It turns out that sales tax has a huge, gigantic, terrible flaw: It punishes specialized businesses. A value added tax (VAT) has no such problems.

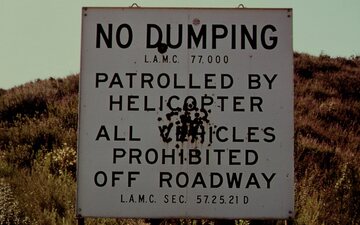

The US has sales tax. Most of the planet has VAT.

Maybe it’s not the most important issue in the world, but it’s just so clear. Sales tax is dumb and VAT is better.

Before We Begin

Many people apparently believe that in the US today, sales tax is only paid by final consumers. THIS IS FALSE. It varies hugely by state, but the current situation is a hybrid between a “pure final retail consumer only” sales tax and what the toy model below describes. You can debate if it’s “sales tax” or “gross receipts tax” or whatever, but it’s a fact that businesses pay tax on business inputs all the time. You can find proof of this here or here or here or here.

I emphasize that the explanation below is a toy, intended to illustrate in the simplest possible way how specialization gets punished when transfers are taxed in proportion to their values. The current reality not nearly this bad due to many complex exemptions, as I discuss at the end. But the flaw described does exist and does punish specialization.

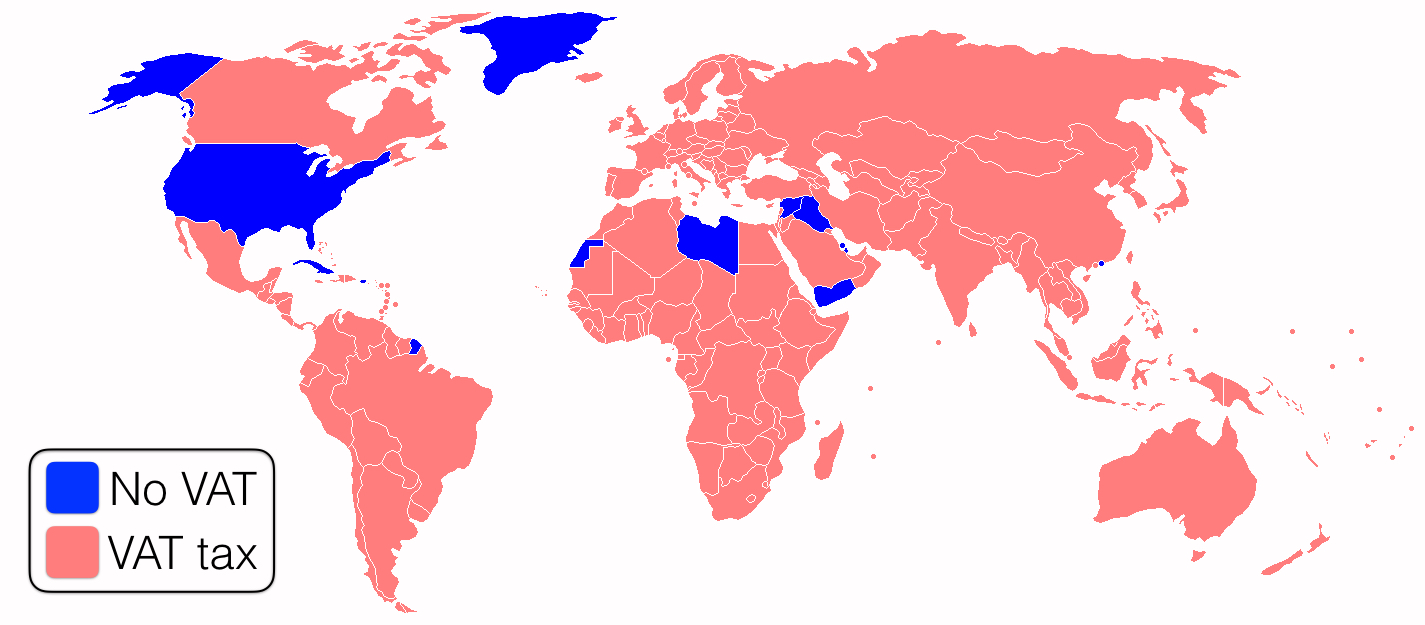

The Decorative Coconut Model

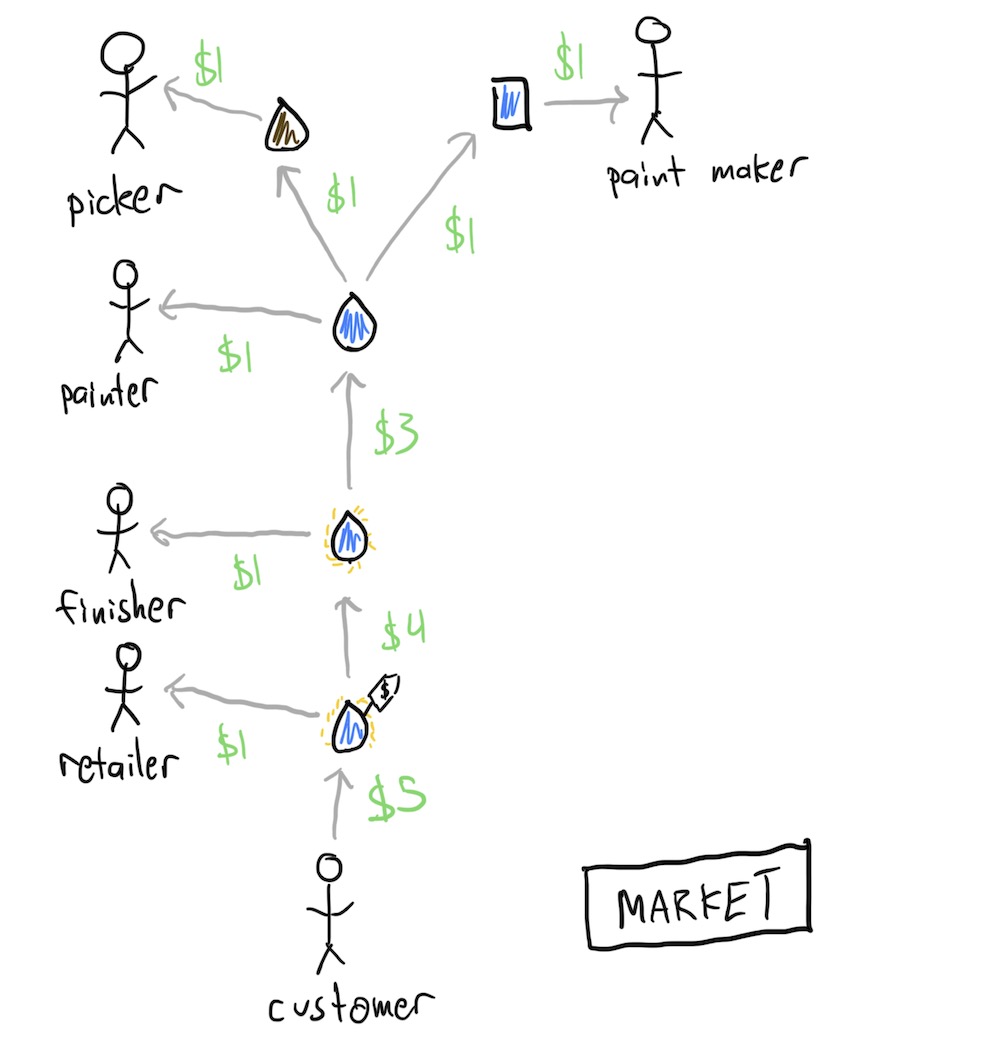

Say you decide to get into the decorative coconut manufacturing business.

You’re good at painting coconuts. You find a friend who is good at picking them, and another who’s good at making coconut paint. You find a third friend who’s a genius with applying finishing lacquer and a fourth who runs a store.

You buy coconuts and paint, apply the paint, then sell to the finisher. He applies lacquer and sells to a retailer.

After negotiating prices, you settle on $1 for a raw coconut, $1 for a coconut’s worth of paint, $3 for a painted coconut, $4 for a finished coconut, and $5 retail. This works out to everyone making $1 of profit.

