1.

Say we’re detectives. We’re getting a drink and have the following conversation:

Me: Ah, this case is killing me.

You: Then why don’t you go talk to Big Eddie?

Me: Nah—that would do more harm than good.

You: How’s that?

Me: Well, we all know Big Eddie often lies.

You: Yeah, sure, but sometimes he’s helpful.

Me: If I went to talk to him, he’d probably lie. And probably it would be impossible to check his story without spending huge amounts of time and exposing myself to danger. But I’d feel obligated to do it anyway, and while I was distracted, the true criminal would get away. That risk outweighs the chance that he’d give me something useful.

You: But why not…

Me: Look, you agree the expected value of talking to Eddie is negative, right?

You: Yes, except…

Me: Come on, be rational!

2.

What’s wrong with my reasoning above?

The rational thing would be to talk to Eddie, and then check out his story if that’s easy. Instead, I’m just accepting that I’ll always check out his story—even when that’s stupid—and compensating by refusing to listen to the story in the first place.

This is what happens when you optimize one component of a system while another component is suboptimal.

3.

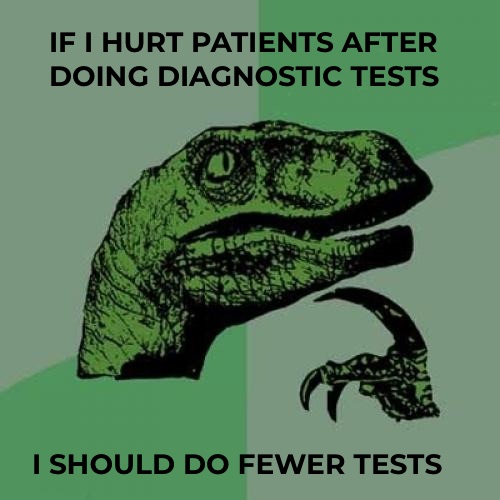

So, there’s a movement in medicine that some diagnostic tests shouldn’t be done. Partly, the goal is to stop wasting money on useless tests. As a fan of using resources in ways that improve human welfare, I say that’s great.

But there’s another motivation—that sometimes doing diagnostics leads to worse health outcomes. (There’s a whole series in JAMA with stories like these.)

Example 1: Deborah Korenstein tells this story:

I know of a completely healthy older woman living in New York whose primary care doctor did a chest X-ray. It’s not clear why he did this as she had no symptoms. The X-ray showed a nodule on her lung, so they did a PET scan, which showed the same nodule. They were worried about lung cancer, so they did a bronchoscopy. Something went wrong, and it caused severe hoarseness that required her to stop talking for weeks and to go to speech therapy.

They were still concerned about cancer, so they took a biopsy, which required an incision in her chest. It tested negative for cancer, but they were worried it might be tuberculosis, so they kept her in isolation over a period of weeks. It was negative for that as well. So because of the chest X-ray, this woman had multiple tests, a piece of her lung taken out, all this anxiety, and terrible hoarseness that needed treatment, and none of it benefited her in any way.

Example 2: Ruzieh (2020) describes a patient in their 70s who was up for a kidney transplant but otherwise in good health. For no particular reason, doctors decided to run a heart health test that revealed narrow arteries. This led to an escalating series of procedures and ultimately emergency heart surgery, pneumonia, and 10 days in the hospital. In the end, the patient’s cardio health was worse than when it all started.

He comments:

Although these tests are obtained with the best of intentions and done in concordance with current standards of care, this practice increases health care costs without clear improvement in patient outcomes. Importantly, it is also associated with downstream procedural harms and delays of needed care.

Example 3: Mandoori et al. (2017) describe a patient who had smoked 20 years previously who was nervous about lung cancer, and so asked her doctor to do a low-dose CT scan. She had no symptoms and was at low statistical risk. The scan showed some small lung nodules, while a second scan three months later also showed a 3.2 cm lesion. This led to a PET scan that showed no small nodules but confirmed the lesion. Doctors considered surgery but decided against it because the lesion seemed to be growing too fast to be lung cancer. One month later, the lesion had shrunk, suggesting it was just some kind of inflammation or infection.

They say:

Risk perception and maximalist approaches to lung cancer screening can result in both overdiagnosis and overtreatment. This presents real danger to patients, given the risks of pulmonary nodule evaluation that include patient anxiety, additional radiation exposure, bronchoscopic and percutaneous biopsy attempts, and surgery.

Basically, if you’re a doctor and you order CT scans for low-risk patients, you could hurt them by:

- Exposing them to radiation in the CT scan itself.

- Causing anxiety via a positive result.

- Running a tube down their throat or putting a needle through their chest to do a biopsy on something found via the CT scan.

- Performing a dangerous surgery to remove something that was found via the CT scan.

4.

Now, I’m sure the above advice is sound. These are real problems and people are hurt by being over-treated.

But can we also acknowledge that this situation is completely insane?

