In June of 1812 Napoleon assembled the largest European army in history and invaded Russia. After months of bloody fighting, the French finally arrived in Moscow in September, surprised to find the city mostly abandoned. That night, remaining Russians set fires across the city, eventually burning most of it to the ground. After camping in the ruins for a month, Napoleon realized that the Russians had no intention to sue for peace, supplies were dwindling, and their prospects over the winter were bleak without a living city to sustain them. In October, the French retreated, eventually leaving Russia in defeat in December.

It turns out that the body fights viruses using a similar tactic.

You’ve probably heard that T-cells are important for immunity to COVID-19. But what exactly do T-cells do? How do you get immunity? What’s the difference in what happens after exposure to the virus when someone is immune?

It’s debated if the Russians intended to completely destroy Moscow, but never mind. Imagine you wanted to implement “destroy your cities ahead of the French” as a deliberate strategy. If so, you’d want to be very careful that the French were actually coming before burning one down. Scouts can be unreliable, and who knows what the French army really looks like? (It’s 1812, photography hasn’t really been invented yet.) You’d probably require the city authorities vote unanimously before going ahead. It’s better to risk the French capturing a city than to risk burning one down unnecessarily.

But suppose you have a unit that fought the French for a month and captured some uniforms and equipment. You could distribute these soldiers and detritus to different cities, with orders that cities be immediately burned when they say so. Since they are familiar with the French, false alarms are much less likely.

That’s kind of how the immune system works. All our cells are built with a self-destruct mechanism called apoptosis built in. When there is a viral infection, our T-cells activate this mechanism on all the nearby cells to deny the virus any place to replicate. But the body doesn’t want this to happen by mistake—that’s how you get autoimmune disease. Thus, T-cells require a lot of signal that there’s an invasion before they activate, meaning a long ramp-up period. However, once activated, some T-cells will store specific patterns from the virus, and become “memory” T-cells. These move around the body and are programmed to activate very quickly, but only when they see the specific pattern they have stored.

I came to this strange analogy after pestering my biologist friends to explain COVID-19 to me. My feeling was that journal articles for experts assume a Biologist Mental Toolkit that I lack. Still, I felt it should be possible to give more detail to someone like me with a Generic Science Background. With their enormous forbearance, I was able to extract an explanation that could fit into my tiny non-biologist brain. This post gives that explanation in the form of a fictional interview.

Here are some of the most surprising things I learned:

-

Signaling. The immune system is mostly a madhouse of everything signaling everything else, and rarely “doing” anything. Maybe this is a deep strategy to counter autoimmune disorders or parasites or cancer.

-

A machine that makes a machine make a machine that makes a machine. Everyone knows that viruses use cells to make proteins. But the COVID-19 virus is a bunch of proteins, plus RNA that says how to make all the proteins. How does the virus make copies of the RNA itself? The virus builds an enzyme inside the cell that makes copies of the RNA!

-

Immunity and memory cells. Immunity isn’t really about antibodies. It’s about memory B-cells which make antibodies (and do other stuff) and memory T-cells which trigger other cells’ suicide program (and do other stuff).

-

Why we need memory cells. Memory B-cells remember how to make virus-specific antibodies. But T-cells just sort of tell everything nearby to kill itself (apoptosis). Regular T-cells can already sense foreign proteins and can already trigger apoptosis, so why do we need memory T-cells at all? It seems to be an issue of tuning. Regular T-cells need a lot of signal to activate. (It’s a good idea to be sure before handing out suicide orders.) Memory T-cells activate faster, but only for specific patterns they remember. Memory cells are how the body knows this virus is something to take seriously.

-

Immunity and cell death. It’s well-known that RNA vaccines use your cells to make proteins that are part of the virus. When those proteins float around in the body, they will cause an immune response. But the proteins are made inside cells. How do they get out? You basically just wait until the cells die and break apart.

Two notes about the content below:

-

I focus on the rare cases where something actually does any “work”. My biologist friends agree that the explanation below is correct, but are pained by the details not included. (“Interferon types (I/II/III) are the foundation of the entire immune system!”)

-

There are a few things the biologists seemed to believe, but were unwilling to endorse. I give these as clearly marked asides.

How viruses work

How does COVID-19 work?

COVID-19 is a single-stranded RNA virus. This means it enters a cell and then releases the RNA inside the virus into the cytoplasm of the cell 1 2.

How does it get into the cell?