Here’s a table showing the accounts:

| Item | Cost of inputs | Profit | Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw coconuts | $0 | $1 | $1 |

| Paint | $0 | $1 | $1 |

| Painted coconut | $2 (raw coconut+paint) | $1 | $3 |

| Finished coconut | $3 (painted coconut) | $1 | $4 |

| Retail coconut | $4 (finished coconut) | $1 | $5 |

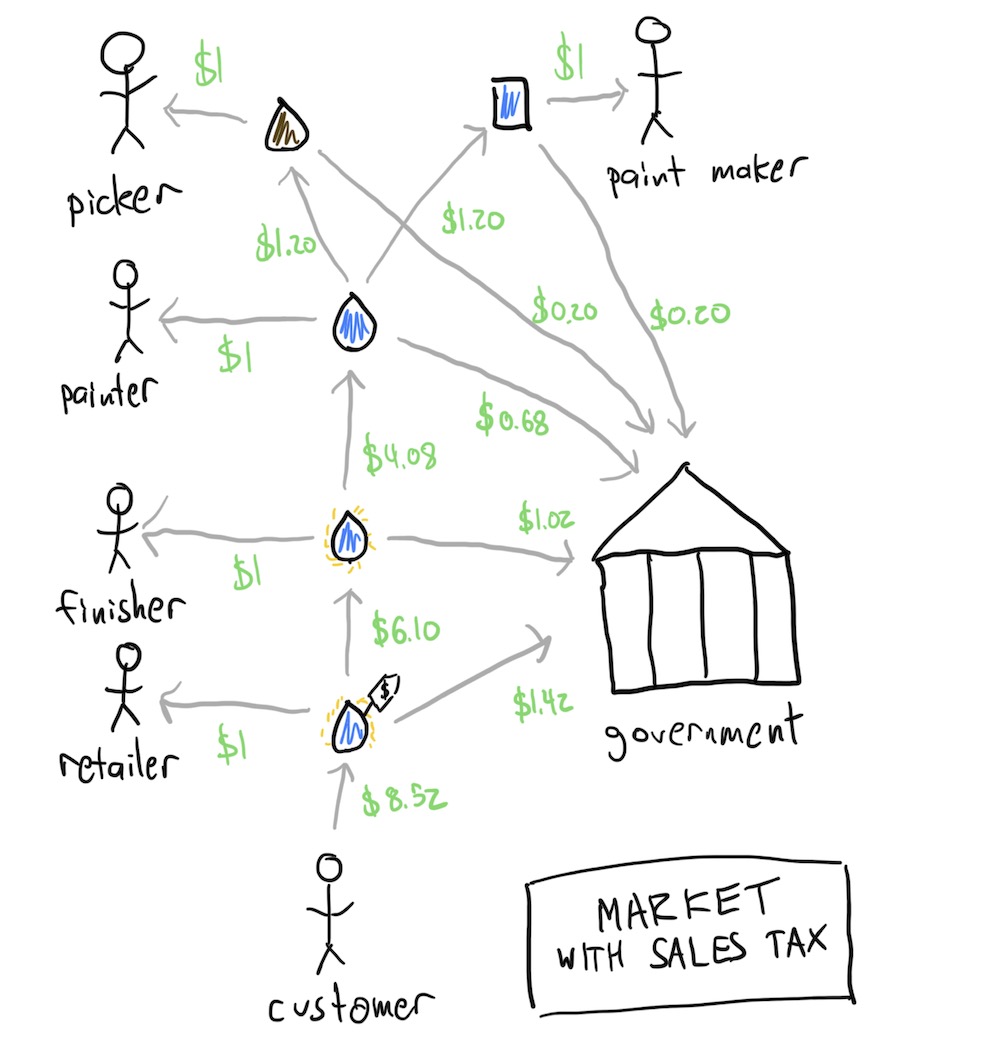

The Sales Tax Regime

For a while, everything runs beautifully. Every day you wake eager to help capture more beauty in coconut form — and then the government announces a 20% sales tax. Whenever you sell something, you need to pay 20% of the sale price to the government.

