The Monty Hall problem has now been a pox on humanity for two generations, diverting perfectly good brains away from productive uses. Hoping to exacerbate this problem, some time ago I announced a new and more pernicious variant: What if you and Monty try to cheat?

Since then, many people have sent arguments. (Thank you!) Here, I’ll review the problem and then go over all the arguments people sent in.

Reminder

As a reminder, here’s the standard Monty Hall problem:

- There are 3 doors. A car is randomly placed behind one, and goats behind the other 2.

- You pick one door.

- Monty looks behind the other 2 doors. He chooses one of them with a goat behind it, and opens it.

- You get two options:

- Option A: You get whatever is behind the door you picked.

- Option B: You get whatever is behind the other closed door.

The well-known solution is that you should always switch, which gets you the car ⅔ of the time.

Variant

In our variant, Monty is corrupt. The night before the game, you show up at his house with a suitcase of cash. He agrees that he will follow whatever algorithm you want when choosing the door to open. (Of course, he still can’t open a door with a car.)

What makes this challenging is:

- Monty doesn’t know where the car will be before the show starts.

- After the show starts, Monty can’t communicate with you other than by choosing what door to open.

The problem is: What is the best strategy for you and Monty to use?

The naive solution would be to play as if there was no conspiracy: Monty would just pick a random door, and you would always switch. This would get you the car ⅔ of the time. The question is: Can you do better?

The answer

No.

Thanks to the dozens of people who sent in different arguments. (And my apologies for being so criminally slow in responding.) I read all of them in detail, tried to “cluster” similar proofs together, and then gave everything a consistent notation. (Because of this, many proofs are changed a fair bit from what folks originally sent in.)

The “without loss of generality” argument

The position of the car is randomized, so it doesn’t matter (on average) which door you choose at the start. To keep things simple, say you always choose door #1. Now, there are three cases:

- If the car is behind door #1, then Monty can open either door #2 or door #3.

- If the car is behind door #2, Monty must open door #3.

- If the car is behind door #3, Monty must open door #2.

Monty only has freedom when the car is behind door #1. Suppose without loss of generality that he always chooses to open door #2 in this case. Now, what happens?

- In ⅔ of cases, Monty will end up opening door #2, and in ⅓ of cases, he will open door #3.

- If Monty opens door #2, there’s a 50/50 chance the car is behind door #1 or door #3. It doesn’t matter if you switch or stay. Either way, you have a ½ chance of winning.

- If Monty opens door #3, there is a 100% chance the car is behind door #3, so you should always switch.

If you always switch when Monty opens door #3, then your overall chances of winning are

ℙ[Win]

= ℙ[Monty=2] ℙ[Win | Monty=2]

+ ℙ[Monty=3] ℙ[Win | Monty=3]

= ⅔ × ½ + ⅓ × 1

= ⅔.

Since this is the optimal strategy, ⅔ is as good as you can do.

Why you might not like this argument: It assumes that Monty always does the same thing in the same situation. Maybe you could do better if he used a randomized strategy?

Credit: Unheamy, Alan, Matt, Dan Sisan, Steven, ExistentAndUnique, heelspider.

The information argument

If you had no information at all, your odds would be ⅓. But when Monty opens a door, he has only two options, so can convey at most one bit of information. But one bit of information can at most double your odds. So you can’t do better than ⅔.

Why you might not like this argument: Why can one bit of information at most double your odds? And anyway, does Monty really convey a full bit of information, given that in ⅔ of cases, he has no choice about which door he opens?

Credit: KingLewi

The decision points argument

Assume without loss of generality that the player picks door 1. Now, if the player picked the wrong door, Monty has no choice, there is only one other door with a goat, which he must open. So the only decision points are:

- If the car is behind door #1, should Monty open door #2 or door #3?

- If Monty opens door #2, should the player switch?

- If Monty opens door #3, should the player switch?

Suppose that when Monty has a choice, he opens door 2 with probability p and door 3 with probability 1-p.

Note for reference that

ℙ[Monty=2]

= ℙ[Car=1] × p + ℙ[Car=3]

= ⅓ × p + ⅓

= ⅓ × (p+1).

