

The second question is: Of all the energy you use to heat water when showering, what fraction could you recover by letting the water accumulate and cool down? This follows from four numbers.

- 88.2% of the energy that goes into water heaters becomes heat in water.

- 80% of the heat in water survives the trip from the water heater to the shower.

- 90% of the heat in that water currently goes down the drain.

- 75% of that heat is recoverable by letting it cool to room temperature.

Combining these suggests that 48% of the energy can be scavenged, with a range of 28% to 74%. So a reasonable heuristic is that letting your shower water heat your home saves as much energy as cutting the length of your shower in half.

The math for the point estimate is

.882 × .80 × .90 × .75 = 0.476.

The math for the lower bound is

.845 × .70 × .75 × .62 = 0.275,

while the math for the upper bound is

.940 × .90 × .95 × .92 = 0.739.

It's also interesting to quantify things in terms of money. If we use the new (October 2022) UK price caps, it costs something like £0.28 to heat the water for a bath or shower. So, scavenging the heat would save around £0.13 each time. That's assuming you heat your water with gas. If you heat your water with pricey electricity, you should triple those numbers.

A reasonable estimate is that taking a full (80 liter) bath uses around 2.7 kWh of energy, while a shower might use around 0.33 kWh per minute. If you take an (average) 8-minute shower and use a (typical) 10 liters per minute, that would be a similar amount of water and a similar amount of energy.

As of October, the price cap in the UK is £0.104 per kWh for natural gas. So if you have a gas water heater (as most people in the UK do), a full bath or shower costs around £0.104 × 2.7= £0.28. Scavenging the heat could save 48% of that, or £0.13. If you’re on electricity, the cap is £0.34/kWh, meaning that a full bath or shower costs around £0.34×2.7=£0.92. Again, scavenging the heat could save 48% of that, or £0.44.

Should you do this?

I render no judgment!

But here’s a thought: It’s OK to use energy for convenience. This is true even in a time of crisis. After all, only a small fraction of the energy we use is necessary to stay alive. We could live dirty and shivering in dark rooms, eating oats and only moving around on foot. But no one does. So the question is how much energy you want to use for how much convenience.

But if you have an appetite for sacrifice—either for yourself or out of public spiritedness—you should sacrifice efficiently. If you’re already trying to shorten your showers, and you hate short showers, but you wouldn’t mind letting shower water sit around for a while, then here’s some free utility.

Thoughts

Many animals—reindeer, penguins, wolves, otters, arctic foxes—use a strategy called countercurrent exchange when circulating their blood. The idea is that hot blood goes out to the extremities and then gets cooled by the air/ice/ground/water. To reduce the wasted energy, veins with cool incoming blood are alongside arteries with hot outgoing blood. This means that some of the heat in the outgoing blood is transferred to the incoming blood and so less energy is sent out into the environment.

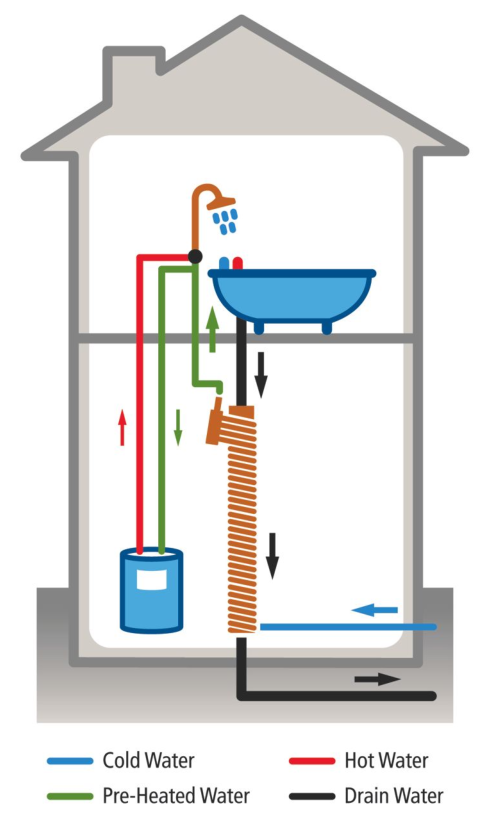

You can install a device in your home to do something similar—have your warm wastewater heat up the cold incoming tapwater. This is called a drain-water heat recovery system. Here’s an image from Wikipedia:

The idea of these is brutally simple: Route the outgoing warm water so that it heats the incoming tap water, reducing the amount of work for the water heater to do. These devices have no moving parts, require zero effort to use, need little maintenance, and are fairly cheap (on the order of a few hundred dollars). Typical estimates are that they would pay for themselves in just a few years. However, they don’t yet seem to be in widespread use for whatever reason.

In any case, there are a few downsides to the idea of collecting heat by letting water sit around:

-

It would be tricky to collect water with some showers:

It would be even harder with the totally-flat doorless monstrosities the world seems to be lurching towards.

-

Does it sound unpleasant to stick your hand into cold dirty water to remove a drain plug? In my experience, it’s even worse than it sounds. Use a stick or a chain.