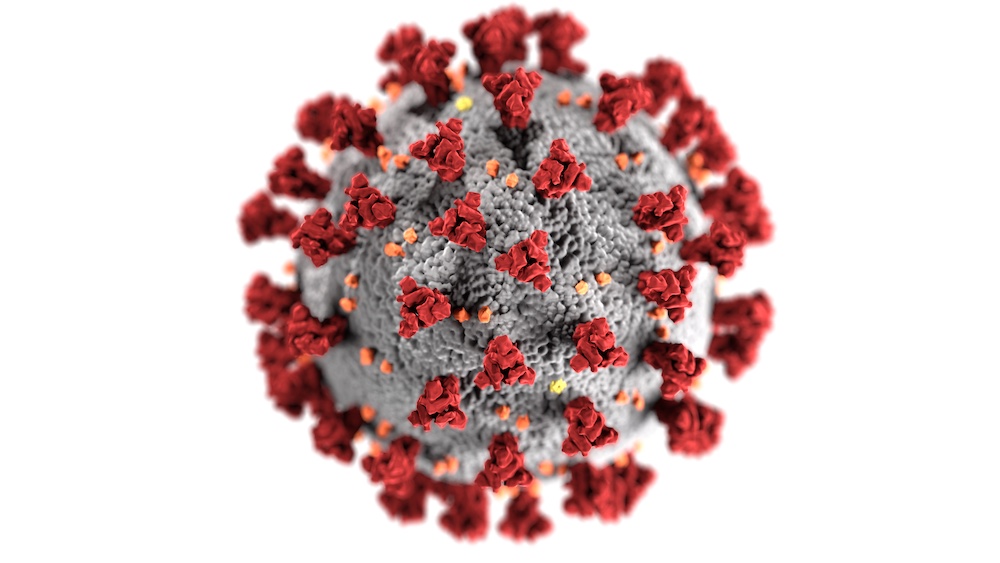

Cells have many receptors that bind to specific molecules and transport them inside the cell. COVID-19 has a “spike” protein on its surface that binds predominantly to the ACE2 receptor. Cells that have higher density of ACE2 receptors seem to be more susceptible to the virus. There may be other receptors or mechanism that may be involved, but ACE2 seems to be the biggest factor 1 2.

Why is this called a “spike” protein?

It protrudes from the surface of the virus and looks like a spike.

OK, the viral RNA is now in the cytoplasm of the cell. What happens next?

The infected cell’s machinery will generate viral proteins. Amino acids are floating around in the cytoplasm. The cell’s ribosome first attaches to one end of the viral RNA. The first amino acid coded by the RNA arrives and is attached. The ribosome moves on to the next RNA code and again attaches the corresponding amino acid. This continues until the ribosome reaches the termination code, at which point it’s done making one protein 1 2.

How many different proteins does COVID-19 make?

A bunch. The virus injects multiple strands of RNA and gets multiple proteins at the end. There are four key proteins: Those that make the spike, the envelope, the membrane and RNA-polymerase.

So the virus is trying to make new copies of itself. Doesn’t it need to also make new RNA to go inside the viruses, so the whole process can be repeated at other cells?

Oh, yes. The RNA polymerase is an enzyme that makes copies of the viral RNA inside the cell.

After the proteins and new RNA are made, what happens next?

They assemble together into new viruses. The proteins and RNA are formed so that this assembly happens naturally. Eventually, they will get out of the cell. For some viruses this can happen by breaking the cell apart, or exhausting the resources of the cell and waiting for it to die. COVID-19 seems to be an envelope virus that is able to get through the cell membrane without killing the cell. This exit can happen in numerous ways. Eventually the cell does die because the resources are exhausted but the virus can escape and replicate before that 3.

How many viruses result from a single cell being infected?

I don’t know. For other viruses this can be as low as around 40 or as high as 50,000. For viruses related to COVID-19, this is typically on the order of a few hundred.

Why does COVID-19 make people sick?

Most of the symptoms (cough, fever, etc.) are caused by the activated immune system, not directly by the virus. We still don’t fully understand why COVID-19 makes some people so sick. There are several factors that contribute to severity, such as the person’s age, how many virus particles they inhaled, and if they have pre-existing chronic conditions. A recent paper suggested that variations in genes affect how the immune system behaves also impact severity. As COVID-19 enters through our respiratory pathways, some people suffer from complications due to a hyper-inflammatory response that severely affects the cells in our lungs, impairing breathing and so on 4 5.

