Here are some claims about how grades (GPA) and test scores (ACT) predict success in college.

In a study released this month, the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research found—after surveying more than 55,000 public high school graduates—that grade point averages were five times as strong at predicting college graduation as were ACT scores. (Fortune)

High school GPAs show a very strong relationship with college graduation despite sizable school effects, and the relationship does not differ across high schools. In contrast, the relationship between ACT scores and college graduation is weak-to nothing once school effects are controlled. (University of Chicago Consortium on School Research)

“It was surprising not only to see that there was no relationship between ACT scores and college graduation at some high schools, but also to see that at many high schools the relationship was negative among students with the highest test scores” (Science Daily)

“The bottom line is that high school grades are powerful tools for gauging students’ readiness for college, regardless of which high school a student attends, while ACT scores are not.” (Inside Higher Ed)

See also the Washington Post, Science Blog, Fatherly, The Chicago Sun Times, etc. All these articles are adaptions of a press release for Allensworth and Clark’s 2020 paper “High School GPAs and ACT Scores as Predictors of College Completion”.

I understood these articles as making the following claim: Standardized test scores are nearly useless (at least once you know GPAs), and colleges can eliminate them from admissions with no downside.

Surprised by this claim, I read the paper. I don’t want to be indelicate, but… the paper doesn’t give the slightest shred of evidence that the above claim is true. It’s not that the paper is wrong, exactly, it simply doesn’t address how useful ACT scores are for college admissions.

So why do we have all these articles that seem to make this claim, you ask? That’s an interesting question! But first, let’s see what’s actually in the paper.

Test scores are not irrelevant

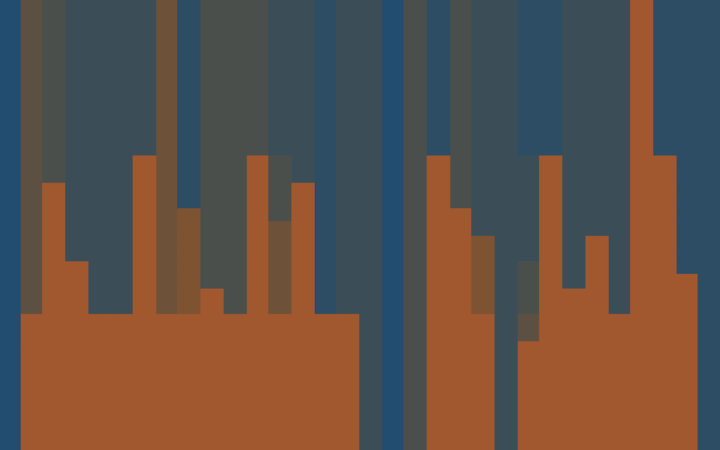

The authors got data for 55,084 students who graduated from Chicago public schools between 2006 and 2009. Most of their analysis only looks at a subset of 17,753 who enrolled in a 4-year college immediately after high school. Here’s the percentage of those who graduated college within 6 years for each possible GPA and ACT score:

The light colors in the upper-right show that students with high ACT scores and high GPAs graduate at high rates. The dark colors in the lower-left show that students with low ACT scores and low grades graduate at low rates. The medium colors in the upper-left and lower-right show that when one (of ACT score and GPA) is high but the other is low, students graduate at medium rates.

We can also visualize this by plotting each row of the above matrix as a line. This shows how graduation rates change with ACT score for each fixed GPA.

It doesn’t appear that ACT scores are useless. But let’s test this more rigorously.

Test scores are highly predictive

The full dataset isn’t available, but since we have the number of students in each ACT / GPA bin above, we can create a “pseudo” dataset, with just a small loss of precision. I did this, and then fit models to predict if a student would graduate using GPA alone, ACT alone, or with both together. (The model is cubic spline regression on top of a quantile transformation.)