And similarly,

ℙ[Monty=3]

= ℙ[Car=1] × (1-p) + ℙ[Car=2]

= ⅓ × (1-p) + ⅓

= ⅓ × (2-p)

Now, suppose the player sees that door #2 is open. Then, the player knows that

ℙ[Car=3 | Monty=2]

= ℙ[Car=3, Monty=2] / ℙ[Monty=2]

= (⅓) / (⅓ × (1+p))

= 1/(1+p)

≥ ½

Similarly,

ℙ[Car=2 | Monty=3]

= ℙ[Car=2, Monty=3] / ℙ[Monty=3]

= (⅓) / (⅓ × (2-p))

= 1/(2-p)

≥ ½.

Thus it is optimal for the player to always switch. But if you always switch, then it’s you get the car ⅔ of the time regardless of what Monty does. So you can’t do better than ⅔.

Why you might not like this argument: Maybe this feels too “Bayesian” for you? (Personally, I like this argument a lot.)

Credit: Joao, Beckett, Elvis Sikora, Isaac Grosof, Drake

The analogy argument

Consider a game, which I’ll call GAME 1:

- There are 3 doors. A car is randomly placed behind one, and goats behind the other 2.

- Monty looks behind all three doors. Then he can show you either a RED flag or a BLUE flag.

- You pick one door.

It’s “obvious” that you can win this game ⅔ of the time and no more.

Now consider GAME 2 (where I’ve highlighted the changes in bold).

- There are 3 doors. A car is randomly placed behind one, and goats behind the other 2.

- Monty looks behind all three doors. Then he can show you either a RED flag or a BLUE flag. However, if the car is behind door #2, he is not allowed to reveal the RED flag, and if the car is behind door #3, he is not allowed to reveal the BLUE flag.

- You pick one door.

Clearly, this is not easier than game 1, since the only difference is that Monty has less flexibility in choosing the flags. So you can win at most ⅔ of the time.

Now consider GAME 3:

- There are 3 doors. A car is randomly placed behind one, and goats behind the other 2.

- Monty looks behind all three doors. Then he can open either door #2 or door #3. However, he cannot open a door that has a car behind it.

- You pick one door.

This is equivalent to game 2. Opening door #2 is equivalent to showing a RED flag, while the opening door #3 is equivalent to showing a BLUE flag.

Finally, consider GAME 4:

- There are 3 doors. A car is randomly placed behind one, and goats behind the other 2.

- You pick one door.

- Monty looks behind all three doors. He then opens some door you did not pick. However, he cannot open a door that has a car behind it.

- You pick one door.

This is equivalent to game 3. If you pick door #1 in the second step, they are the same. But since the car is placed randomly, you might as well pick door #1 — choosing another door will not improve your odds.

Putting all of our logic above together, we get that

⅔

= (Optimal play in game 1)

≥ (Optimal play in game 2)

= (Optimal play in game 3)

= (Optimal play in game 4)

≥ ⅔,

and thus

(Optimal play in game 4) = ⅔.

But of course, game 4 is exactly the conspiratorial Monty Hall problem.

Why you might not like this argument: Is it really “obvious” that it’s not possible to win game 1 more often than ⅔ of the time?

Credit: I did it. I did it all, by myself.

The “more doors” argument

Suppose we had 100 doors rather than 3. Assume that Monty still opens a single door, and then are allowed to choose any door other than the one Monty opened (including your original door). What then?

An obvious strategy would be for Monty to open the door to the right of the true one whenever possible. For example, suppose there were ten doors (and you start by guessing door 1). Monty might use this table:

| Location of car | Monty opens |

|---|---|

| 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 5 |

| 5 | 6 |

| 6 | 7 |

| 7 | 8 |

| 8 | 9 |

| 9 | 10 |

| 10 | ??? |

Once Monty opens the door, you know where the car is—unless the car happens to be behind door #10.

See the problem? There are 10 possible locations for the car, but in any given situation, Monty only has (at most) 9 signals he can send you. No matter what number you and Monty decide to put in the “???” square above, there are going to be two locations on the left that get mapped to the same location on the right. That means, there’s always going to be one “unlucky” location, meaning your overall chances of getting the car are (N-1)/N.

