Have a consistent ruleset. Titles are a black art. Have empathy for the brain’s parser. It’s impossible to follow all the conventions. Write a thesis statement even if you hate it

Stephen King (On Writing, 2000)

Here’s how Stephen King writes a novel:

- He has a vague story idea.

- He creates some characters.

- He places those characters in a situation.

- He writes the novel from beginning to end.

Here’s how he writes well: He lets the characters do what they want. He warns against plot. If a rigid set of events must happen, characters become unreal and robotic. Let them breathe and accept things might stray from your original vision.

There’s an analogy to science fiction, where the cardinal sin is unclear rulesets. Good science fiction states the rules of the game and then follows them. It’s OK to have faster-than-light travel or telepathic aliens, but explain what’s possible and stick with it. There are no stakes if the characters are always rescued by their robot butler revealing some previously unknown superpower.

Both King’s formula and good science fiction are based on the same principle: Set up a system with a ruleset and then let it go. The fun is in watching how things evolve from the initial conditions.

Stein Sol (Stein on Writing, 1995)

Sol liked to spy on people at bookstores. He gives a brutal picture:

- For 99% of books, they scan the title and move on.

- If they pick up a book, they usually just skim the cover or first page.

- No one gets past the third page before either buying it or putting it back.

He stresses: Unless you’re famous, the title and introduction are what determine if anyone reads you.

For introductions he says to give a surprising personality or action so the reader will hunger for more. Here are some great first sentences.

- “You must not tell anyone”, my mother said, “what I am about to tell you.”

- At exactly 10:19 A.M. yesterday, a grandmother’s purse on a conveyor belt at Orange County airport set off an alarm that caused two security guards to rush to the scene.

- I have long been an admirer of the octopus.

For titles, he gives examples of what the author wanted versus what was published.

- Diego Rivera → The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera

- The Battle of Schmidt → Follow Me and Die

- The Anatolian Smile → America America

- The Eye and the Ear → A Moveable Feast

- Twilight → The Sound and the Fury

There’s no formula. The takeaway is that these choices are important, some people are good at making them, Stein Sol is one of those people, and all the authors who refused to listen to him did so at their peril.

Steven Pinker (The Sense of Style, 2014)

The view that beating a third-rate Serbian military that for the third time in a decade is brutally targeting civilians is hardly worth the effort is not based on a lack of understanding of what is occurring on the ground.

It’s not a lack of understanding of what is occurring on the ground that creates the view that it’s hardly worth the effort to beat a third-rate Serbian military that is brutally targeting civilians for the third time in a decade.

The first quote above is a monstrosity, the second merely bad. Why?

You may suspect a simple trick. But look at the transformation. We’ve permuted chunks ABCDE into EDABC.

The view that beating a third-rate Serbian military that for the third time in a decade is brutally targeting civilians is hardly worth the effort is not based on a lack of understanding of what is occurring on the ground.

It’s not a lack of understanding of what is occurring on the ground that creates the view that it’s hardly worth the effort to beat a third-rate Serbian military that is brutally targeting civilians for the third time in a decade.

According to Pinker, the second is better because of the algorithm your brain uses to parse English text. I guess that’s a tautology, but it’s helpful once you get specific about the heuristics our brains use.

Principle 1: Avoid left-branching.

