Here are two things that seem to be true:

- Homosexuality has a significant genetic component.

- Most pre-enlightenment cultures had norms against homosexuality.

Huh? Genetic evolution kept the genes associated with homosexuality around, suggesting those genes don’t hurt reproductive fitness. Yet, cultural evolution favors norms against homosexuality. Why would two different types of evolution come to different conclusions?

While this seems paradoxical at first, I think these trends may actually reinforce each other.

More broadly, this is a good case study: Say you’re a sentient being that was formed by evolutionary processes. What do those processes want, and what should you think about that?

Let’s start with the evidence for the two claims.

Homosexuality has a significant genetic component

Twin studies

The classic way to estimate heritability is twin studies. For homosexuality, some early studies got high numbers, but I don’t trust them because they used small samples with massive opportunities for sample bias.

The best twin study was done by Långström et al. (2010) who surveyed every adult twin in Sweden that was 20-47 years old in 2005. They asked them if they had at least one same-sex sexual partner (SSSP) in their lifetime, and checked if twins tended to give the same answer:

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall population | 5.6% | 7.8% |

| Fraternal twin w/ SSSP | 11% | 17% |

| Identical twin w/ SSSP | 18% | 22% |

This table is confusing, so let me explain. The first row just shows that overall, 5.6% of men and 7.8% of women report an SSSP. The second row shows that if you take a male with an SSSP and a male fraternal twin, that twin will also report an SSSP 11% of the time. The last row is the same thing but with identical twins.

If homosexuality were completely random, the numbers in each column would all be the same. Instead, the more closely related people are, the more likely they gave the same answer.

Now, you might imagine that this could be due to how people were raised. So, they try to decompose the contributions of different factors. Bearing in mind that heritability is a weird concept, here is what they find:

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic | 39% | 19% |

| Shared environment | 0% | 17% |

| Unique environment | 61% | 64% |

For males, this is similar to the heritability of common personality traits, typically around 40%. For females—for unclear reasons—the influence of genetics is lower and the influence of shared environment is higher.

They do a similar analysis looking at the total number of same-sex sexual partners someone has had in their life, with similar results.

GWAS

The hip new alternative to twin studies is the genome-wide association study (GWAS) where you sequence the entire genomes of a bunch of people and look for associations between specific genes and outcomes. A huge study was done by Ganna et al. (2019) who took around 500k people aged 40-70 mostly from the UK Biobank and a few people from data collected by 23andMe.

First of all, they ignored the genetic data and just computed heritability estimates by looking at how closely related people are. Their heritability numbers look very similar to common personality traits:

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic | 37.1 | 46.6 |

| Shared environment | 0 | 2.9 |

| Unique environment | 62.9 | 50.5 |

They then looked at the genetic data. They found five variants (single “letter” changes in the genetic code) that had statistically significant associations with having at least one SSSP in one’s lifetime. One of the variants might be associated with cigarette smoking. A different one might be related to sex-hormone sensitivity and male pattern baldness. A third one seems to be related to the sense of smell. (Some of these are for women and men combined and some are for one sex only.)

Each of the individual genes had a relatively small contribution to same-sex sexual behavior, usually changing the odds by a factor of 1.1 or so. So there’s no “gay gene” but rather many genes, each of which makes a modest change to the odds that someone is gay.

There are surely many other relevant genes that this study didn’t find. Dozens look related but didn’t rise above the significance threshold due to the sample size. (When you look at the entire genome you have a huge risk of false discoveries, so you have to set discovery thresholds very tight. This means that what you find is probably real but you easily miss stuff.)

Using all the data they find an SNP heritability of 8-25%, depending on the statistical method. SNP heritability is almost always lower than what you get from family studies for reasons that are still debated. (I think it’s because SNP heritability usually only captures additive effects (and maybe dominance effects) but not epistatic interactions, but what do I know?)

Most pre-enlightenment cultures had norms against homosexuality

Is there any way to talk about “most” cultures without falling into a pit of sample bias and confirmation bias?

Actually, yes. Anthropologists are smart. In 1969, Murdock and White designed the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample, a pre-determined set of 186 cultures around the world that are relatively genetically and culturally independent of each other.

In 1976, Broude and Greene determined sexual practices in as many of these cultures as possible. Unfortunately, they were only able to figure things out for a minority, but this is still reasonable evidence if we believe that the cultures are independent.

Here were the attitudes they found towards homosexuality in 42 societies:

| Attitude | Percentage of cultures |

|---|---|

| Accepted or ignored | 21.4% |

| No concept of homosexuality | 11.9% |

| Ridiculed but not punished | 14.3% |

| Disapproved but not punished | 11.9% |

| Strongly disapproved and punished | 40.5% |

And here is how common homosexuality was in 70 cultures:

| Prevalence | Percentage of cultures |

|---|---|

| Present / not uncommon | 41.4% |

| Absent / rare | 58.6% |

The way I read this is that between 2/3 and 4/5 of cultures have norms against homosexuality and that these are strong enough that in more than half of places, homosexuality barely seems to exist.