You talk it over. Everyone feels they still deserve to make the same $1 profit as before. Since you now pay $1.20 for a raw coconut and $1.20 for paint, you need to mark up to $3.40 before tax, and $4.08 after.

After everyone marks up their prices in this way, here are the results:

| Item | Cost of inputs | Profit | Price | Price after tax |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw coconut | $0 | $1 | $1 | $1.2 |

| Paint | $0 | $1 | $1 | $1.2 |

| Painted coconut | $2.4 | $1 | $3.40 | $4.08 |

| Finished coconut | $4.08 | $1 | $5.08 | $6.10 |

| Retail coconut | $6.10 | $1 | $7.10 | $8.52 |

Your customers aren’t thrilled about the increase in price, but what are they going to do — live without painted coconuts? So they pay the higher price, the government gets its tax, and life continues.

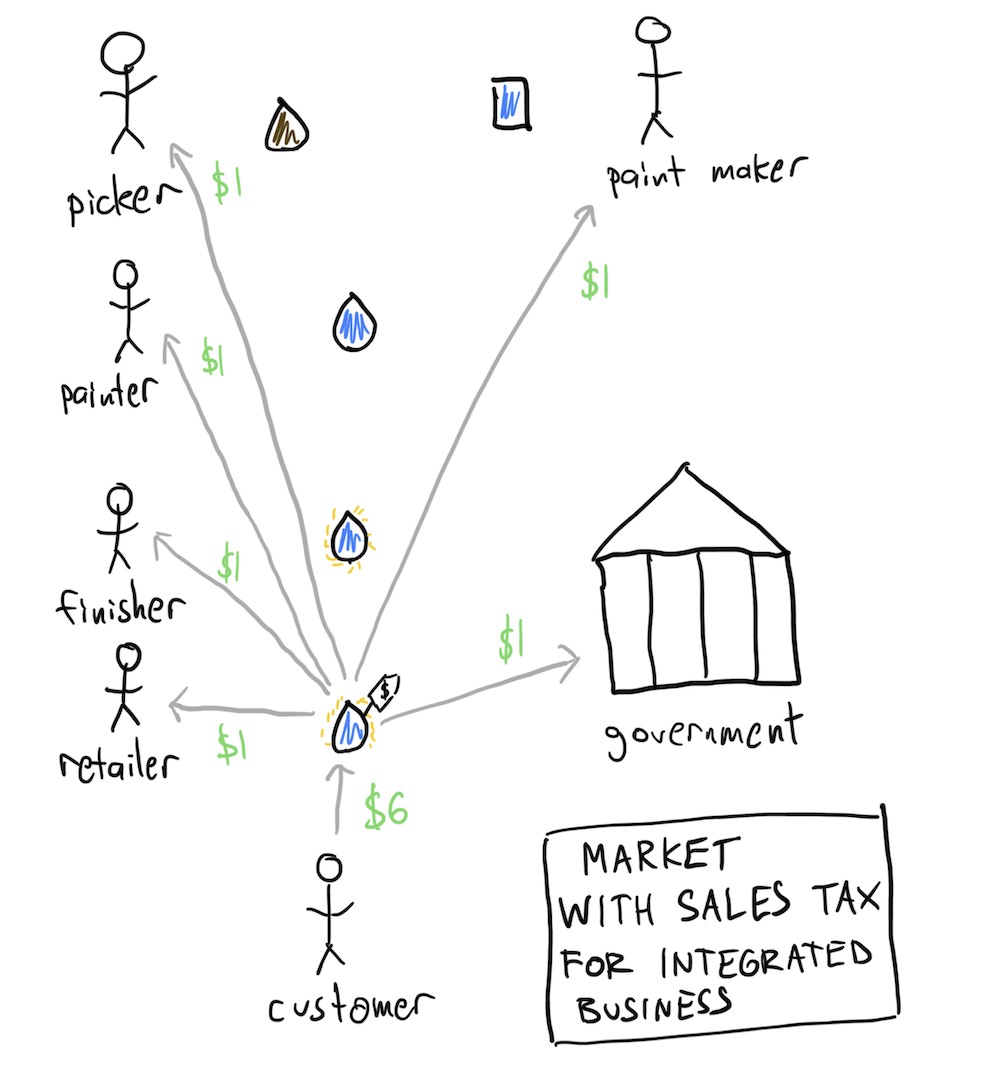

Your Annoying Cousin

A few months later, your unscrupulous cousin hears about your business. He’s the jealous type and decides to try stealing your customers. He opens a store and finds four friends to help make coconuts. Unlike you, however, he hires everyone as employees. He sells the coconuts for $6 ($5 plus tax) and gives everyone $1 per coconut in wages.