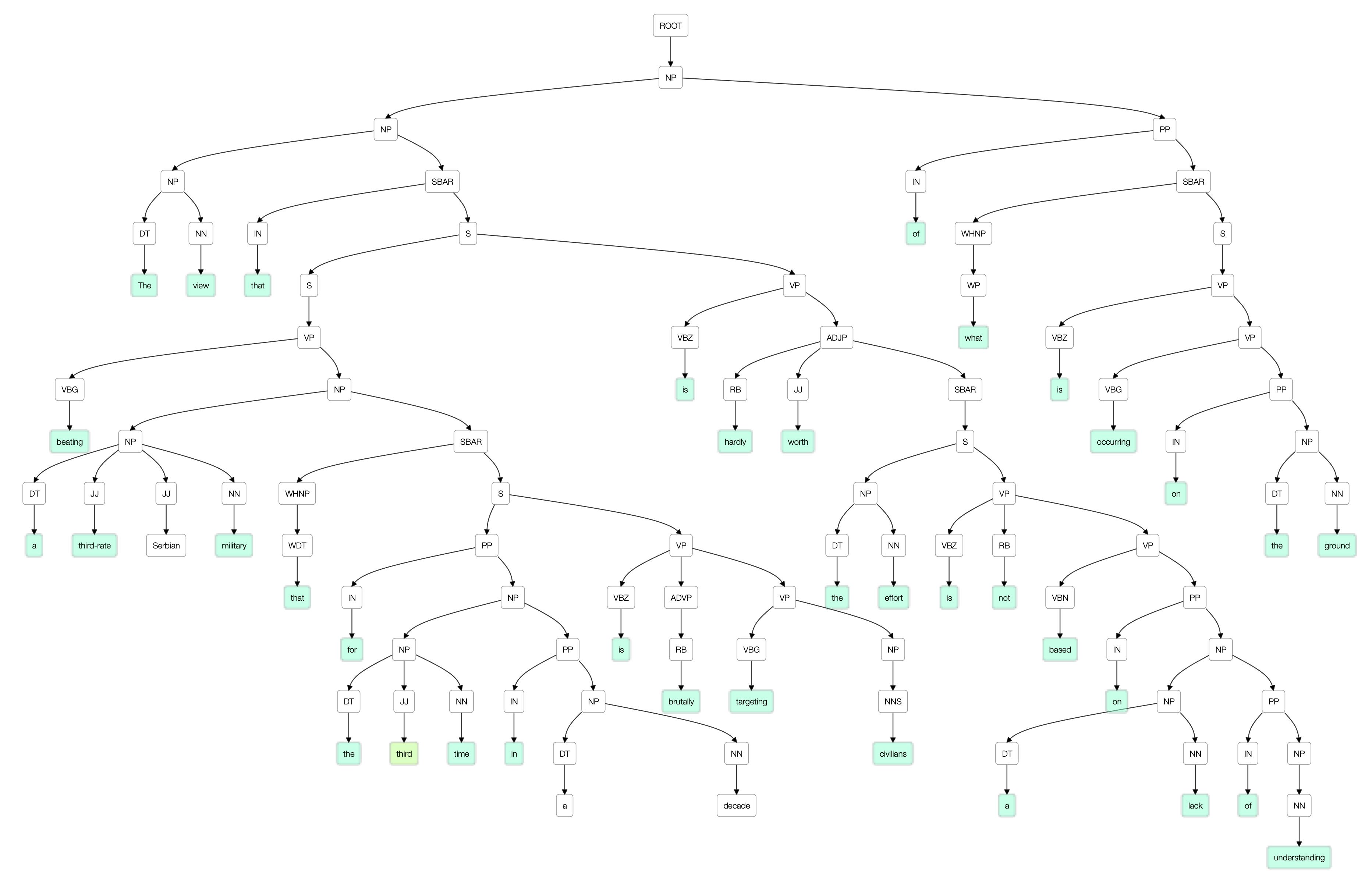

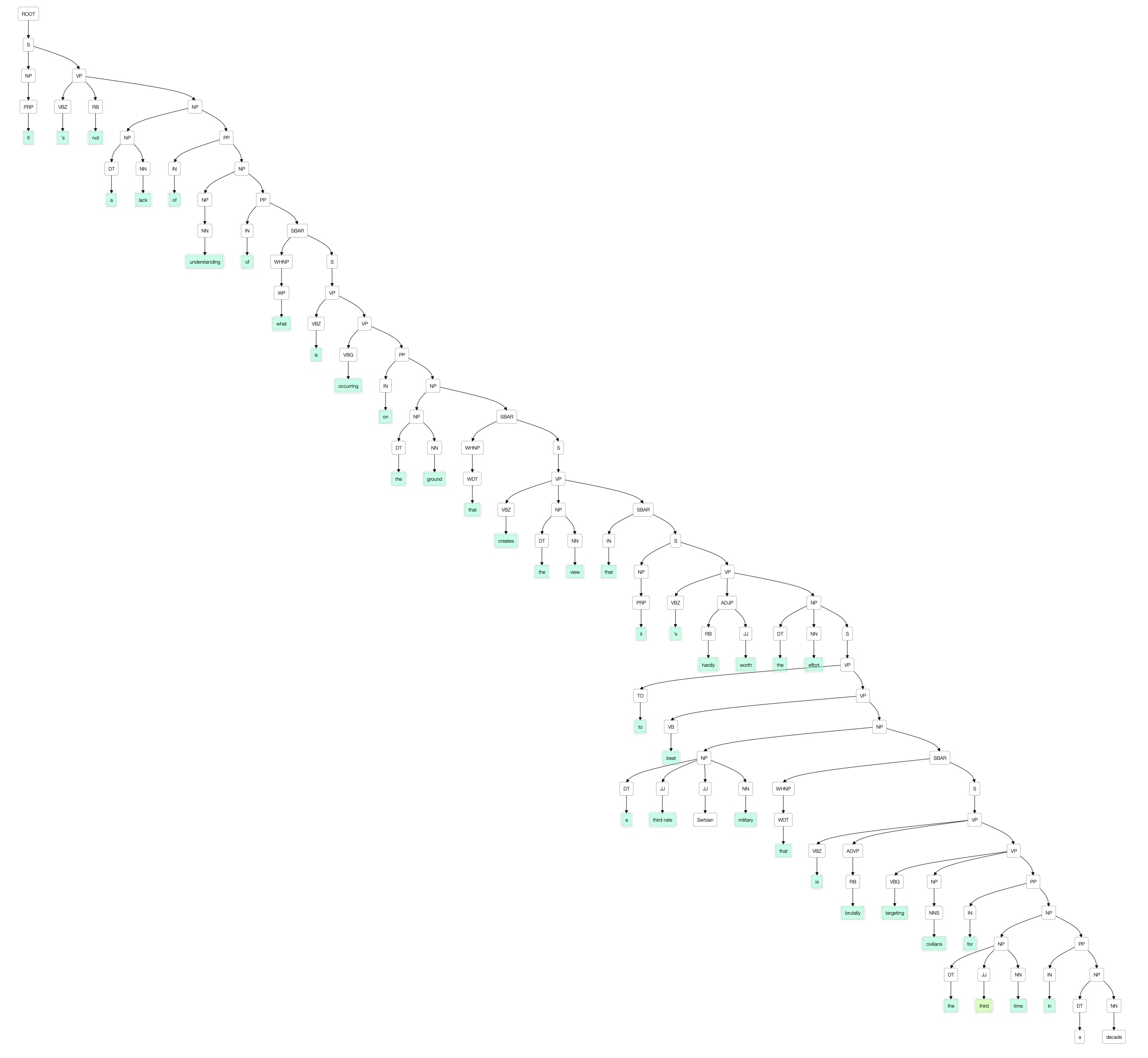

We can understand the difference between the two sentences if we draw syntax trees. Here’s the first sentence:

As you can see, there’s a rather deep tree with branching on both sides.

Meanwhile, the second sentence forms an extremely imbalanced tree. This is good, provided it all goes to the right.

The first sentence has lots of left-branching. This is harder to parse since there’s less context. Picture your brain partway through the first sentence. It will be deep in left part of the first tree above, with no idea what’s on all the right branches. While parsing the second sentence, you never have more than a few “open branches”.

Say you’ve got a long sentence, and you wonder if it’s hard to read. How would you use this insight? This suggests the following procedure.

- Draw a parse tree for it.

- Are there long left-branches in the tree? If so, it’s probably hard to read. You should rewrite to eliminate them.

- Are there long right-branches? Then it might be OK.

This is a much more nuanced way of looking at things than the typical advice that sentences shouldn’t be longer than 25 words or whatever.

Principle 2: Avoid Garden Paths.

Even worse than left-branching is multiple valid parses.

I enthusiastically recommend this candidate with no qualifications whatsoever.

(Who lacks qualifications, the candidate or the recommendation?)

