1.

You’re in the mood for destruction. One day, you hear about this phenomenon of “radiation” where matter gives off energy. You think—perhaps you can harness this property of nature to make a big boom.

Apparently matter is made of discrete objects called atoms, which have nuclei made up of protons and neutrons. To say that an atom is “radioactive” is to say that it sometimes randomly does things like:

- Eject a neutron. (“neutron emission”)

- Eject a group of 2 neutrons and 2 protons. (“α decay”)

- Transform a proton into a neutron or vice-versa, in the process either ejecting a positron plus a neutrino or an electron plus an anti-neutrino. (“β decay”)

- Split into two smaller atoms plus some number of neutrons. (“nuclear fission”)

How often these things happen depends on how many protons and neutrons are in the nucleus. Of the above, fission releases the most energy by far so you decide to use fission to make your boom.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to find atoms that do much spontaneous fission. A plutonium-240 atom decays on average after 6569 years, and when that happens, there’s only a 0.0005% probability of fission, rather than α decay or whatever.

And even if you somehow assembled a big pile of atoms that wanted to undergo spontaneous fission, they would…undergo spontaneous fission, and start being different atoms. You need to build something you can trigger.

In search of a trigger, you eventually try shooting neutrons and protons at atoms. The protons get repelled by electrical charges, but neutrons sometimes get absorbed into the nucleus.

Often, the effects of neutron absorption are mundane. Hitting cobalt-59 with a neutron produces cobalt-60, but all cobalt-60 does is slowly decay (via β-decay, with a half-life of 5.27 years) into nickel-60.

But if you hit a nucleus with a fast-moving neutron, that can induce fission. With enough kinetic energy, you can make basically any heavy atom undergo fission in this way, generating energy in the process.

To make a weapon, you need to suddenly, on demand, fire astronomical neutrons at all your atoms. How are you going to do that?

2.

What you need is some kind of chain reaction—that the neutrons that are emitted by the fission of one atom can also cause fission in other atoms. Usually, this doesn’t happen. A high-energy neutron can cause fission in uranium-238, but the neutrons it puts out don’t have enough energy to break up other uranium-238 atoms in the same way.

So you look for atoms where a fission reaction could self-sustain. You find a bunch:

- Uranium-233, 235

- Neptunium-236, 237

- Plutonium-238, 239, 240, 241, 242

- Americium-241,242m,243

- Curium-243, 244, 245, 246, 247

- Califonium-249, 251, 252

- Berkelium-247, 249

- Einsteinium-254

But there’s a problem. These are all very heavy atoms, basically because those are easy to break apart. But for the same reason, they are all radioactive, meaning they also tend to spontaneously decay, and thus stop existing.

For example, Curium-247 has one of the longest half-lives in the above list, 15.6 million years. Trouble is, the Earth is 4.6 billion years old, meaning 249.9 half-lives have passed since the planet was formed. Of whatever primordial Curium-247 once existed, only 0.0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000017% is still around.

You need an atom that both (a) can sustain a chain reaction of fissions, but (b) has a long-enough half-life that you have some hope of actually finding it somewhere on Earth.

Checking carefully, you realize you have exactly one option: Uranium-235, with a half-life of 703.8 million years.

3.

Say there’s a block of U-235 sitting somewhere. A few atoms will constantly undergo spontaneous fission and spit out neutrons. If the block is small, the neutrons will probably just escape, since the nuclei of other atoms are tiny and hard to hit. As the block gets bigger, there are more chances for each neutron to get captured by another U-235 atom. Once the block is big enough, the probabilities should work out that each fission will trigger—on average—more than one fission, leading to a chain reaction.

How big a block do you need? You do some experiments shooting neutrons and measuring secondary fissions in small blocks. The math says that the critical mass of U-235, when shaped into a sphere, is 52 kg. Any more than this, and you’ll get exponential growth in fission reactions.

How hard will it be to get your hands on 52 kg of U-235?

First, the good news: Uranium is fairly common. The Earth’s crust is 0.00027% uranium, 36 times more than silver and 675 times more than gold. It’s basically everywhere—in oceans, lakes, dirt, rocks, everything you eat, everything you drink, etc. And thanks to the long half-life, it’s not particularly radioactive. As long as you don’t ingest too much, it won’t really hurt you.

Now, the bad news: The uranium on earth is only 0.7% U-235 with the rest being useless U-238. So you need to start with at least 52 kg / .007 ≈ 7,429 kg of natural uranium.

