Here’s an Obvious Problem:

- There are 10 doors. A car is behind a random door, goats behind the others.

- Do you want what’s behind door 1, or what’s behind all the other doors?

That’s easy, right? Well, how about the Monty Hall problem?

- There are three doors. A car is behind one random door, goats behind the others.

- You pick one door.

- The host picks another door that contains a goat and opens it.

- Should you keep your original door, or switch to the other closed door?

Many people guess it doesn’t matter if you switch. But in reality, switching gets you the car 2/3 of the time.

This post claims that these problems are really just disguised versions of each other. We’ll start with the Obvious Problem, apply a series of small changes that clearly don’t change the solution, and end up at the Monty Hall problem.

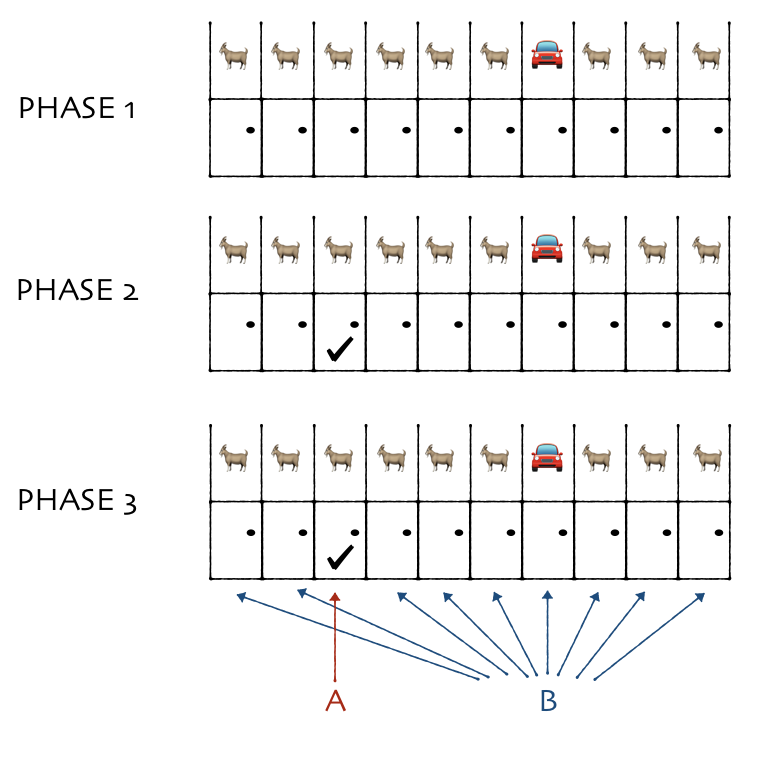

Game 1

Here’s our first game.

- There are 10 doors. A car is randomly placed behind one, and goats behind the other 9.

- You pick one door.

- You get two options:

- Option A: You get whatever is behind the door you picked.

- Option B: You get whatever is behind all of the other 9 doors.

There’s nothing mysterious here. You should choose option B. There’s only a 10% chance you picked the right door, so there’s a 90% chance the car is behind one of the others.