And lest you think that most cultures are just uniformly conservative about sex in every way, consider the numbers for premarital sex (in 114 cultures):

| Prevalence | For men | For women |

|---|---|---|

| Universal | 59.8% | 49.1% |

| Moderate | 17.8% | 16.7% |

| Occasional | 10.3% | 14.0% |

| Uncommon | 12.1% | 20.2% |

Around ⅓ of places had universal premarital sex but no homosexuality.

I was interested, so I found the 53 cultures where data on both homosexuality and premarital sex were available. (I randomly used premarital sex for women.) There’s less dependence than you might expect between the two norms.

| Premarital sex \ homosexuality | Present | Absent |

|---|---|---|

| Universal | 11.3% | 32.1% |

| Moderate | 9.4% | 7.5% |

| Occasional | 7.5% | 13.2% |

| Uncommon | 9.4% | 9.4% |

The most common pattern was to have universal premarital sex but no homosexuality. The unusual cultures in the lower-left with homosexuality but little premarital sex are:

Homosexuality might be more common in agricultural societies than hunter/gatherer societies.

In 2009, Rebecca Kyle compared these societies by the level of population pressure they were under: low (hunting/gathering) medium, or high (intensive agriculture). She found that homosexuality was more common with more population pressure.

This was apparently an undergraduate research project. In 2016, Apostolou did pretty much the same thing (but didn’t cite Kyle).

Why evolution did this

Having established those claims, let’s return to our original question: How could both of these things happen at the same time?

- The genes associated with homosexuality persist, suggesting they help reproductive fitness.

- The norms to punish homosexuality persist, suggesting they also help reproductive fitness.

Is this a contradiction? Let’s think about how evolution works for each of these.

How could genes that cause homosexuality survive?

People often throw around cute little evolutionary stories. Some people suggest that being gay allows low-status males to reproduce. (Something like: If the king wants you to hang around for gay sex, maybe you can secretly impregnate the occasional courtesan.) Others suggest that “gay uncles” might increase the fitness of their nieces and nephews so much that it’s advantageous.

I doubt it. Partly, that’s because I don’t think these stories make much sense. For example, how many kids do homosexuals have? Our friends who did the GWAS above (Ganna et al.) find the numbers for the UK Biobank data (which I had to guess from a plot):

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 75% opposite sex partners | ~1.6 | ~1.5 |

| ≥ 75% same sex partners | ~0.6 | ~0.4 |

At least in modern society, people who have sex with people of the same sex have many fewer kids. There’s no way that helping to take care of your siblings’ children would make up for this.

Beyond being implausible, I think these stories have a deeper problem: They are trying to explain something that doesn’t need to be explained.

Let’s back up. Evolution is not about the fitness of individuals, it is about the fitness of genes. Just because a gene sticks around for a long time does not mean that everything that gene does is good.

Genes do lots of things. For example, Ganna et al. found genetic correlations between homosexuality and various other traits. Roughly speaking, this is the part of the correlation that is due to genes and not environmental factors.

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Cannabis use | 0.308 | 0.671 |

| Number of sexual partners | 0.407 | 0.681 |

| 2D:4D finger ratio | 0.237 | 0.002 |

| Major depression | 0.328 | 0.438 |

| Openness to experience | 0.135 | 0.312 |

| Height | -0.075 | -0.043 |

You should be skeptical of these exact numbers, but you get the point. Genes have many effects.

The above numbers come from combining the UK Biobank and 23andMe data. They also show separate estimates from each of these datasets alone and get quite variable results. For example, the genetic correlation between SSSP and cannabis use for men was 0.45 on the UK Biobank data but only 0.09 on the 23andMe data.

For a gene to be fit just means that when averaged over many people, the gene is helpful. I’m sure that there are genes that make it more likely for people to become celibate monks or sacrifice their life for others at the age of 18. That doesn’t mean those behaviors help those people pass on their genes.

So, just because genes associated with homosexuality persist does not mean that homosexuals must have equal reproductive fitness! Instead, it could just be that these genes increase fitness in heterosexuals.

Here are two simple models of how this might work.

Model 1. Say there is a single “gay gene”. People without the gene are never gay, and people with the gene are gay 1/3 of the time. People have these numbers of kids:

- Regular gene: 2 kids

- Gay gene and gay: 0 kids

- Gay gene but not gay: 3 kids

Even though gay people have no kids, the “gay gene” will reproduce itself just as well.

