Here’s something that seems weird:

- More educated people are more often Democrats.

- Richer people are more often Republicans.

- Richer people tend to be more educated.

Don’t believe me? Here, I made some figures.

(All data comes from the General Social Survey for 2016-2022, variables income16, partyid, and degree.)

All three facts seem plausible. But how can they be true at the same time? Arguably Pierre Bourdieu explained this 45 years ago as part of his theory of how taste and class interact.

Classes in space

So what is class? My favorite idea from Bourdieu is that maybe it can’t be captured with any single quantity. If you just think about people as being “upper-class” or “lower-class”, your mental model of the world will always be incomplete, no matter how you define those terms.

Now, to nitpick at language for not being infinitely precise is easy—and usually annoying. But Bourdieu doesn’t just complain. He offers a new model.

His idea is that class is about resources. But there are different kinds of resources. Since cultural knowledge is useful, “cultural capital” is a resource, just like economic capital. So if you want to understand class, you have to think about not just the total resources, but also the fractions.

It’s a sign of Bourdieu’s influence that you can talk about “cultural capital” today and people will sense what you mean, even if they never heard that term before. He also invented or popularized other capitals like political, symbolic, and social.

Anyway, let’s restrict things to just cultural and economic capital. Then the first axis of class is the sum of the two:

Imagine a successful but poorly paid journalist, and a McDonald’s franchise owner who—in this crude stereotype—doesn’t care much for books or wine or international travel. The latter probably makes more money. But who is “higher class”?

For extra profoundness, Bourdieu prefers to rotate this graph 45 degrees to the left and drop the original axes. This is the orientation we’ll use going forward.

The stuff we like

As you may recall, Bourdieu thinks we acquire tastes based on our life trajectories, and this helps perpetuate class. Upper-class people get access to upper-class culture early in life, which helps them appreciate upper-class stuff, fit in with upper-class people, do well in life, and repeat the cycle with the next generation.

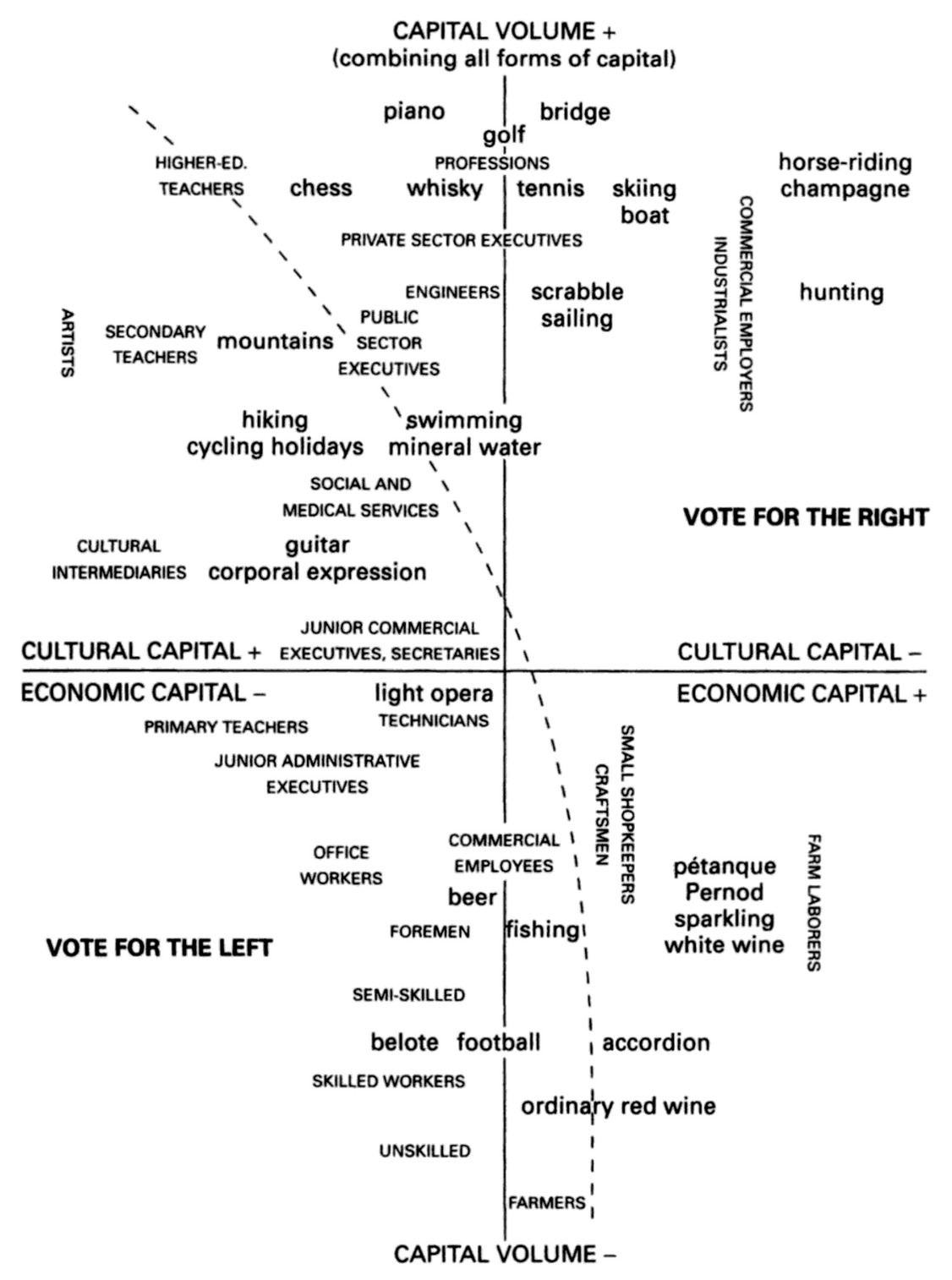

How do we update this theory if class is two-dimensional? Bourdieu says it still holds, but your tastes depend on where you are on both axes. Bourdieu gave evidence for this by doing surveys and finding things favored by people in different parts of class-space:

