You want to go to Mars. There’s a machine that will scan and destroy all the matter in your body, send the locations of every atom to Mars, and then recreate it. You worry: Does this transport you, or does it kill you and make a new copy?

Still, your friends use the machine and they seem fine. And you figure you’re a pattern of atoms, not the atoms themselves, so you decide to take the machine. After you press the button to start it, you’re surprised to find that you’re still on Earth. You ask the technician, “Did the machine fail?”

“No, no”, he responds, “Did we not tell you? The new scanner records your blueprint without destroying your body. Not to worry, we’ve already transmitted the information to Mars. This body will be destroyed in a few minutes.”

You see that the final effect is the same. But still, are you upset about this?

You’ve probably heard some version of this thought experiment before. It originally comes from Derek Parfit’s 1984 book Reasons and Persons. He claims to answer if you’re being transported or killed, and then reflects on how to think about your future self, abortion, the morality of prisons, and your own mortality.

Spectrum arguments

Let’s start with three arguments all reminiscent of the ship of Theseus or the sorties paradox.

Napoleon’s surgery

You’re going to have a painful surgery, for which you must be awake. But before the surgery, a doctor will use a machine to make your neurons fire so that your personality and memories are completely replaced with those of Napoleon. Does this mean it will be Napoleon who suffers during the surgery, rather than you?

Or, suppose there is a dial: At one end it does nothing, while at the other end it replaces all your memories with Napoleon’s. At what intermediate position do you stop being you?

The death machine

Scientists are going to subject you to another machine with a dial: At one end, nothing happens. At the other end, 100% of your cells will be destroyed and replaced with exact duplicates. Before the machine starts, you wonder, “Am I about to die?” Would that be true if 1% of your cells were replaced? What about 30% or 90%?

The Garbo maker

There’s another machine with a dial. At one end, nothing happens. At the other end, 100% of your cells will be destroyed and replaced with those of Greta Garbo. At intermediate positions, the resulting body, memories, and personality will be a mixture. At what position at which you stop being you and start being Garbo?

No further fact

Parfit answers these questions through an analogy. Say there’s a club that meets for a few years and then stops meeting. A few years later, most of the same people decide to get together at the same place and hold meetings under the same name.

Now: Is that the same club, or a different one?

Parfit calls this question “empty”. This means that without answering the question, we already know everything that has happened. If you do answer the question, that will be you deciding what “same club” means, not you discovering any new facts.

So go back to the teletransportation example. Say you press the button and wake up on Mars. Here are the facts:

-

There was a body on Earth.

-

It was scanned and destroyed and recreated on Mars.

-

The new body has the same memories and experiences the world in the same way.

These are, Parfit argues, all the facts. When you ask if it’s the same person who wakes up on Mars, you are seeking some further fact. But the statements above are a full account of events. There is nothing else to discover.

Why should we believe there is no further fact? This consumes most of 130 dense pages, but it’s basically as follows:

- It’s not clear what this further fact should be.

- If there was a further fact, there could be evidence of it. If we were immortal souls with memories of past lives, a woman in Japan might be able to predict where to dig up jewelry she buried thousands of years ago as a Celt in Europe. But nothing like that ever happens.

- If you assume there is a further fact, then you have to reckon with the questions in the previous scenarios. If self-identity is an all-or-nothing, then there’s some threshold of the dial below which you remain you and above which become Greta Garbo. That would be weird.

- But OK, say you accept that a threshold exists. Then isn’t it odd that there is no possible experiment that would allow us to discover what that threshold is?

Some people ask, aren’t the previous scenarios really just like the ship of Theseus? In a way, yes. But if you replace a ship piece by piece and ask if it’s the same ship, I yawn because it’s obvious that ships are really just big assemblies of wood. But if you replace me piece by piece, you’ll have my full attention, because I start with a much stronger intuition that I am an indivisible thing!

Other arguments

The physics exam

It’s the year 2214. You suffer from severe epilepsy, which has forced doctors to cut the corpus callosum that connects the two hemispheres of your cortex. Unlike those primitives back in the 1960s and 1970s, however, current practice is to replace the corpus callosum with a small computer. It behaves just like your old corpus callosum, except it shuts down during seizures.