The three fundamental mechanisms

How does the immune system kill viruses?

There are three fundamental strategies. The first is to make it harder for viruses to enter cells. The second is to cause infected cells to die. The third is to make it harder for viruses to replicate inside of cells. The third of these is less understood. Currently, immunity seems to be more about the first two mechanisms.

The biologists refused to say which of these is most important, I think because it’s heretical in the biology belief system to ever say that anything is more “important” than anything else. I also get hints that the third mechanism is a little neglected because it isn’t a sexy research topic.

How does the body make it harder for viruses to enter cells?

The body has immune cells called B-cells. Some of these make and secrete proteins called antibodies that bind to viruses freely-floating between cells. These will nearly “cover” the virus. In the case of COVID-19, this hides the spike protein, meaning it can’t get inside of cells. Eventually macrophages will come and eat the antibody-covered viruses. (The macrophages don’t usually eat the antibodies themselves.)

How does the body cause infected cells to die?

There are basically two ways. First, there are specialized immune cells called natural killer cells that will kill virally infected cells. Second, our cells are built to essentially “commit suicide” when signaled to do so. This is called “apoptosis”.

This is how we fight viruses? By killing parts of ourselves before the virus can? The biologists stubbornly refused to make any comparison of the importance of apoptosis relative to other parts of the immune system or even to endorse that it was a “fundamental” part of the immune system. Again, I’m convinced this due to indoctrination and that they secretly believe that apoptosis is “very important”. Anyway, you should probably ignore me.

Immunity

What is the physical difference between a person who is immune to COVID-19 and a person who is not immune?

Someone is immune to COVID-19 because they have memory T-cells and memory B-cells that “remember” protein fragments from the virus.

Suppose someone who is immune is exposed to the virus. What is the difference between what happens in their body and what happens in someone who is not immune?

As I mentioned before, the immune system has many mechanisms and many types of specialized immune cells. However, B-cells and T-cells are particularly important to immunity. I mentioned B-cells before: They make antibodies that bind to viruses to prevent entry into cells and make the viruses easier to kill. B-cells also signal to other immune cells, mostly T-cells.

What do T-cells do?

T-cells store special proteins called cytokines and spit them out at appropriate times. These have various effects. Some “signaling” cytokines signal other immune cells (of all types) to come to this location. Other “cytotoxic” cytokines enter cells (it’s not known how) and then give a message to commit suicide.

How do T-cells know when they should do this?

All cells have the ability to chop up foreign protein fragments that have invaded them. They then “present” the chopped up fragments on their surface so that immune cells can see them. T-cells have an inherent ability to not react to your body’s own protein fragments (unless you have an autoimmune disease). How they do this isn’t fully understood yet. But if they see a foreign protein, they initiate an immune response 6. This response takes a long time to ramp up in a non-immune person. Memory T-cells and B-cells have “remembered” a protein fragment from the virus. If they see it again, the immune response will ramp up much faster and in a more focused way.

This was a huge point of confusion for me. It’s clearly true that memory B-cells and T-cells make the immune system ramp up faster on subsequent exposure. But how do they do this? Memory B-cells are ready and waiting to make virus-specific antibodies. But what capabilities do memory T-cells have that regular T-cells don’t? The answer seems to be that it’s not about their capabilies but their “programming”. For a regular T-cell there needs to be a lot of signal applied to make it activate. This is probably because spurious immune reactions are very harmful. But if a memory T-cell sees the protein fragment it’s stored, it knows immediately that this is serious and activates.

How do you get memory B-cells and T-cells?

There are two things to understand here. First, when viruses are floating between cells, they can be “grabbed” by a specialized immune cell called an antigen-presenting cell (APC). APCs chop up the viral proteins and present them on their surface. Second, your body starts with “naive” B-cells and T-cells. If a foreign protein fragment is presented to them by an APC, some of these naive cells will “remember” the fragment and specialize to become memory cells. These memory cells will then move around to different parts of the body, e.g. to the lymph nodes

Wait, so why are we testing for COVID immunity by testing for antibodies? Shouldn’t we be testing for memory B-cells or T-cells?

After fighting off the virus, antibodies will circulate in the body for a while. It depends on the disease. We don’t know for sure how long this is for COVID-19, but some recent reports suggest up to 5 months 7. However, this study isn’t conclusive. A negative antibody test doesn’t that you haven’t had COVID-19 or that you aren’t immune from it. We will learn a lot more about antibody stability as we collect more data from infected patients.