Ambiguous sentences are relatively rare. Given their humorous value, they are probably a net-positive for humanity. More common and problematic are garden paths. These have local ambiguities so the reader starts to build one tree, then has to backtrack when later information arrives.

The man who hunts ducks out on weekends.

This sentence only has one parse, yet it’s confusing because your brain knows that “hunts ducks” usually bind together. Near the end of the sentence you expect something like “…on the lake.” When you see “…on weekends”, you need to start over.

The man who hunts goes out on weekends.

This is easy to understand because “hunts goes” doesn’t mean anything.

Garden paths are easy to write, yet are rare in spoken language. Speakers naturally use tone and rhythm to clarify meaning. Be careful not to imagine these clues when writing, since readers only get bare words.

While classic style guides call to omit needless words, this is not always good advice. Sometimes extra words can improve clarity by making it more obvious what a word means. Compare these:

Light cranes lead us right to bass.

Light-colored cranes then lead us to the right, to some bass.

If the first sentence is read in context, a reader might be able to figure out what which meaning of light, crane, lead, right, and bass are intended. But why make them do that? Sometimes longer text is faster to read.

Principle 3: Context first

What is it that’s so annoying about this sentence?

Noise pollution is one the downsides of using a box fans mentioned in the DIY air purifier post on this site.

It’s hard to read because it starts straight-away with the details, and only gives you context later. If we put the old information first, it becomes much easier to read.

This site’s post of DIY air purifiers using a box fans mentions that one downside is noise pollution.

When style guides tell you not to use the passive voice, this is why. The passive voice usually puts the wrong information at the wrong part of the sentence. But not always. Here’s an example of a sentence written with the active voice:

Several people with theories about laminar airflow and pressure gradients commented on my article about DIY air purifiers.

If we swap in the passive voice, there’s a clear improvement:

My article about DIY air purifiers was commented on by several people with theories about laminar airflow and pressure gradients.

I am old news. Pressure gradients are new. They belong at the end, and the passive voice is a perfectly legit way of putting them there.

For related issues, I recommend The Science of Scientific Writing, a wonderful article from 1990 by Gopen and Swan.

Benjamin Dreyer (Dreyer’s English, 2019)

This explains punctuation, commonly misspelled words, when to write out a number, how long dashes should be, and how to (not) borrow words from other languages. He disparages some common advice, such as to avoid sentence fragments or that you can’t start a sentence with but. On the other hand, he insists on other rules such as that terminal periods “are always set inside.” It’s hard to tell the difference between the arbitrary illogical rules that we should happily ignore and the arbitrary illogical rules that only a simpleton would ever break.

All the same, I’d like to do as he says, but there are a lot of rules. My unavoidable takeaway is that I’ll never remember or obey half of them. Unless you’re an aspiring editor, I’m not sure I’d recommend this book. The fact that I still enjoyed all three hundred pages is a testament to Dreyer’s outlandishly compelling style.

Matthew Yglesias

This was just a tweet, not a book.

THE professional journalist habit that could easily improve 90% of writing by smart, knowledgeable amateurs is making sure to check that you’ve written a strong lede with a clear thesis statement.

This might be bad advice for the New Yorker. Still, if you’re unsure if it applies to you, it probably does. It’s easy to fantasize about readers savoring each subtle turn of your masterpiece. In reality, it’s very hard to make even your highest-level message clear.

Bonus: Larry McEnerney

This isn’t even a piece of writing. It’s a lecture. Still, it changed how I look at writing, and to some degree life. He asks the audience what makes good non-fiction writing. They give answers like:

- Persuasive

- Organized

- Clear

Sure, he says, these are kind of interesting, but the real answer is:

- Valuable

The only thing that matters is if the reader gets something they want. Why have a thesis statement? Because life is short, and people shouldn’t waste time reading something they don’t care about. Do arcane style guidelines matter? Only if it matters to your readers. Is beauty or clarity more important? It depends on if people are reading for aesthetics or information.

He also stresses to avoid perfectionism. Very, very little non-fiction from 100 years is still read today. Writing is less ephemeral than talking, but it’s still a conversation. It will be forgotten. It won’t make you immortal— nothing will. Once you’ve said what you want to say, move on.