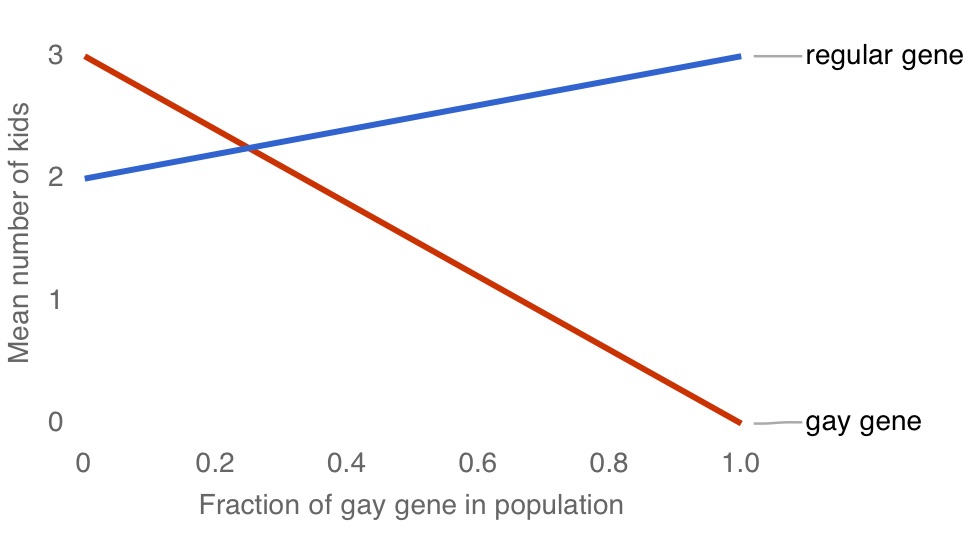

Model 2. Say again that there’s a “gay gene” and that each person can have 0, 1, or 2 copies. (If you’re a biologist, insert “diploid”, “locus”, and “allele” into the previous sentence.) People with 2 copies of the gene are only attracted to the same sex and have no kids. But people with a single copy of the gene are heterosexual and have more kids:

- No gay gene: 2 kids

- 1 gay gene: 3 kids

- 2 gay genes: 0 kids

If people mate at random, there is an equilibrium where 25% of genes in the population are the gay version. (If it's less than 25%, the gene will spread, and if it's more than 25% it will become less common.)

Suppose that a fraction x of genes in the population are the gay gene and that people mate at random. You can show that if x<1/4 the gay gene will lead to more kids on average, while if x>1/4, the opposite will happen. The unique equilibrium is x=1/4, where the gay gene will have equal reproductive fitness.

What will happen? Suppose that a fraction x of the genes in the population are the gay version, and that people mate at random. (Biologists: “Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium”) Now, go through all the genes in all the people in the world and pick a random gay gene. How many offspring will that gene result in? There’s a (1-x) chance that the other gene is regular meaning 3 kids, and a x chance the other gene is gay, meaning 0 kids. So, averaged over all the gay genes in the world, the mean number of kids is

3(1-x).

Meanwhile, take a regular gene. There’s a chance (1-x) that it gets matched with another regular gene meaning 2 kids, and an x change it gets matched with a gay gene, meaning 3 kids. So the average number of kids for all the non-gay genes in the world is

2(1-x) + 3x.

Here’s what this looks like:

If x is small, gay genes will reproduce better than non-gay genes and x will increase. If x is large gay genes will reproduce worse and x will decrease. The equilibrium is at x=1/4 where both of the above equations evaluate to 2.25. That will be stable even though, in this model, gay people never have any children.

Again, we know there is no single gay gene. A better model would be that there’s lots of different genes that marginally change the probability of being gay. But the same basic dynamics are still possible.

While this second model is an oversimplification of homosexuality, it’s a pretty good model of how carriers of a single copy of rs334 have a greater resistance to malaria but carriers of two copies get sickle cell disease. This means that in sub-Saharan Africa—where malaria poses the greatest threat—there’s an equilibrium with 10-40% of people carrying the gene.

No one looks for “explanations” of how sickle cell disease enhances fitness. It doesn’t. But the gene that causes it is fit because people with a single copy do even better than people with zero.

Now if an analogy between homosexuality and a horrible inherited blood disorder makes you cringe, well, me too. But this brings up a very important point: Evolution doesn’t care about the difference in how these things affect life quality because evolution only sees reproduction. We’ll come back to this.

There’s some evidence that female relatives of gay men have, on average, more children than female relatives of straight men (Camperio-Ciani et al., 2004, Camperio Ciani et al., 2008, Camperio Ciani et al., 2012), though so far this research all seems to come from one research group with relatively small samples.

How could a culture evolve a norm against homosexuality?