One day, you’re preparing for an important exam but no matter how much you study, you can’t do the problems fast enough. So, you come up with a plan: You hack into the computer in your brain and change it to be blink-controlled. As soon as the exam starts, you activate it. This allows you to have each hemisphere of your cortex work on different problems in parallel. You terrify your classmates by writing with both hands at the same time.

Did you become two people? Did one of them die when you re-united your hemispheres after the test?

(Parfit drank the split-brain kool-aid hard. He considered it an indisputable experimental fact that split-brain patients have two separate streams of consciousness and thought—so indisputable that he doesn’t bother to discuss the experiments or why that conclusion follows from them.)

The twins

You’re in an accident. Half your cortex is destroyed. You lose some cognitive function, but you’re still alive. Are you still you?

Or, you and your identical twin are in an accident. Your body is damaged, while your twin’s brain is damaged. If doctors put your brain into your twin’s body, who is the resulting person?

Or, your identical twin is in an accident where their brain is destroyed. You volunteer to have half your brain transplanted into your twin’s body. Both surviving people have your memories and believe themselves to be you. Who one is right?

Branching people

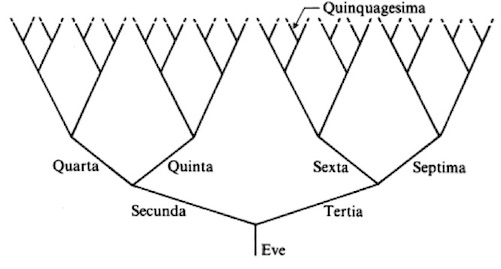

Take a species like humans except they reproduce by asexual division. When someone splits, both of the new copies start with the memories of the parent. These memories fade gradually over the generations.

Now, take Eve and her great-great-great-granddaughter Quinquagesima. When Tertia was born, she was just like Eve, and when Sexta was born, she was just like Tertia. But so many generations have passed that Quinguagesima remembers nothing of Eve or her life.

Are Eve and Quinguagesima the same person? If no, when did Eve die?

Immortals

Take a species like humans except they are immortal. They have memories and experiences like us, but their brain can only hold a finite amount of information, so old memories gradually fade. No one remembers anything from 500 years ago.

If you take a person now, and the same person 500 years from now, are they actually the same person?

Thinking about it

Parfit imagines what various people would think of these arguments.

He reckons Wittgenstein would disapprove: Concepts are based on facts and those concepts don’t make sense anymore in imaginary situations where the facts aren’t true. Still, claiming that personhood is an all-or-nothing thing separate from our brains or bodies also stretches our concepts too far, so we shouldn’t do that either. It’s less that Wittgenstein disagrees and more that even when he’s imaginary it’s still impossible to argue with him.

On the other hand, he thinks the Buddha would agree. Parfit’s argument for this is curious. In the main text just says:

As Appendix J shows, Buddha would have agreed.

But then Appendix J is just a passage from the Visuddhimagga ending with this quote:

The mental and the material are really here,

But here there is no human being to be found.

For it is void and merely fashioned like a doll,

Just suffering piled up like grass and sticks

That’s all rather mysterious, but still: The Buddhist doctrine of anattā is that no unchanging, permanent self or essence can be found in any phenomenon.

Does the self exist?

Parfit is careful never to state that “personal identity does not exist”, but rather that it doesn’t exist in any scenario with “branching”.

I think of this like the identity of physical objects. I can talk about my “favorite toaster” and this is fine. It would be crazy to refuse to use this concept. But if you and I shoot our favorite electrons at each other and ask if they bounced off or passed through each other, quantum physics says that there may not be an answer—it’s not that we don’t know if we’ve traded electrons, the question itself doesn’t make sense.

(Remember, this is just an analogy, I’m not saying consciousness has anything to do with quantum physics, please stop hitting me.)

While Parfit doesn’t explicitly deny that personal identity exists, he does argue that it isn’t important. He also is clear later on that he doesn’t believe in the “separateness” or “non-identity” of different persons. But is not believing in personal identity different from not believing that different people are “non-identical”? If so, I couldn’t figure out how.