And: You can’t find any convenient piles of uranium lying around. You consider using seawater, but that’s only 0.00000033% uranium. To get 7429 kg of uranium out, you’d need to process a cubic block of water that’s 1.3 km on all sides, or more than would fill 600,000 Olympic swimming pools.

So you spend a few decades scouring the earth and eventually find a high-grade deposit that’s around 16% uranium, conveniently located 450m underground beneath a lake in northern Saskatchewan. You put on a hazmat suit to make sure you don’t breathe any of the dust and go dig up 7,429 kg/0.16 = 46,429 kg of this rock, a bit more than can be carried by two semi-trailers.

Now, you need to separate the uranium from the rest of the rock. After a quick chemistry PhD, you crush the ore, grind it into fine sand, and roast it to burn off any carbon. Then you mix it with sulphuric acid and an oxidant, which absorbs the uranium into the acid solution. After filtering and discarding the solids, you force the uranium to precipitate out of the solution using solvent extraction or ion exchange, and you’ve got yourself a big pile of triuranium octoxide (U3O8) or “yellowcake”.

4.

At this point, things start to get difficult.

The atoms in your yellowcake are still only 0.7% U-235, which you need to isolate from the 99.3% of U-238. The problem is, since these have the same number of protons, they look the same to electrons, making them chemically identical—they have the same melting point, the same boiling point, and react to every other chemical in the same way, etc.

You realize in despair that the only thing you have to go on is that U-238 is slightly heavier than U-235, on account of having three extra neutrons. So you decide to create “fake gravity” using a centrifuge. For this to work you need to first transform the uranium into a gas, with several requirements:

- It should be a solid at ordinary Earth pressure/temperature, but sublime into a gas with mild changes to these without going through an intermediate liquid phase that would confuse things.

- Whatever molecule is formed should have only a single uranium atom in it. You don’t want to deal with molecules that have, say, one U-235 atom, and two U-238 atoms.

- Whatever other atoms you combine the uranium with must themselves have only a single stable isotope. If they also had varying numbers of neutrons that would mask the differences in the uranium.

Luckily, there’s a gas that meets all these requirements, namely uranium hexafluoride (UF6). You put some of this in a cylinder and spin it around. Here’s what you notice:

- You need to spin really fast to create enough centrifugal force to get any separation between the different types of uranium. The outside wall needs to move at something like 500 meters/second, which causes your cylinder to tear itself apart. To stop this from happening, you build a very strong and well-balanced cylinder.

- When you spin the gas at this high speed, the pressure condenses some of the UF6 back into a solid, halting all separation. To stop this, you create a vacuum inside the cylinder and only feed in small amounts of UF6 at once.

- The 1% difference in weight means the U-238 atoms tend to get pulled to the outermost part of the cylinder. However, this is fighting against random molecular diffusion, meaning your spinning cylinder only produces a very slight difference in the concentration of U-235.

So you kidnap some scientists, who advise you to make the bottom of the cylinder hotter than the top, creating a gentle vertical rotation in which the inner—more U-235 rich—gas slowly rises while the outer—more U-238 rich—gas falls. For deranged continuum fluid mechanics reasons, this amplifies the small radial difference in U-235 concentration into a larger vertical difference. You sip U-235 enriched gas from the top of the tube and depleted gas from the bottom.

And still, after all this work, your centrifuge just isn’t very good. Starting with natural 0.70% U-235 gas, the best you can do is generate 0.79% enriched gas and 0.64% depleted gas.

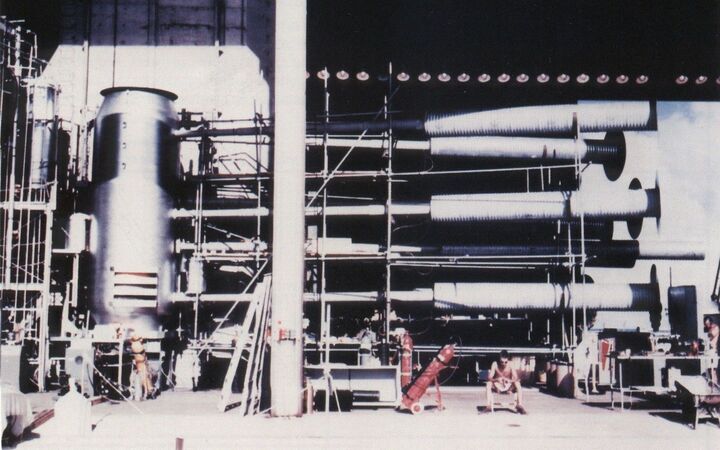

So: Brute force. You set up a series of dozens of centrifuges, each of which produces slightly more enriched gas, with a final output that is nearly pure U-235.