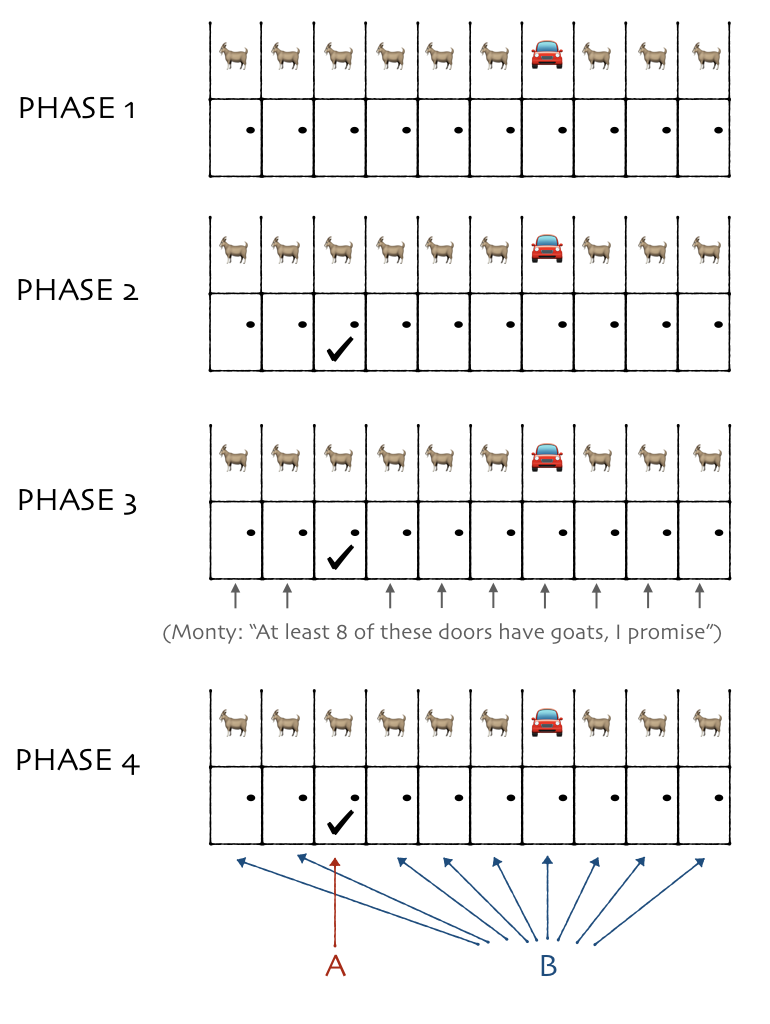

Game 2

Now, we slightly update the game (new part in bold).

- There are 10 doors. A car is randomly placed behind one, and goats behind the other 9.

- You pick one door.

- Monty says “Hey! I promise you that there is a goat behind at least 8 of the other 9 doors!”

- You get two options:

- Option A: You get whatever is behind the door you picked.

- Option B: You get whatever is behind all of the other 9 doors.

Monty’s statement changes nothing. You don’t need to rely on his trustworthy looks. You already knew there were at least 8 goats! Option B still gets you the car 90% of the time.

Game 3

Let’s update the game again (new part in bold).

- There are 10 doors. A car is randomly placed behind one, and goats behind the other 9.

- You pick one door.

- Monty looks behind the other 9 doors. He chooses 8 with goats behind them, and opens them.

- You get two options:

- Option A: You get whatever is behind the door you picked.

- Option B: You get whatever is behind all of the other 9 doors.

The key insight is this: When Monty shows you that 8 of the 9 other doors contain goats, you haven’t learned anything relevant to your decision. You already knew there were at least 8 goats behind the other doors! So this is just like game 2. Option B still gets you the car 90% of the time.

Want more intuition? Suppose you picked door 3. Imagine Monty walking past the doors, opening doors 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, skipping 7, then opening 8, 9, and 10. Doesn’t door 7 seem special?