(Of course, there are many other equivalent strategies — you can put any 9 of the numbers in {1, 2, …, 10} anywhere in the right column so long as the two numbers in the same row are different.)

Why you might like this argument: It’s very intuitive. And it shows an interesting difference: In the regular Monty Hall problem, your chances deteriorate when there are more doors, assuming Monty only opens one. But in this version, they get better. So it’s arguably a kind of coincidence that they coincide for N=3.

Why you might not like this argument: It’s not very formal. And what if Monty used some kind of randomized strategy?

Credit: Dan

The parameterization argument

Assume without loss of generality that you always start by picking door #1. Now, the only freedom Monty has is to choose which door to open. He can only exercise this freedom when you have in fact chosen the car. In this case, let p be the probability that Monty chooses to open door #2, and let (1-p) be the probability that Monty chooses to open door #3. This parameter completely encodes Monty’s part of the strategy.

Now, what about your part of the strategy? Well, all that you can choose is:

- Your probability of switching if Monty opens door #2. (Call this x)

- Your probability of switching if Monty opens door #3. (Call this y)

If you work out the probabilities, it turns out that your final win probability with this setup is

ℙ[win] = ⅓ (1 + (1 - p)x + py).

But note here: (1-p) is a positive number, and p is a positive number. (Technically these are “non-negative” since they could be zero.) Thus, your odds of winning are maximized by setting x=y=1. Then, you get that

ℙ[win] = ⅓ (1 + (1 - p) + p) = ⅔.

So, regardless of what Monty does, you should always switch, and then you’ll win ⅔ of the time.

Comment: Say that p=0, i.e. Monty always chooses door #2 when he has a choice. Then the probability of winning is ℙ[win] = ⅓ (1 + x). You can maximize this by choosing x=1, and any value for y. This means that if Monty always chooses door #2 when he can, it doesn’t matter what you do when Monty opens door #3.

Why you might not like this argument: “It turns out”

Credit: anonymous, John D., Michael Lucy

The parameterization argument, but actually doing the math

In general, your chances are

ℙ[Win]

= ℙ[Car=1] ℙ[Stay | Car=1]

+ ℙ[Car=2] ℙ[Switch | Car=2]

+ ℙ[Car=3] ℙ[Switch | Car=3]

= ⅓ ( ℙ[Stay | Car=1] + ℙ[Switch | Car=2] + ℙ[Switch | Car=3]),

where in the second line I use that the position of the car is randomized, so ℙ[Car=1] = ℙ[Car=2] = ℙ[Car=3] = ⅓.

Now, when you and Monty devise your strategy, what options do you have? First, let’s think about Monty’s strategy. He only has a choice to make when the goat is behind door 1. (If it is behind door 2, he must always open door 3. If it is behind door 3, he must always open door 2.) Let p be the probability that he opens door 2 in this case, and (1-p) the probability that he opens door 3.

Thus, here is the table of ℙ[monty | car] for each possible value of monty and car:

| Car=1 | Car=2 | Car=3 | |

| Monty=1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Monty=2 | p | 0 | 1 |

| Monty=3 | 1-p | 1 | 0 |

Now, let’s think about your part of the strategy. All that you will observe is Monty opening door 2 or door 3, and you can either choose to switch or to stay. Let x be the probability you switch if Monty opens door 2 and let y be the probability you switch if Monty opens door 3. Then here is a table of ℙ[Stay | monty] and ℙ[Switch | monty]:

| Monty=2 | Monty=3 | |

| Stay | 1-x | 1-y |

| Switch | x | y |

Now we can calculate the three probabilities we need in our above formula for ℙ[Win]:

ℙ[Stay | Car=1]

= ℙ[Monty=2 | Car=1] ℙ[Stay | Monty=2]

+ ℙ[Monty=3 | Car=1] ℙ[Stay | Monty=3]

= p (1-x) + (1-p) (1-y)

ℙ[Switch | Car=2]

= ℙ[Monty=2 | Car=2] ℙ[Switch | Monty=2]

+ ℙ[Monty=3 | Car=2] ℙ[Switch | Monty=3]

= 0 × x + 1 × y

= y

ℙ[Switch | Car=3]

= ℙ[Monty=2 | Car=3] ℙ[Switch | Monty=2]