Self identity and morality

How should we think about our future selves? If you’re self-interested, then an extreme claim is that you shouldn’t care about your future self at all. Yes, we do care about our future selves, because we evolved to care about our future selves, because that serves the interests of our genes. But that doesn’t mean this is correct. Parfit goes back and forth and eventually concedes that this view is hard to refute.

This “ultimate selfishness” becomes a bit absurd, though. Say I decide that I’m just a momentary puff of qualia and there’s no me, so I might as well screw over my future self. So, I go and buy some heroin. But as I’m about to shoot up, I think—why bother? The person experiencing the high in 3 seconds isn’t me. How unexpected—mixing self-interested behavior with a belief that the self doesn’t exist yields strange results!

If you’re not completely self-interested, then things are more interesting. Say you hate brushing your teeth. You might decide to skip brushing and accept the consequences later. But do you have the right to do that, if your older self is a different person?

Similarly, is prison moral? How can we make someone suffer for a crime done by a much younger person? This can only be justified on consequentialist grounds, e.g. that it would deter crimes. An extreme view is that even if we believe it must be done for the good of society, we should “apologize” to an older person for the injustice of punishing them for something their younger self did.

Parfit also talks about the morality of abortion. Consider two snapshots in time:

- A sperm is nearby an egg, about to fertilize it.

- Nine months later, a baby is born.

Asking “when did a person start to exist?” is like our earlier thought experiments. Some gametes combined and slowly grew into a baby and that’s a full description of what happened. Asking when the person started to exist has no clear answer because personhood is not an all-or-nothing quality.

(That’s not to say that wouldn’t shouldn’t give this question an answer. I wish Parfit gave “empty” questions a less derogatory-sounding name. It’s a useful concept and it would nice to say “that question is empty” without sounding like you think the question is stupid or not worth answering.)

Parfit also considers how these ideas intersect with utilitarianism: On the one hand, they reduce the scope for compensation. If I hurt you now but pay you compensation later, that doesn’t really deliver justice to the version of you that was hurt. On the other hand, they also decrease the scope of “distributive” principles. You might claim that it’s important that everyone is equally happy, but but what does “equality” mean if people aren’t separate?

How does this leave utilitarianism overall? I think it’s basically fine? The main practical difference seems to be that you should think of your future self as a different person, but in many versions of utilitarianism that doesn’t change much.

Reading all this I was left with a niggling doubt. It’s hard to express, but here’s my best attempt: Say the self doesn’t exist and I’m atoms with no boundaries between people et cetera. Great, but isn’t it still true that it feels like I’m a single being, and doesn’t that require explanation? I’m pretty sure this question is called the unity of consciousness and smart people have been agonizing over it for hundreds of years with no clear resolution, or even a very clear way of talking about it. Reality is a strange place.

Believing it

Do you find these ideas hard to accept? I certainly do.

Refreshingly, Parfit admits that he can’t fully accept them either. He’s convinced on an intellectual level, but when he imagines himself in the teletransportation room, he isn’t sure if he would press the button.

In some ways, “personal identity does not exist” sounds grim and nihilistic. But I think “liberation from the self” is comforting. For one thing, it gives a humane way to think about long-term decisions: Think of your future self as a different person, and be kind to that person.

For another thing, it gives a graceful way to think about mortality. I can’t put this any better than Parfit did:

My life seemed like a glass tunnel, through which I was moving faster every year, and at the end of which there was darkness. When I changed my view, the walls of my glass tunnel disappeared. I now live in the open air. There is still a difference between my life and the lives of other people. But the difference is less. Other people are closer. I am less concerned about the rest of my own life, and more concerned about the lives of others.

[…] My death will break the more direct relations between my present experiences and future experiences, but it will not break various other relations. This is all there is to the fact that there will be no one living who will be me. Now that I have seen this, my death seems to me less bad.

So that’s part three of the book. In part one (covered previously) Parfit showed how moral theories can eat themselves. I haven’t (yet?) covered part two, where he talks about time or part four where he talks about future generations and population ethics.