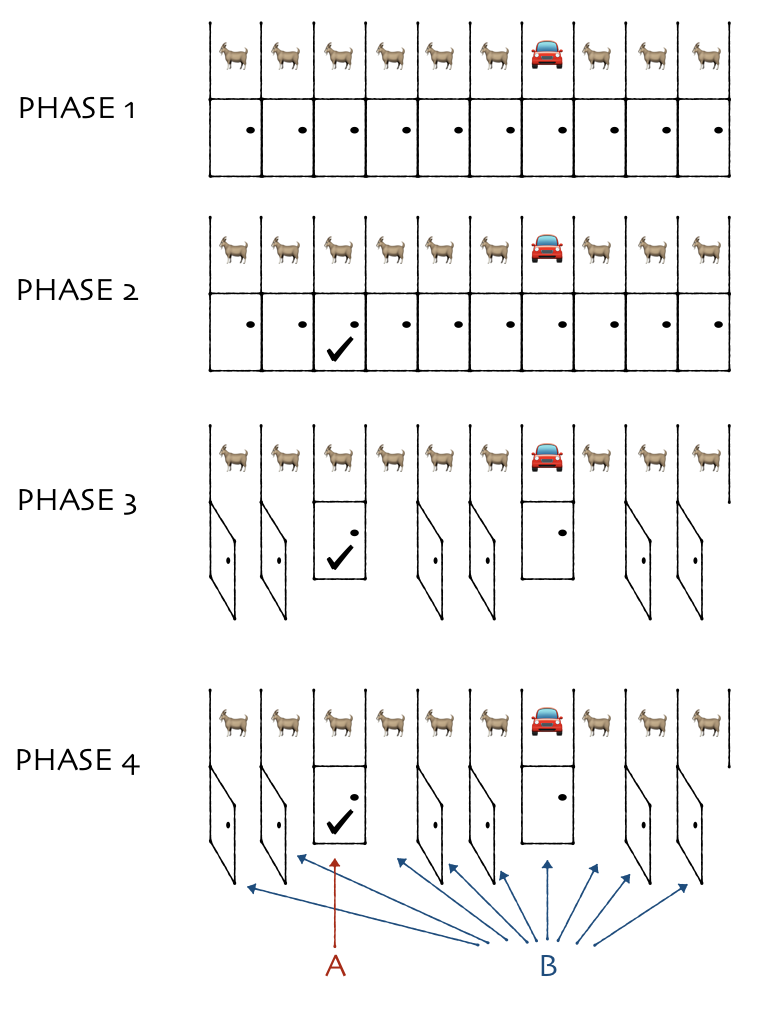

Game 4

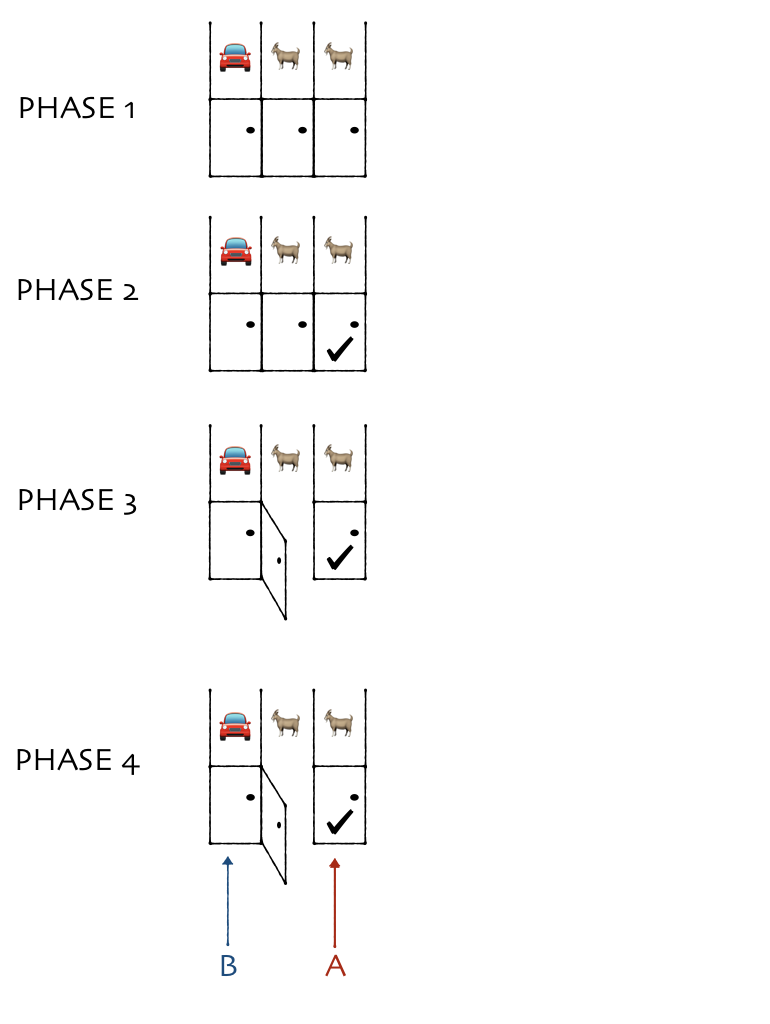

Let’s make another change. Finally, we arrive at a game very similar to Monty Hall.

- There are 10 doors. A car is randomly placed behind one, and goats behind the other 9.

- You pick one door.

- Monty looks behind the other 9 doors. He chooses 8 of them with goats behind them, and opens them.

- You get two options:

- Option A: You get whatever is behind the door you picked.

- Option B: You get whatever is behind the other closed door.

The only difference with Game 3 is that option B doesn’t get you the 8 visible goats. Since you don’t care about goats, this makes no difference. This is still just like game 3. You get the car 90% of the time by switching.