We don’t test for memory T-cells or B-cells because we don’t know how to do it. Antibodies are simple proteins floating around in the body. Memory cells are in specific locations, and it’s very difficult to tell if they are specialized for COVID-19 or for chicken pox or whatever.

Vaccines

How do COVID vaccines work?

There’s different varieties, but the basic idea is very simple: We want to present a protein fragment to the body to trigger an immune response that is small, but enough to create the memory B-cells and T-cells so that if the actual virus ever shows up it will immediately be killed.

I’ve heard that the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines are “RNA” vaccines. How do those work?

We create specific “messenger RNA” sequences and encapsulate them in a lipid nanoparticle. This is injected into the body. Because of physics, that nanoparticle will naturally cross the cell membrane and then dissolve, leaving the RNA inside of cells. The body’s protein machinery (ribosomes etc) then makes this into a specific protein. We have chosen the RNA sequence to make the spike protein of the COVID-19 virus.

Why “messenger” RNA? No one could identify a physical difference between messenger RNA and regular RNA. I think it’s an issue of intent, e.g. if the RNA is carrying a “message” from the DNA in the nucleus. I wanted to delete the word “messenger” from the previous answer, but this would have caused a mutiny.

Why code for that specific protein?

This protein is on the surface of the virus, so it is always visible. We also guess that this part of the virus is likely not to change if the virus mutates.

How does that spike protein get out of the cells?

The cells will naturally present fragments of the protein on their surface. This will start an immune response, but probably not create memory cells. However, when the vaccinated cell dies, the protein gets released into the body. These will get picked up by the APCs and lead to memory cells. This seems “slow” since you have to wait for cells to die. However, it seems that some of the vaccine will by chance enter directly into APCs. If this happens, the APCs will manufacture the protein, and then immediately present to form memory cells without the APC needing to die first.

If I take the Moderna or Pfizer vaccine, what’s the risk that something goes wrong and I end up getting a serious COVID-19 infection?

The risk of getting COVID-19 from the vaccine is zero. You are only putting the sequence for the spike protein into your body. The rest of the virus isn’t present in any form. There is no “inactivated” virus like in a traditional vaccine, and there’s nothing to code for the rest of the virus. It’s impossible. These are probably the safest types of vaccines ever created. Even our flu vaccines are basically inactivated flu virus cocktails, and we don’t worry about those.

Update (Sep. 2021): I was chatting recently with the biologist who made this “safest vaccine ever created” remark. They wouldn’t make that claim at this point, and in fact don’t remember saying it. (Though they did!) They still believe the risk from these vaccines is miniscule compared to the risk posed by getting COVID. They got vaccinated as soon as they possibly could, and still recommend the same for everyone else.

For any immunologists reading this

Obviously, I’d be grateful for any corrections. Also, here’s two questions we couldn’t resolve. If you know the answer (particularly if you can explain it in Human) please get in touch!

- In order for RNA vaccines to work, is it really necessary for the host cell to die? If so, why does the cell die? Is it just by chance, or does it die because of the vaccine?

- There’s a story about how you might get immunity faster, without needing to wait for a cell to die: Some vaccine particles might happen to direclty enter into antigen presenting cells (APCs). If that happens, the APCs would make the spike protein, just like any other cell, but then immediately present it on their surface without needing to die, allowing memory cells to form quickly. Does this really happen? And does it happen enough to actually speed immunity? Wouldn’t only a tiny percentage of the vaccine particles happen to hit APCs?

References

-

Shah et al., Overview of Immune Response During SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Lessons From the Past, Frontiers in Immunology, 2020 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Li et al. SARS‐CoV‐2: Mechanism of infection and emerging technologies for future prospects, Reviews in Medical Virology, 2020 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Bruce Goldman, The invader, Stanford Medicine, 2020 ↩

-

Pairo-Castineira et al., Genetic mechanisms of critical illness in Covid-19, Nature, 2020 ↩

-

Claudia Wallis, Why Some People Get Terribly Sick from COVID-19 Scientific American, 2020 ↩

-

Andrew K. Sewell, Why must T cells be cross-reactive?, Nature Reviews in Immunology, 2012 ↩

-

Wajnberg et al., Robust neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 infection persist for months, Science, 2020 ↩