+ ℙ[Monty=3 | Car=3] ℙ[Switch | Monty=3]

= 1 × x + 0 × y

= x

If we put these numbers into our win probability formula, we get

ℙ[Win]

= ⅓ ( ℙ[Stay | Car=1] + ℙ[Switch | Car=2] + ℙ[Switch | Car=3])

= ⅓ ( p (1-x) + (1-p) (1-y) + y + x)

= ⅓ (1 + (1 - p) x + p y)

Now, p and (1-p) are both positive (non-negative) numbers, meaning the best choice is x=y=1, for which ℙ[win]=⅔, regardless of the choice of p. Thus, it doesn’t matter what Monty does, you should always switch.

Why you might not like this argument: Lots of calculation.

Credit: Peter Donis

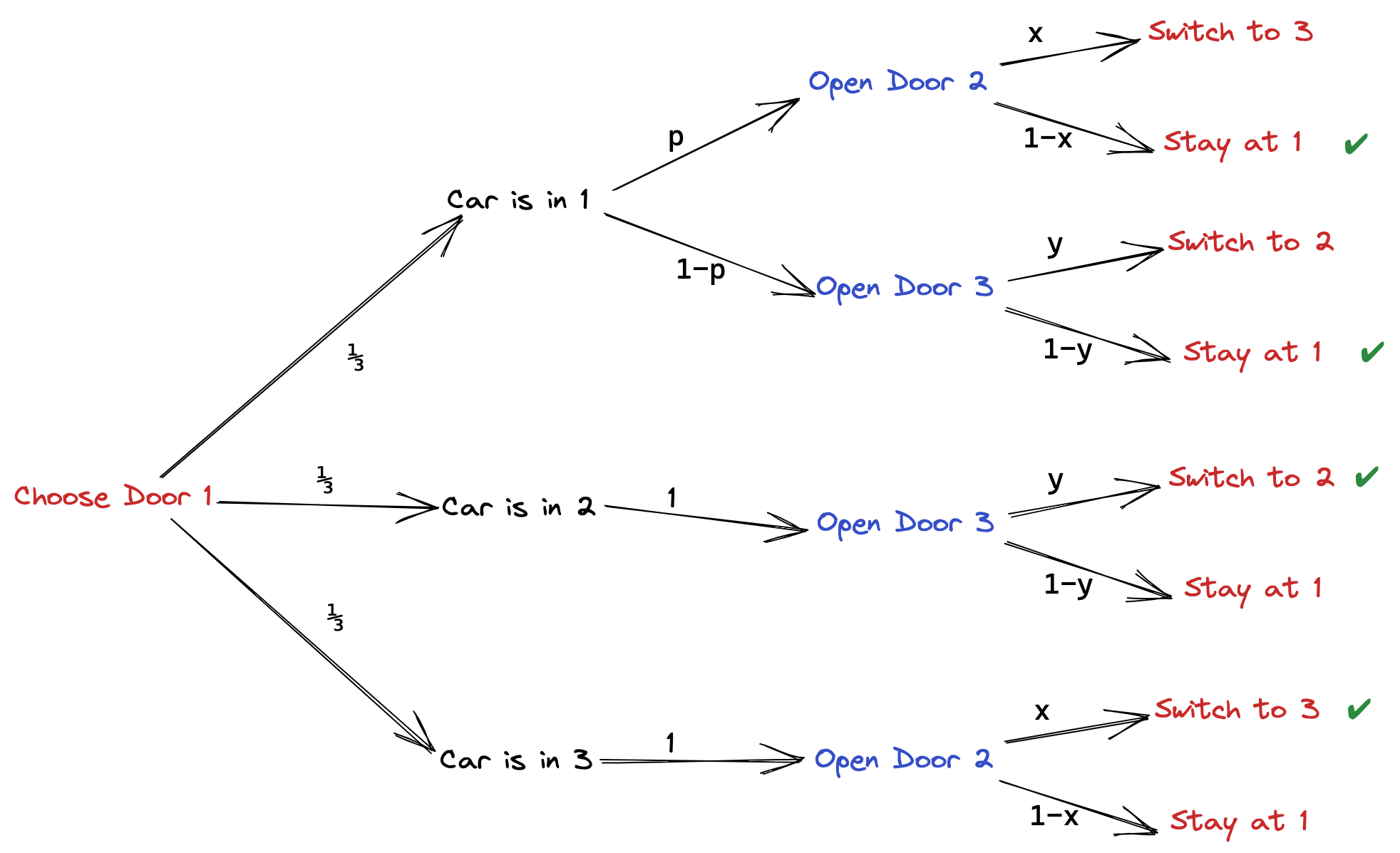

The parameterization argument, drawing a decision tree

Assume without loss of generality that you always start by picking door #1. Now, the only freedom Monty has is to choose which door to open. He can only exercise this freedom when you have in fact chosen the car. In this case, let p be