Your cousin and friends don’t appreciate the subtle art of coconut decoration. Everyone agrees yours are better but they start to complain: Why are you charging $8.52 when a slightly worse product is available for only $6? Slowly, your loyal customers drift away and you go out of business.

How could this happen? Your team was asking for the same profit while doing a better job! Yet everyone is left with your cousin’s knock-off coconuts.

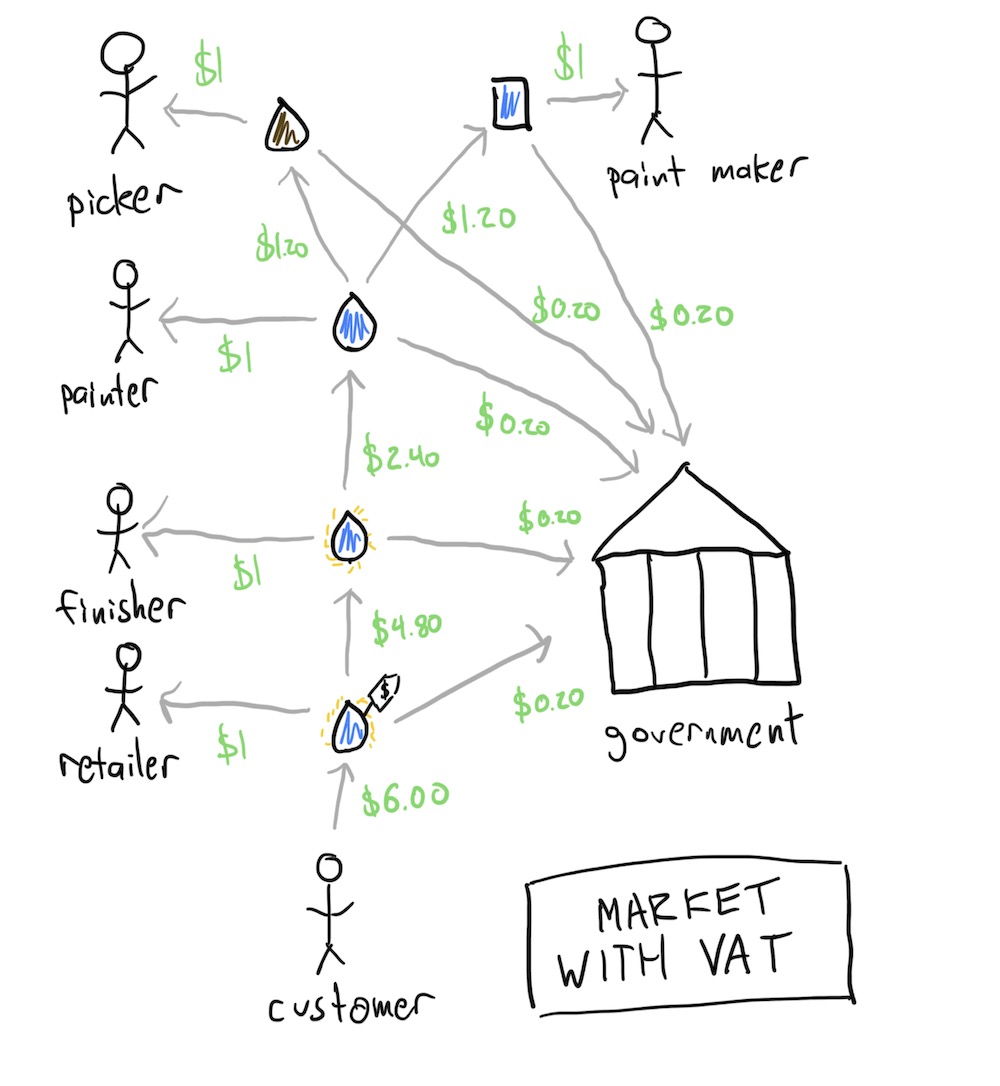

The VAT Regime

Suppose the government had instead announced a 20% VAT. With a VAT, whenever you sell something, you only pay tax on the sale price minus the price of the stuff you bought to make it.