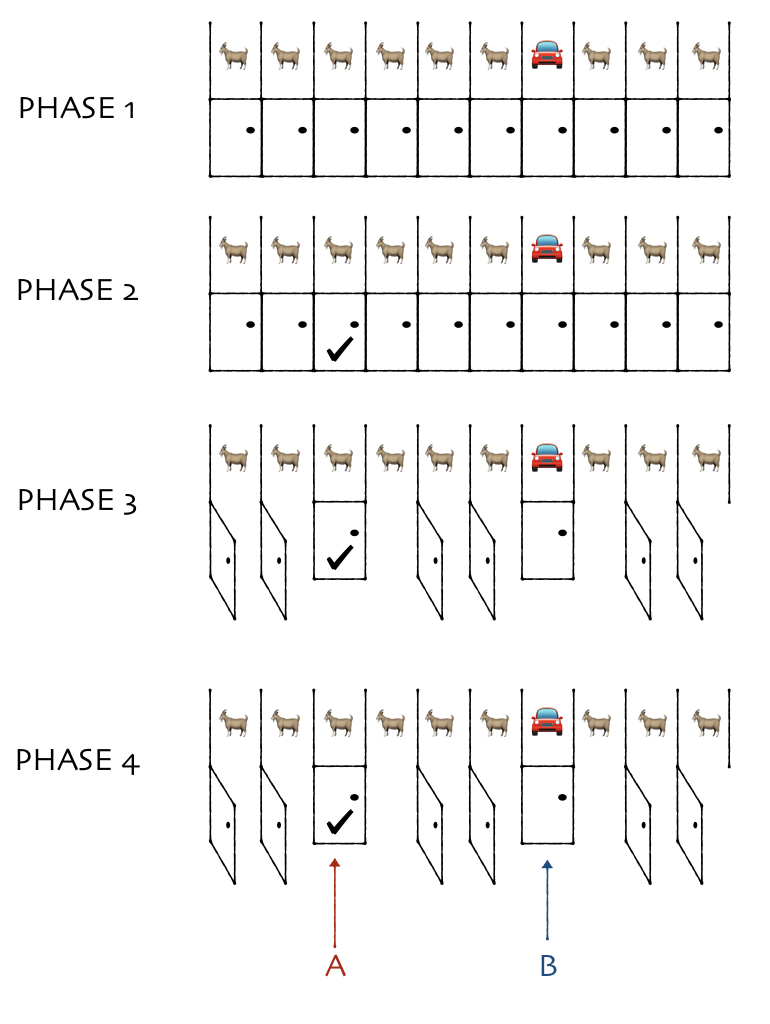

Game 5 (Classic Monty Hall)

Here is the last game. We just change the number of doors from 10 to 3.

- There are 3 doors. A car is randomly placed behind one, and goats behind the other 2.

- You pick one door.

- Monty looks behind the other 2 doors. He chooses one 1 of them with a goat behind it, and opens it.

- You get two options:

- Option A: You get whatever is behind the door you picked.

- Option B: You get whatever is behind the other closed door.

Of course, you still want to choose option B. The chance of success is now 2/3 instead of 9/10. This game is exactly Monty Hall, so we’re done.

Side Notes

-

The “best” way to think about the Monty Hall problem is simple: There’s a 2/3 chance at the beginning that you picked a door with a goat behind it, and nothing that happens after changes that. The only purpose of the extra steps above is to give more intuition for why the extra information you get from opening a door doesn’t change the probabilities.

-

It’s important that Monty looked behind the doors before choosing which to open. This is where people’s intuition usually fails. If he had chosen a door at random — in a way that he risked possibly exposing a car, then the situation would be different. (In that case, there’s no advantage or harm in switching.) But he doesn’t choose the door at random. He deliberately chooses to show you goats. Since this is always possible, it tells you nothing. I think this is the crux of what makes this problem unintuitive: If the host had picked a random door, the intuition that it doesn’t matter if you switch would be correct!

- It might be helpful to draw a diagram of the relationship of the different games, starting with classic Monty Hall and ending with the Obvious version.

Game 5 (Classic Monty Hall)

↓

Use 10 doors instead of 3.

↓

Game 4

↓

If you switch, you get the contents of all other doors, not just the other closed door.

↓

Game 3

↓

Monty promises 8 goats behind the other doors instead of showing you.

↓

Game 2

↓

Monty doesn’t bother promising.

↓

Game 1 (Obvious Monty Hall)

-

There are some other attempts at variants of the Monty Hall problem, also intended to be more intuitive. These involve switching the doors for “boxers”.

-

Monty Hall was named “Monte” at birth! Given that Monte Carlo simulations are often used for exploring the Monty Hall problem, that’s either a miracle for confused students or a tragedy for puns.