-

It’s mildly unpleasant to stand in collecting water while showering. You could add a platform but please do not do that—it’s frighteningly common for people to get hurt by slipping in the shower and anything you add might increase the risk. (Better idea: Make sure you have a high-friction surface in your shower, especially if you have anyone young or old in the household.)

-

Extra moisture in the air might cause problems with things like mold. Use your judgment. It’s probably fine as long as things don’t stay damp for long periods. For many, extra humidity in the air would be welcome. (Maybe you can stop using that ultrasonic humidifier.)

-

You’ll probably have to clean more often. Or—you know—have less limiting standards of cleanliness.

-

Update: gumboid points out that evaporating water subtracts heat. If I have the math right, a single liter of evaporating water pulls around 0.63 kWh of heat from the air. This seems important! But I’m not sure how to think about it. If it displaces energy that you would have otherwise spent on a humidifier, then it’s neutral or even maybe extra savings. And showers probably already spike humidity to near saturation, so maybe you can get much of the heat with little extra evaporation. At a minimum, if you like dry air, then it’s likely a bad idea to leave cold water sitting around overnight.

The rest of this post will detail how I came up with all the numbers I used above. As always, I know the internet hivemind is smarter than me and I welcome any corrections.

Domestic energy

First of all what fraction of the UK’s energy is used in homes rather than say in businesses or in transportation? The ECUK 2022 report (consumption data table C1) tells us that in 2021 the domestic sector in the UK used 41,115 kilo tonnes of oil equivalent (ktoe) out of a total usage of 134,099 ktoe in all sectors. So the domestic sector consumes 30.7% of energy.

This figure was a bit lower pre-COVID: It had gradually declined from 32.8% in 2010 to 26.1% in 2019. It’s hard to say what exactly 2023 will look like—the situation is novel—but I think the best guess is to revert the 2021 number a bit toward the pre-COVID environment. So I’ll use 29%. I think it’s very likely to be in the range between 26% and 32%.

Domestic water

Next, what fraction of domestic energy is used for heating water? We can again consult the ECUK 2022 report (end use table U2) to get that in 2021 domestic water used 7,359 ktoe out of a total domestic usage of 41,019 ktoe. (This total is 96 ktoe different from table C1 for reasons I don’t understand but I decided it wasn’t worth agonizing about a difference of 0.23%.) This means domestic water is 17.9% of domestic energy usage. In 2019 the same calculation gives 17.6%. The data doesn’t go back further than 2017 when it was 17.3%.

This seems in line with research in the US that suggests 17%. So I think 17.5% is a pretty good estimate. Since the number barely changed under COVID I suspect it won’t change much in the future, so I’ll use an uncertainty range of 16.5% to 18.5%.

Putting this together with the number in the previous section we get that 29% × 17.5% = 5.1% of all UK energy usage is for hot water. You might hope that this means 5.1% of all UK energy could be saved by scavenging the heat in bathwater. But that’s wrong for many different reasons. I’ll cover them in the order they physically occur.

Water heater efficiency

Not all the energy that goes into hot water heaters actually goes into the water. In 2003, the most common water heater in the UK was a standard gas boiler, which wastes a lot of hot gas. These have an efficiency ranging from around 60% in older models to 80% in newer ones. But since 2005, any boiler that’s installed or replaced in England and Wales must by law be a condensing boiler that tries to “condense” the gasses back into a liquid form so the heat can be re-used. These typically have an efficiency of over 90%, with some manufacturers claiming numbers as high as 98%.

In 2019, 73.8% of homes had a condensing boiler, 16.6% had some other kind of boiler, and 9.7% had no boiler. But condensing boilers are surely more common now: In 2016 they were only 62.7% with 26.9% having another type of boiler. Extrapolating, we would expect that in 2022, 84.9% of homes would have a condensing boiler and 6.2% some other kind of boiler. That feels slightly aggressive, so I’ll only go half as far and call it 79% of homes with a condensing boiler and 11% with another boiler.

I'll assume an average efficiency of 90% for condensing boilers and 75% for other boilers, and ignore the no-boiler homes. As a lower-bound, I'll assume no change from 2019, that condensing boilers are 90% efficient and other boilers are only 60% efficient. As an upper-bound, I'll use the full extrapolation over time, put condensing boilers at 95% and other boilers at 80%. Using all these gives a point estimate of 88.2%, with an uncertainty band of 84.5% to 94.0%.

- Point estimate: (79 × 90 + 11 × 75) / (79 + 11) = 88.2%

- Lower-bound: (73.8 × 90 + 16.6 × 60) / (73.8 + 16.6) = 84.5%

- Upper-bound: (84.9 × 95 + 6.2 × 80) / (84.9 + 6.2) = 94.0%

Incidentally, there are heat exchanger water heaters that are more than 100% efficient. A company called Roper claims efficiency of around 129% but real-world tests suggest something more like 106%. Fortunately—for my calculation if not the world—these still seem to be pretty rare.