| mostly cultural capital | roughly equal | mostly economic capital | |

|---|---|---|---|

| high total capital | Warhol, Kandinsky, avant-garde festivals, chess, foreign languages, flea market, mountains | golf, whiskey, boat, air travel, sailing, second home, antique shops | art collection, hotel holiday, auction, historical narrative, hunting |

| medium total capital | monuments, library, surfing, Van Gogh, jeans, modern jazz, champagne | photography, Beatles, circus, picnics, light opera, swimming, salad, mineral water | variety shows, music-hall |

| low total capital | (nothing) | do-it-yourself, beer, sewing, fishing, watching sports, TV, bacon, ordinary red wine | non-champagne sparkling white wine, accordion, love stories |

He also suggests different occupations that fall into different regions:

| mostly cultural capital | mixed | mostly economic capital | |

|---|---|---|---|

| high total capital | secondary teachers, college teachers, artistic producers | professions, engineers, private-sector executives | industrialists, commercial employers |

| medium total capital | cultural intermediaries, primary teachers | social and medical services, craftsmen, junior executives, secretaries, technicians | small shopkeepers, craftsmen |

| low total capital | (no one) | office workers, foremen, farmers | farm labourers |

This table is laid out like the last drawing, with rows for the first axis of class and columns for the second. So the upper-left cell is people with high total capital, most of which is cultural, while the lower-right cell is people with low total capital, most of which is economic. If some of those look odd (sparkling white wine, hunting), remember this was done for 1960s France.

Also, pop quiz: Do you know what L’Aurore is? How about Xenakis? Vasarely? Pétanque? I didn’t, so I didn’t list them above. (Pétanque looks fun.) There were also many things that I knew, but have no idea what they meant in France 60 years ago (Scrabble, whiskey, Buffet). I didn’t list those either.

The lower-left cell is empty. That’s because Bourdieu thinks there are almost no such people. If you’re starving from a lack of food and “starving for better art”, I guess you prioritize the literal starving.

So… why? Why do people in different parts of class-space like different stuff? I think three forces are definitely at play:

- Some stuff is expensive, and some people can’t afford it. I haven’t yet been able to indulge my passion for sports-team collection.

- Everyone is constantly (if unconsciously) engaged in a game to try to appear higher on the vertical axis and prevent others from doing the same.

- Randomness and historical contingency.

What’s less clear to me is if there’s some other force. Bourdieu theorizes that lower-class people have a Taste for Necessity. If you work outside in the cold all day, he thinks you’d rather come home and eat something simple and familiar, rather than needing every meal to be an adventure and demonstration of how amazing you are. Maybe, but I wasn’t convinced.

On politics

Now Bourdieu makes a surprising move: He suggests that your position in class-space also influences your political views. Basically, his theory is that the (nonexistent) people in the lower-left favor the left, while the people in the upper-right favor the right.

I think this curve is… still basically correct today? Certainly it’s consistent with the education/income/party riddle we started with. The shape of the curve might have wiggled around a bit, but it’s still amazing that the basic pattern should hold in different countries 60 years later.

But still, why? Why does the dotted line have that shape? Take two contrasting models:

- Political views are semi-arbitrary preferences, no different from surfing or bacon. People adopt “political tastes” in the same way they adopt tastes for food or fashion.

- Something deeper is happening, so people in different parts of class-space are naturally drawn to different political views.

I’m sure the second model is at least partly right, in that we respond to self-interest and life experience. If you get a higher-paying job, you tend to sympathize more with the idea that income taxes are bad. If you love museums and the life of the mind, you’ll tend to think the government should spend more on museums and schools.

But surely the first model is at least partly right, too. Some would argue for it based on the fact that political views are correlated even on unrelated issues—Why should your view on when personhood begins in pregnancy be related to your view on the relative importance of climate change vs. economic growth? It seems too random to be explained by life or self-interest.

I think that argument is over-stated, because people’s views on different issues just aren’t that correlated, and who’s to say what is an “unrelated issue”.

Still. People tend to hang out with other people from nearby parts of class-space, and get their news from similar sources. Surely this helps their political views converge, in a way that’s not that different from what happens with fashion or food.

Bourdieu spends a ton of time on this, but he’s mostly describing the current situation. I wasn’t able to figure out which of the above two models he thinks is more important, or if he even has a position on that.

I also think there’s something important missing from Bourdieu’s picture: Draw it in a simplified way like this:

So allow me to modestly suggest a revision to Bourdieu’s theory. I think it should look something like this:

Everyone seems to blame the internet for our ever-increasing polarization. It would be funny if the true culprit were education and economic growth.

This post is part of a series.

- Part 1: Bourdieu’s theory of taste: a grumbling abrégé

- Part 2: Your tastes are a point in space

- Part 3: Taste games