Again, complicated stories float around. For example, maybe societies that prohibit homosexuality are better at war, so the societies that randomly prohibited homosexuality thousands of years ago dominated everyone else until most of the tolerant cultures either adopted the norms or died off.

I don’t buy this. The problem is that this is a story of group selection and group selection is almost always wrong.

Just imagine: Suppose punishing homosexuality made you better at war, but tolerating homosexuality meant you had more kids. Then in a culture that prohibited homosexuality, you’d see all sorts of families and subcultures “defecting” by being tolerant. It wouldn’t be a stable norm.

No, if cultural evolution results in punishing homosexuality, that’s got to be because it benefits reproductive fitness for individuals.

How would that happen? This seems… totally obvious? If my religion says homosexuality is wrong, then gay people in my religion will be more likely to pretend to be straight and have kids. At an individual level, prohibiting homosexuality increases reproductive fitness.

I think it’s that simple. Prohibiting homosexuality is an indirect way of making people breed more. Yes, it probably makes the same people it “helps” unhappy but again, evolution doesn’t care about that.

Us

Having fleshed out why genetic evolution and cultural evolution did what they did, is there a conflict?

No. These trends are completely compatible. The genes for homosexuality probably persist not because they cause homosexuality per se but because of other effects in other contexts. And cultural prohibitions on homosexuality persist because they lead to more kids. Neither interferes with the other.

In fact, these two trends probably enhance each other: In a culture that prohibits being gay, the “negative” effects of the genes that cause homosexuality will be reduced, i.e. more gay people will breed because they were forced to pretend to be straight. But the “positive” effects of those genes, whatever they are, are probably just the same.

Under this theory, tolerant societies would tend to have fewer genes associated with homosexuality, whereas Iran would tend to have more. (Speculative)

Possible conclusions

When thinking about this stuff, people often seem to draw two different conclusions:

- Since genetic evolution selected genes associated with homosexuality, it is natural and good.

- Since cultural evolution selected norms that discourage homosexuality, it is bad.

Which is right?

Neither. The only sensible conclusion is: To hell with evolution.

What do you care about evolution? It certainly doesn’t care about you. It created parasites and cancer and sickle cell and the black death and antisocial personality disorder. It designed us so that after we reproduce and raise our kids, our bodies sort of fail in every way at the same time. The fact that evolution did something doesn’t mean you’re supposed to like it.

Evolution isn’t even about you. You are a complex assembly of molecules. It’s tempting to think of genetic evolution as a war between individuals to reproduce, but that’s not right. It’s a war between genes. If a gene can spread by making the organism more fit, that’s just incidental.

Around 42% of your genes are retrotransposons, little bits of DNA that might cause genetic diseases or cancer, but exist simply because they figured out how to copy and paste themselves around the genome. You are not a participant in the war of evolution, you are part of the battlefield.

The same thing is true for cultural evolution. A culture is a set of ideas or—in Dawkins’ original sense—memes. The memes that survive are those that spread. Sometimes memes spread because they help the people who hold them reproduce, but that’s again incidental. Lots of bad medical advice can be thought of as memes that harm their hosts to spread themselves.

And even for genes and memes that are helpful to the reproduction of their host, so what? Reproduction is not the same thing as being happy.

Evolution created genes that cause homosexuality, then created norms to punish homosexuality. This created lots of pain, but evolution doesn’t mind. If this shows anything, it’s that evolution is a jerk.

What to want

There’s no right answer for what to want. Me, I want the typical “sentient beings explore the limits of time/space/art/understanding/qualia”. While I recognize that I want those things because evolution made me that way, I want them all the same and they aren’t the same as just serving the genes and memes that created me.

And personally, if I see why a norm evolved, and I don’t care about the goals that norm is serving, and that norm is interfering with other goals I do have (like people being happy), then I favor dropping that norm, duh.

Of course, we can’t simply ignore evolution, because it won’t ignore us. You might worry that if you discard a norm that cultural evolution likes, it won’t work. Some subcultures would still maintain it and maybe they will have more descendants and slowly take over.

I reluctantly admit that’s possible, or at least it was in pre-historical tribal bands. But still:

- Are you sure it won’t work? Most of our norms evolved a long time ago. It’s not obvious which ones still have an advantage in late modernity.

- Even if you are sure, why respond by preemptively capitulating? That’s very strange logic! If we discovered that infant exposure enhanced reproductive fitness, surely we wouldn’t bring that back.

- If you’re worried about low fertility, well, have you noticed that fertility is dropping among basically everyone everywhere? I don’t know exactly what’s causing this, but I guess it’s (a) birth control exists and (b) people feel the cost/difficulty of kids outweighs the benefits. If we want to increase fertility, maybe we should work on the old cost/benefit ratio?