the probability that Monty chooses to open door #2, and let (1-p) be the probability that Monty chooses to open door #3. This parameter completely encodes Monty’s part of the strategy.

Now, what about your part of the strategy? Well, all that you can choose is:

- Your probability of switching if Monty opens door #2. (Call this x)

- Your probability of switching if Monty opens door #3. (Call this y)

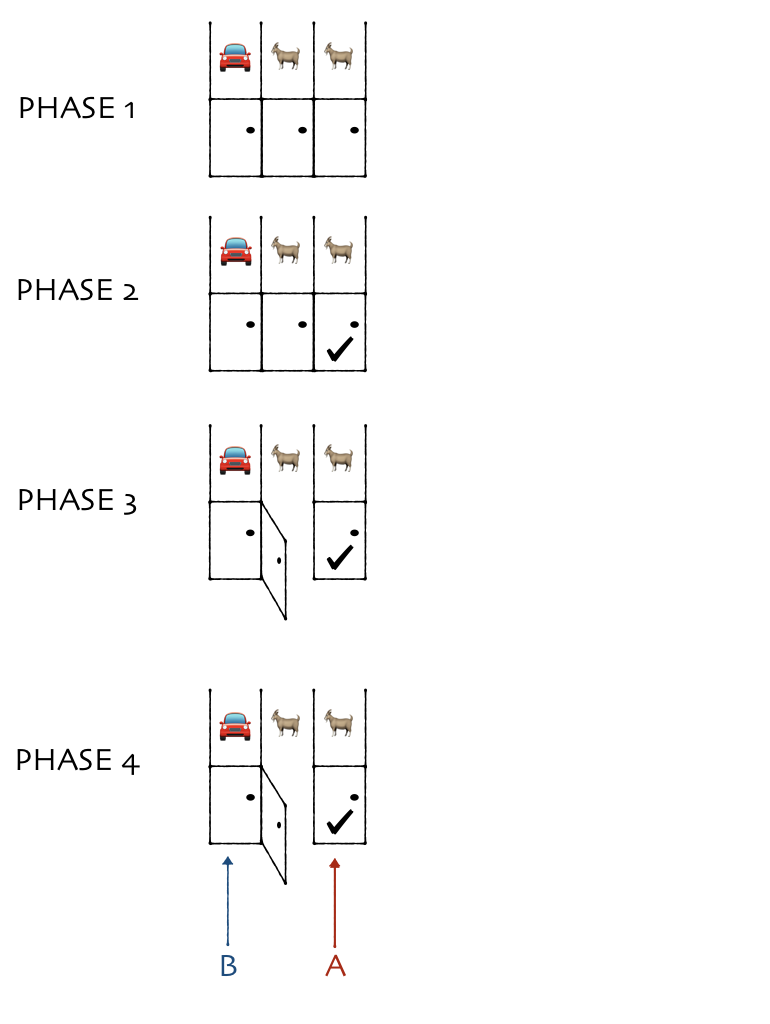

Now, draw a graph of all the possible outcomes

If you add up all the winning paths, you get:

ℙ[win]

= ⅓ ( p (1-x) + (1-p) (1-y) + y + x )

= ⅓ (1 + (1- p) x + p y )

Since p and (1-p) are non-negative numbers, an optimal strategy is to use x=y=1, for which the win probability becomes ℙ[win]=⅔.

Credit: Marte (who also drew the above beautiful graph)

Why you might not like this argument: If you made it this far, I think that’s impossible.