As before, you’ll need to pay $1.20 for raw coconuts and $1.20 paint. You charge $3.40 for painted coconuts, now you’re only taxed on the profit of $3.40-$2.40=$1.00. The price with tax is now $3.60.

Here are the final prices as they go through through the system. Everyone is making a profit of $1, so everyone pays a tax of $0.20.

| Item | Cost of inputs | Profit | Price | Price after tax |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw coconut | $0 | $1 | $1 | $1.2 |

| Paint | $0 | $1 | $1 | $1.2 |

| Painted coconut | $2.4 | $1 | $3.40 | $3.60 |

| Finished coconut | $3.60 | $1 | $4.60 | $4.80 |

| Retail coconut | $4.80 | $1 | $5.80 | $6.00 |

The final price is $6.00. Since your coconuts are better, your cousin won’t be able to drive you out of business with his low-grade stuff.

The Problem with Sales Tax

What happened? Your cousin created a vertically integrated business. A sales tax is collected every time someone buys something. If you just do it yourself, no tax is collected.

Are vertically integrated businesses bad? Not necessarily.

However, take your chain of independent independent artisans making and selling coconut products. Imagine someone invents a paint that customers prefer. You almost have to switch, or some other painter will drive you out of business. Contrast this with cousin’s integrated business making all coconuts. In theory, the inventor could convince your cousin to hire him or license the paint process. If he won’t be convinced, the only way for that paint to get to customers is if the inventor develops an entire independent coconut manufacturing chain. Vertical integration means there are price signals at fewer points during production, which tends to make it harder for innovations to thrive.

There are times where vertical integration is better. (If everyone is independent, a lot of time is spent on negotiations!) That’s perfectly fine. What we don’t want is to artificially encourage vertical integration even when it’s less efficient, which sales tax does.

The VAT Advantage

Another advantage of the VAT is it tends to be easier to enforce. When I sell something, I need to provide certificates proving I paid VAT on my inputs. This gives everyone an incentive to ensure compliance in the previous layer of the chain. With a sales tax, the government needs to watch every single transaction.

Of course, people know sales tax is distortionary. Many exceptions exist to minimize the worst distortions. For example, a retailer usually won’t pay sales tax on a manufactured good they intend to a consumer in the same form. Without this exception, we’d probably have a crazy economy where manufacterers sell directly to consumers. The messy patchwork of exceptions reduces the problems with sales tax but doesn’t eliminate them.

I think there are two major reasons to oppose replacing sales tax with VAT. The first is a Leninist “worse is better” attitude. If you think all taxes are bad then you’d want to keep them painful and visible so people will be maximally annoyed by them. The second is that VAT is complicated to administer, particularly when sales tax can be different in each local area. This might be true, but I find it a bit hard to believe. VAT is more self-enforcing and sales taxes are already a nightmare, particularly for anyone selling to different cities/states. If we’re keeping the sales tax to keep things simple, where’s the payoff?

Notes

- The initial map is based on Wikipedia, but found that many places (Thailand, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Oman, UAE, Kuwait, Angola, Liberia) have recently implemented VAT. I checked that most of the others (Jordan, Greenland, French Guinana, Cuba, Libya, Hong Hong) still do not have a VAT.

- To be sure, if you could implement a sales tax that only applied to final consumers, that would be economically equivalent to VAT. Is that how state taxes work in the US? It’s hard to make simple generalizations because (1) it’s sometimes hard to say what a “final consumer” is (2) there are different laws in each state and (3) the relevant tax is sometimes called a “gross receipts” tax. The important question is: Does the US have taxes on intermediate products that “cascade” like described in the above model? The answer to that question is YES.