Here’s the model that uses ACT only:

Heres’ the model that uses GPA only:

And here’s the model that uses both:

To measure how good these fits are, I used cross-validation—I repeatedly held out 20% of the data, fit one of the above models to the other 80%, and then measured how well the model predicted graduation for the students in the held-out data. You can measure how accurate the predictions are, either as a simple error rate (1-accuracy) or as a Brier score. I also compare to a model using no features at all, which just predicts the base rate for everyone.

| Predictors | Brier | Error |

|---|---|---|

| Nothing | .249 | .491 |

| ACT only | .219 | .355 |

| GPA only | .210 | .330 |

| both | .197 | .302 |

It’s true that GPA does a bit better than the ACT. But note that the difference between the 3rd and 4th lines above is larger than the difference between the 2nd and 3rd lines. If you care about the difference in accuracy between GPA and ACT, then you should care even more about the difference between (GPA only) and (GPA plus ACT). It’s incoherent to simultaneously claim that the GPA is better than the ACT and also that the ACT doesn’t add value.

I repeated this same calculation with other predictors: logistic regression, decision trees, and random forests. The numbers barely changed at all.

Here’s logistic regression with almost no regularization: (These don’t look perfectly linear because of the quantile transform.)

Here’s trees, grown to maintain at least 10 data in each leaf.

Here’s random forests:

Here’s the error rates of all the methods:

| predictor | spline | logreg | trees | forests |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT only | .355 | .353 | .355 | .355 |

| GPA only | .329 | .330 | .330 | .330 |

| both | .301 | .303 | .302 | .303 |

And here are the Brier scores:

| predictor | spline | logreg | trees | forests |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT only | .219 | .219 | .219 | .219 |

| GPA only | .210 | .210 | .210 | .210 |

| both | .197 | .197 | .197 | .197 |

Still, these are all just calculations based on the data.

What the paper actually did

For each student, they recorded three student variables:

- Gender

- Ethnicity (Black, Latino, Asian)

- Poverty (average poverty rate in the student’s census block)

For the students who enrolled in a 4-year college, they recorded four college variables:

- The number of students at the college

- The percentage of full-time students

- The student-faculty ratio

- The college’s average graduation rate

They standardized all the variables to have unit mean and unit variance (except for gender and ethnicity since these are binary). For example, GPA is 0 for someone with the average grades, and GPA is -2 for someone 2 standard deviations below average.

They also included squared versions of GPA and ACT, GPA2 and ACT2. These are never negative and larger for any student who is unusual either on the high or low end. They do this because the relationship is “slightly quadratic”, which is reasonable, but it’s not clear why the other variables don’t get a squared version.

With this data in hand, they fit a bunch of models.

First, they predicted graduation rates from grades alone. Higher grades were better and the relationship was strong. There’s nothing surprising here, so let’s skip the details.

Second, they predicted graduation rates from ACT scores alone. Higher ACT scores were better. Again, let’s skip the details.

Third, they predicted graduation rates from grades, student variables, and variables for the college the student enrolled at. This model produces a “likely-to-graduate” score for each student using the weights visualized below. (Student background variables are in red and college variables are in green.)

The “likely-to-graduate” score becomes a probability after a sigmoid transformation. If you’re not familiar with sigmoid functions, think of them like this: If a student has a score is X then graduation probability is around .5 + ¼ × X. For larger X (say |X|>1) scores start to have diminishing returns, since probabilities must be between 0 and 1.

For example, the coefficient for (male) above is -.092. This means that a male has around a ¼ × 9.2% = 2.3% lower chance of graduating than an otherwise identical female. (For students with very high or very low scores the effect will be less.)

In this model, the two biggest factors are GPA, and the average graduation rate at the college the student enrolls at.

Fourth, they predicted graduation rates from ACT scores, student variables, and college variables.

The dependence on ACT is less than the dependence on GPA in Model 3. However, the dependence on student background and college variables is much higher.

Here, the largest factor by far is the college graduation rate.

Fifth, they predicted graduation rates from GPAs, ACT scores, student variables, and college variables.

Here, there’s minimal dependence on ACT, but a small negative dependence on ACT2, meaning that extreme ACT scores (high or low) both lead to lower likely-to-graduate scores. College graduation rate remains important.

Does that seem counterintuitive to you? Remember, we are taking a student who is already enrolled in a particular known college and predicting how likely that are to graduate from that college.

Sixth, they predicted graduation rates from the same stuff as in the previous model, but now adding mean GPA and ACT for the student’s high school.