Some of the above reasons to be careful about testing are fine. By all means, account for the costs of the CT scan itself (#1). And I’ll wearily pretend to accept that people are emotional and couldn’t understand Bayesian reasoning or false positives and so we need to worry about stressing them out (#2).

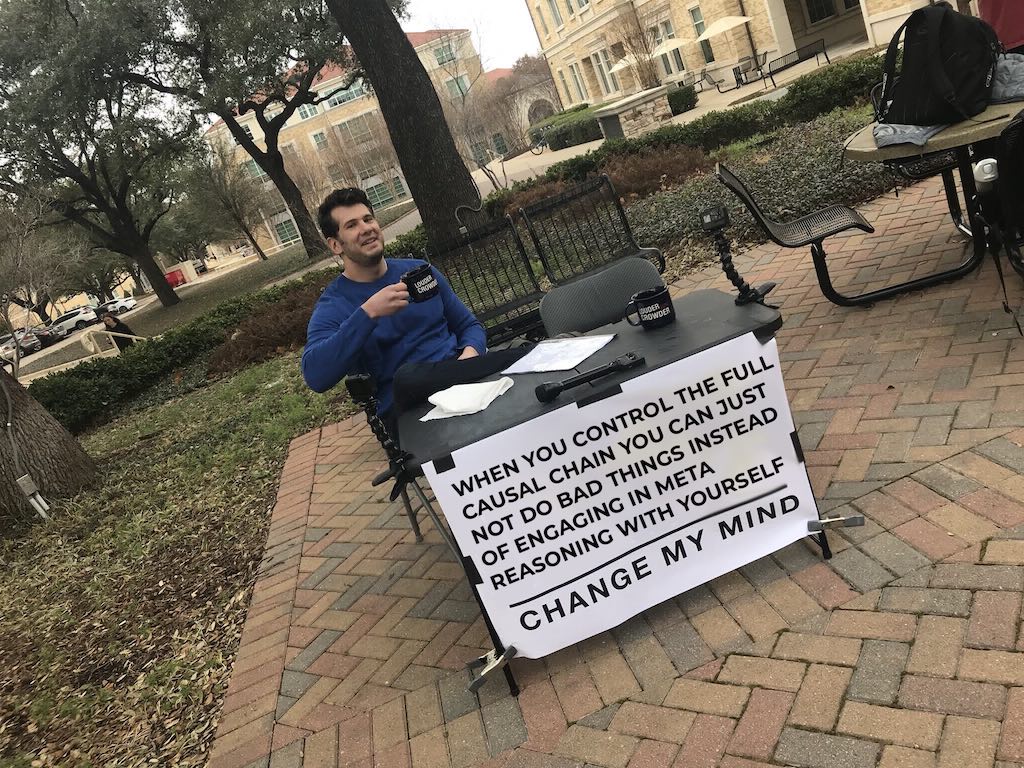

Fine. But let’s think about the other reasons. The logic of #3 seems to be this:

- If you do a CT scan and it shows a mass, you’ll order a biopsy.

- But because that patient was low-risk, the harms of that biopsy will outweigh the benefits.

- Thus, you shouldn’t do the CT scan.

What? If the harms of the biopsy outweigh the benefits, don’t do the damn biopsy! Why are we taking as given that a net-negative decision to do a biopsy will be made, and solving that problem by trying to prevent the opportunity to make that bad decision?

If you know that a patient’s prior probability for a condition is low, you still know that after doing a test. In a sane world, wouldn’t you do the CT scan, and then… only do the biopsy only if the CT scan showed something serious enough to justify the risks?

The suggestion is that once the test is done and you’re looking at the results, you will inevitably neglect the prior probability. Thus, you should avoid doing tests where disregarding the prior leads to bad outcomes. In other words, “If I gather some data, I will disregard the base rate. So, I won’t gather any data.”

I’m not sure if this phenomena has a name. Maybe “base rate avoidance disorder”?

Now, I can sort of understand this kind of thinking when you can order the test, but further choices are out of your hands. Maybe you’re convinced that the patient or other doctors will irrationally insist on harmful treatments. But there’s eerily little reflection on the possibility that the mistake might be somewhere other than the initial test.

It’s a fact that if you make decisions correctly, then putting more information into the system can’t hurt you. Or in case you’d be impressed by seeing that sentence turned into an equation: Say Y is a random unknown quantity (e.g. if someone has cancer), a is the action/choice you can make (e.g. if you do a biopsy or not), and utility(a,Y) is how happy you are to have done a if the value was Y. If X is some observed quantity that is related to Y (e.g. a CT scan) then

maxₐ 𝔼[utility(a,Y)] ≤ 𝔼[ maxₐ 𝔼[utility(a,Y)|X]].

It can only help you to know X! But what do I know, maybe medicine has some counterintuitive dynamics (psychology? insurance? legal issues?) that mean you can’t hope to make optimal choices.