Of course, if you threw away the depleted gas from each stage, you’d have almost nothing left at the end. So instead, you feed the depleted gas from higher stages back into lower stages for recycling. You also build a few levels below the original stage to recycle the depleted gas. Once the U-235 content gets to a low enough level (say 0.2%) you carefully dispose of it in a safe location or make it into artillery shells for tanks or whatever.

You end up with a pyramid design with many centrifuges operating in parallel on the original 0.7% uranium, and fewer centrifuges as concentrations get lower or higher.

And still. Still, this giant machine you’ve built can only process UF6 very slowly. Even with a thousand centrifuges you can only extract around 2.5 kg of U-235 per month. So you rebuild all the machines for incredible reliability, hire engineers to be on hand 24-7 to fix anything that breaks, wait a few years, and finally get your 52 kg of U-235.

5.

Now hopefully when you made all this U-235, you didn’t keep it all together. Because—I should have mentioned this—spontaneous fissions in the uranium would start the chain reaction and your material would detonate and you’d die.

The good news is that you’re close to having a weapon. All you need to do is form the U-235 into two pieces, put them in the vicinity of whatever you want to destroy, and then very quickly fit the pieces together.

How to do this? If you shoot two bricks at each other, they’ll likely just bounce. You need to shape the pieces so that they will mesh together. You decide to form one hollow cylinder and one plug that fits perfectly inside the cylinder. You put both of these inside a tube, with an explosive behind the cylinder. When that explosive goes off, the cylinder shoots down the tube and engulfs the plug, establishing a critical mass for fissile reactions to grow exponentially and—boom.

6.

We are very lucky this is so hard.

Further reading

See also:

- Wikipedia: Nuclear binding energy, list of uranium projects

- Roots of progress: I walk the (beta-stability) line

- RationalWiki: FAQ on radioactivity and nuclear technology

Notes:

- The Zippe-type centrifuge was invented by Austrian and German scientists captured by the USSR after WWII.

- In reality, you’d never obtain pure 100% U-235. People use something like 90% U-235, which has a larger critical mass. But you’d also probably put a metal like beryllium around the mass to reflect the neutrons back in, which dramatically decreases the critical mass.

- Apparently in the US you can own as much uranium ore as you want, but you aren’t allowed to possess more than 1.5 kg of yellowcake.

- The technique I described of mining and then refining uranium ore is becoming obsolete. Instead, in-situ leach mining is used where chemicals are added directly to the ground to dissolve the uranium and then only that liquid is pumped out without the rest of the rock.

- U-235 and U-238 may not be 100% chemically identical—a project in France is working on a chemical separation method that would exploit “a very slight difference in the two isotopes’ propensity to change valency in oxidation/reduction”.

- Centrifuges won’t actually recover all of the 0.7% of U-235 in yellowcake. But apparently it is possible to recover the majority of it.

- My estimates for the numbers of centrifuges needed are based on these estimates that were made for Iran’s program in 2010, which suggest that a system of 48,000 centrifuges could produce 2500 kg of low enriched uranium (LEU) per month. LEU is around 5% U-235. Also, getting to LEU is most of the work of getting to higher enrichment levels since you need fewer centrifuges at each stage. Thus, I estimate that a large project could produce 2500 × .05 kg = 125 kg of U-235 per 50,000 centrifuge months. Thus, operating 1000 centrifuges would net 125 / 50 = 2.5 kg per month. If you repeat that for two years, that gets you 60 kg.

- My estimate for the amount of ocean water you’d need to process to get the necessary uranium.

- You need 7429 kg of uranium.

- Seawater is 0.00000033% uranium, so you need 1 / (0.000000003) = 3.03e8 kg of seawater to get 1 kg of uranium.

- Thus you need a total of 7429 × 3.03e8 kg = 2.250987e12 kg of seawater.

- Water is 1000 kg / m³.

- So that is 2.250987e12 kg of water × (1 m³ water / 1000 kg water) = 2.250987e9 m³ water.

- 2.250987e9 m³ = (1310.6 m)³ = 1.3106 km³

- weight of water in swimming pool: 3742500 kg

- 2.250987e12 kg water × (1 swimming pool / 3742500 kg water) = 601,466.13 swimming pools

- Edit: I may have unconsciously stolen the last line from Nick Bostrom’s excellent (and frightening) paper, The Vulnerable World Hypothesis.