When you shift from being managed to also sometimes managing others, you have a predictable shift in perspective and a lot of obvious-in-retrospect insights. In the spirit of “saying obvious things is good” here are a few.

Be honest

Since you’re a fallible human, you will screw things up. And when you do, you’ll be tempted to mislead and cast blame elsewhere. Resist.

Say you were supposed to get some specs from the Halifax team but you forgot and now they’re all on vacation for a week. You could make up some story about some technical snafu like emails getting lost, and this might work. But:

- People are smart and will figure you out over time.

- Getting away with a lie gives you a temporary benefit. Getting caught means you will be trusted less forever.

- Lying works less than it appears to. Usually, your manager won’t have conclusive proof or just won’t feel like having a giant confrontation, so they won’t say anything. But they will remember.

- When you give an excuse, your manager will wonder—are you making it up? Why? How can they prevent that in the future? This greatly multiplies how much time they spend thinking about your mistake. It’s amazingly hard to be angry with someone who just says, “Sorry, I forgot”.

Of course, sometimes you really will hit weird issues, and when you do you should explain them. But your manager knows the base rate. They know that people who are “unlucky” a lot tend to be “unlucky” in the future.

Be straightforward

Say you recently worked on a project with Alice, during which Alice was annoying and incompetent and stole all the credit for your work. Now, your manager assigns you to work on another project with Alice. What should you do?

People often try to look for clever “schemes” for these kinds of situations. My advice is: Don’t scheme. Be diplomatic, but just ask for what you want and give the real reason that you want it. Perhaps, “I’d prefer not to work with Alice again. There’s a bit of a personality clash and I had trouble getting proper credit.”

Why? Well, what would you want if you were a manager? You’d want to have full information so you can make a fully-informed decision. If you present a problem other than the real one, then most likely it won’t make sense and your manager will be confused. And even if they accept it, it’s likely to have some solution that doesn’t address your real problem.

Just ask for what you want. A good manager will appreciate you not making them to waste their time trying to read your mind.

Of course, you may not always get what you want. When this happens, it’s a good opportunity to show your character by staying positive.

Be a joy to work with

Would you rather manage: a brilliant workaholic asshole or a decently smart and decently hardworking person who in every interaction was a little burst of sunshine?

Many things earn their status as cliches by being profound but neglected truths. This is one of them: You can be successful by being super-competent or super-pleasant, but the latter is easier.

I know this sounds kind of cynical. But I don’t look at it that way. For one thing, you don’t need some magical magnetic personality. If you just make a reasonable effort to be honest, stay positive, and follow up on what you’re asked to do, you’ll be above average. (Most people don’t really try!)

Also, picture one organization filled with brilliant workaholic assholes and another filled with pretty-smart pretty-positive team players. Which will do better? I guess it depends. But it’s a real question!

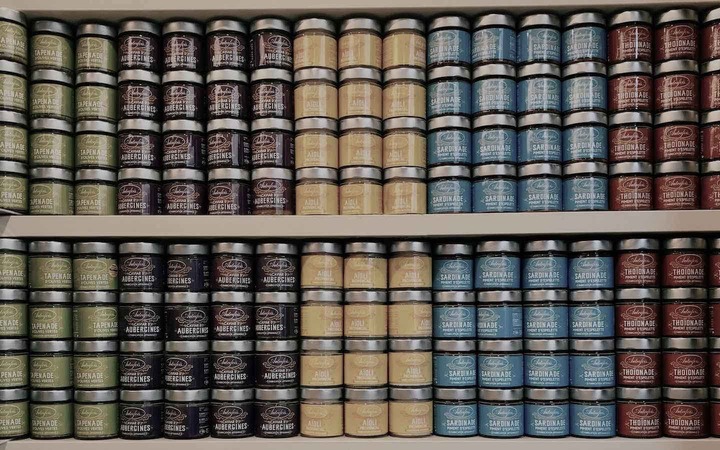

At a minimum, being a joy to work with creates tons of value for everyone you interact with. It makes sense for organizations to spend money on this for the same reason they spend money on swanky offices or good food for lunch. Working with people who spark joy is the ultimate perk.

Manager quality matters

I’m not sure how to operationalize this, but some managers are simply much better than others, in a way that has big implications for you and your future.

Remember why managers exist

The idea of market economies is that price signals create incentives and emergent structures that centralized planning could never match. So then why, inside market economies, do we have these giant command-and-control organizations like companies? There are various theories.

But common sense says that managers exist because (1) most of us need a supportive environment to be even moderately productive, (2) many things are best done by large groups of people, and (3) large groups of people are hard to coordinate. So, in an ideal world, managers would have these duties:

- Understand what their managees are doing.

- Understand how those activities contribute value to the organization.