Water usage

Not all hot water is used for bathing—it’s also used in sinks, laundry, and dishwashers. Sadly, I wasn’t able to find any reliable society-wide surveys on this. In the UK, the best I could find was the 2011 report “Measurement of domestic hot water consumption in dwellings”, which provides a full accounting of usage only in a single dwelling, where baths plus showers made up a bit over 75% of energy usage. Parker et al. (2015) cite Lowenstein and Hiller (1998) as finding showers and baths consume 51% and Henze et al. (2002) as finding they used 59%.

One concern here is dishwasher usage. Dishwashing machines use less energy than washing by hand. (Everyone who has a dishwasher but doesn’t use it—are you OK?) Something like half of households in the United Kingdom (UK) own a dishwasher. This is just slightly less than in the US, but maybe usage rates vary much more. Also, the above data was collected more than 20 years ago.

So I’ll estimate that 50% of hot water is used for showers and baths. But I have high uncertainty, so I’ll use a range of 35% to 80%.

Delivered heat

Not all of the heat that is in water when it comes out of the water heater is still there when it emerges in the shower or bath or sink.

There are two things to think about here. Firstly, how much water comes out of the tap before the water gets hot? Well, that water used to be hot: You filled the pipe with hot water the last time you showered, and all the heat was lost while the water was sitting there. Second, even when water is flowing, heat is lost in transit.

Parker et al. (2015) estimate that around 20% of the heat in water ends up wasted in this way. This seems a bit high to me for several reasons: The fraction of wasted water is smaller with showers than with washing hands since you’re using a larger volume. And the boilers now common in UK households tend to be closer to the destination to minimize these losses. I’ll use 80% as the percentage of delivered heat, with uncertainty from 70% to 90%.

Currently recovered energy

Some of the heat in your water already ends up as heat in the air in your home. (Notice how the bathroom gets hot when you shower?) That’s a positive thing, but energy that’s already saved can’t be saved again, so we need to account for this.

Hinchcliffe (2012) estimates that around 90% of the heat that comes out of the shower ultimately goes down the drain. Common sense suggests the number would be lower with baths since the water spends so much longer between the pipes. I couldn’t find any clear estimates, but in any case, people in the UK take showers much more often than baths. So I’ll use 85% with a range of 75% to 95%.

Recoverable energy

You might think that we’re done. But no!

You can’t recover all the heat in your water. The water that flows into your water heater is (presumably) colder than your home. But your shower water stops giving you heat back once it has cooled to air temperature, not tap water temperature. So the fraction of recoverable heat is

(Shower temperature - room temperature) / (Shower temperature - tap temperature).

The 2011 report “Measurement of domestic hot water consumption in dwellings”, suggests that tap water in the UK is typically around 12 °C. in winter. This 2013 report found the mean indoor temperature was around 18.5 °C in UK households in winter. People like to bathe in water that’s slightly above body temperature, so I’ll conservatively estimate 38 °C. (It’s better for your skin if it’s just lukewarm.) For a lower-bound, I’ll use 36 °C showers, 20 °C room temp, and 10 °C incoming water, while for an upper-bound, I’ll use 40 °C showers, 16 °C room temp, and 14 °C incoming water.

All this leads to a point estimate of 75% of heat being recoverable, with a range of 62% to 92%.

For a point estimate, the fraction of recoverable heat is

(38 - 18.5) / (38 - 12) = 75%.

If we use pessimistic numbers (36 °C showers, 20 °C room temp, 10 °C incoming water) the calculation is

(36 - 20) / (36 - 10) = 62%.

If we use optimistic numbers (40 °C showers, 16 °C room temp, 14 °C incoming water) the calculation is

(40 - 16) / (40 - 14) = 92%.

You might be thinking: Doesn’t much of the heat that’s lost from water to pipes end up in the home? That’s surely true, but it doesn’t matter for our calculation. Regardless of if that energy is getting wasted or saved now, getting more heat out of bathwater won’t change anything.

This difference between air temperature and tapwater temperature is one subtle way that toilets use energy—cold water steals heat from the environment. But this isn't a huge amount: Assuming a 6.5-degree temperature difference and 5 liters of water used to flush it ends up at 0.038 kWh. That's not a lot—even at the current (very high) energy price caps in the UK, it would cost at most something like 1 penny per flush. (In principle this might save you money on air conditioning in summer, but few homes in the UK have air conditioning.)

The calculation is that

6.5 × 5 l × 0.001162778 kWh/ (kg × degree) = 0.038 kWh.

Assuming you pay 34p / kWh (electric heat and current electric price cap) that’s £0.013. Assuming you pay 10.4p / kWh (gas heat and current gas price cap) that’s just £0.004.

Personal consumption

Let’s say you take a full bath using 80 l of water. Or, you take an (average) 8-minute shower using (an average ) 8-liters per minute. How much energy does that use?

We just need a few facts. The specific heat of water is 0.001163 kWh / (kg × degree). Let's assume that your tap water is 12 °C, you bathe with 38 °C water, and your water heater is 90% efficient. It happens that 1 l of water weighs 1 kg (thank you metric system). Then some simple arithmetic gives us that the shower/bath uses around 2.7 kWh.

(38 degrees - 12 degrees) × 80 l × 0.001163 kWh/ (kg × degree) × (1 kg / l) / .90 = 2.687 kWh.