- Communicate to managees how to create more value.

- Create incentives for managees to create more value.

This gives a heuristic for how to behave in all interactions with a manager: If in doubt, try to help them understand what you’re doing and try to learn how you can create more value.

It’s hard for your manager to understand what is happening on the ground

Giant Pacific octopuses have around 500 million neurons, with 30% in the central brain and the other 70% divided among the 8 arms. Some claim this gives them a distributed intelligence—the central brain can say, “arm five, go grab that gastropod!” but the arm may or may not obey. The brain isn’t even exactly sure where the arms are out in space.

Why organize a nervous system like this? One theory is that it’s because each arm gathers so much sensory information. It would be expensive and slow to send it all back to the central brain for decision-making. (There’s a reason your eyes are right next to your brain.) So instead, arms can quickly make local decisions like, “That’s not a gastropod and I’m not grabbing it.”

Human organizations are similar. Your manager has no magical way of guessing that you’re getting slowed down by poor-quality reagents or some passive-aggressive person in IT unless you tell them. And they can never understand the full texture of your experiences.

Really, human organizations are worse than an octopus, because your manager also needs to communicate with their manager, and so on. A better analogy would be a “recursive octopus” where arms have mini-brains and branching sub-arms.

I think a lot of the waste and inefficiency in large organizations happens just because the people making decisions don’t fully understand the impact of those decisions. Given this, one of your fundamental jobs is to communicate the reality to your manager. This hard. To get good at it, you need to take it seriously and practice it, just like any other skill.

Your manager is also being managed

Sometimes your manager won’t understand what you are doing, or won’t correctly combine that with global information, and so will force you to do dumb things. You’ll need to accept some degree of overhead as the cost of being part of a large organization.

Also, remember your manager’s manager will sometimes force them to dumb things. When that happens, it puts your manager in an awkward spot. They’re forced to give you instructions that they know are stupid, but they (probably) aren’t going to just tell you, “I know this is stupid but the CEO won’t listen.” Instead, they’ll say something vague like “this is the direction the company has decided on” and try to avoid further discussion. If you watch for these conversations, you can spot them easily.

A good manager will appreciate vigorous internal debate

If you disagree with something, it’s good to discuss it. A good manager will not just tolerate but encourage this under the right conditions.

After all, you’d naively expect managers to want debate since it should increase their chances of making the best decision. So why don’t they? I think because:

- Some managers are just insecure.

- Sometimes, they worry that debate means people won’t respect the final decision.

- Sometimes people debate things too long, at the wrong time, or in the wrong way.

You can address these concerns and create a pro-debate environment. Make sure:

- Your manager trusts that once the debate is over, you will be on board with the final plan and will try to make it work.

- You’re nice about how you bring it up and sensitive to when debate should happen and when it should end.

Try to be a little ruthless

Your organization (probably) isn’t a family, it’s a temporary alliance. Your manager is not nobility. You’re just two people who’ve temporarily banded together because it benefits both of you.

What I mean is: Try not to get upset about minor social niceties. If your manager says, “draft was poor, clarify paragraphs 2,3,7, and 14 ASAP”, try to not get obsessed about the tone and just clarify the damn paragraphs.

A century from now when everyone is dead, you’ll feel silly for getting upset about minor things. Try to interpret communication as signals for how you can create more value (for yourself and the organization).

Don’t be naive

There’s an inherent tension between incentives and flexibility. If a big company had no reporting requirements and told everyone to just do what they think was best, lots of people would decide that the best thing was to drink margaritas and watch Cheers re-runs.

So you need to be realistic about how your organization works—if you’re required to spend 25% of your time on non-value-creating activities to make sure you get promoted, you should either accept that or get another job. I think most places will have a reasonably high overhead here (although I wonder about the exact number).

This overhead is particularly frustrating for people who are motivated enough that it’s just wasting time that they otherwise would have spent working hard. If you are such a person, I’m not sure what you can do other than find a different organization that doesn’t need as much reporting. That might be because it’s tiny and everyone knows what everyone else is doing. Or it might be true because they’re somehow able to filter for people like you.

Managers are fallible hairless apes just like you

Often, they are people like you who got promoted and are doing their best but don’t particularly know what they’re doing. If they’re a little short-tempered one day, maybe it’s because their kid ate a box of crayons and was up sick all night.

There’s no fixing a bad manager

Or, at least, it’s not your job to fix a bad manager. All the above advice is assuming your manager is good or at least has good intentions.

I’m all for empathy, but you shouldn’t tolerate abuse. And if you have a manager that just flat-out gives you ridiculous instructions and won’t listen to you when you point out the problems, then you don’t have a lot of good options other than trying to get a different manager or finding a new job.