In this model they also now standardize some variables relative to each high school. I couldn’t figure out exactly what they were doing or what variables were affected by this change. My guess is that it’s just for GPA and the SAT, but I’m not totally sure.

What this says about how to do college admissions

I mean… not much?

These models take a student with a certain GPA, ACT score, and background who is accepted to and enrolled at a given college. Then they try to predict how likely that student is to graduate.

It’s true that these models have small coefficients in front of ACT. But does this mean ACT scores aren’t good predictors of preparation for college? No. ACT scores are still influencing who enrolls in college and what college they go to. These models made that influence disappear by dropping all the students who didn’t go to college, and then conditioning on the college they went to.

These models don’t say much of anything about how college admissions should work, for three reasons.

First, these models are conditioning on student background. Look at the coefficients in Model 5. Are we proposing to do college admissions using those coefficients? Meaning we would penalize men and poor students relative to women and rich students with the same grades and test scores? Come on.

Second, test scores influence if students go to college at all. This entire analysis ignores the 67% of students who don’t enroll in college. The paper actually does a model of how likely a student is to go to college and confirms that ACT are a strong predictor.

Many factors influence if a student goes to college. Do they want to? Can they get in? Can they afford it?

You might say, “Well of course the ACT is predictive here—colleges used it for admissions.” Sure, but that’s because colleges thought it gauges preparation. It’s possible they were wrong, but… isn’t that kind of the question here? It’s absurd to assume the ACT isn’t predictive of college success, and then use that assumption to prove that the ACT isn’t predictive of college success.

Third, for students who go to college, test scores influence which college they go to, and more selective colleges have higher graduation rates. Here’s three private colleges in the Boston area and three public colleges in Michigan.

| College | acceptance rate | average graduation rate |

|---|---|---|

| Harvard University | 5% | 98% |

| Northeastern University | 18% | 85% |

| Suffolk University | 84% | 63% |

| University of Michigan - Ann Arbor | 23% | 92% |

| Michigan State University | 71% | 80% |

| Grand Valley State University | 83% | 60% |

The paper also builds a model for the students who go to college to try to predict the graduation rate of the college they end up at. Again, GPA and ACT scores are about equally predictive.

Of course, you could also drop the student background and college variables, and just predict college graduation from GPA and ACT. But remember, I did that at the start of this post, and ACT was extremely predictive.

Alternatively, I guess you could predict how likely a student is to graduate using student background but without using the average graduation rate at the college the students went to. I doubt this is a good idea or a realistic idea, but at least it’s causally possible that colleges might use such a model to do admissions.

Why didn’t the authors build such a model? Well… Actually, they did.

Unfortunately, this hidden away on a corner of the paper, and no coefficients are given other than for GPA and ACT. It’s not clear if high-school GPA or ACT are even included here. The authors were not able to provide the other coefficients (nor to even acknowledge my numerous polite requests notthatimbitteraboutit).

The laundering of unproven claims

What happened? Fundamentally, what the paper did is OK. It fits some models to some data and gets some coefficients! Interpreted carefully, it’s fine. And the paper itself never really pushes anything beyond the line of what’s technically correct.

Somehow, though, the second the paper ends, and the press release starts, all that is thrown out the window. The paper says “ACT scores definitely predict college graduation, but they don’t seem to give much extra information if you already know if and where a student is going to college, plus their sex, ethnicity, and wealth”. In the press release, this becomes “ACT scores don’t predict college success”.

To be fair, a couple hedges like “once school effects are controlled” make their way into the articles but are treated as a minor technical asides and never explained.

So let’s separate a bunch of claims:

-

It might be desirable to reduce the influence of test scores on college admissions.

-

It might be that test scores don’t predict college graduation rates.

-

It might be that test scores only predict college graduation because selective (and high graduation-rate) colleges choose to use them in admissions.

-

It might be that if selective colleges stopped using test scores in admissions, test scores would no longer predict college graduation.

I’m open to claim #1 being true. If you believe #1, it would be convenient if #2, #3, and #4 were true. But the universe is not here to please us. #2 is not just unproven but provably false. This paper gives no evidence for #3 or #4. Yet because these claims were inserted into the public narrative after peer review, we have a situation where the paper isn’t wrong, yet it is being used as evidence for claims it manifestly failed to establish.

Journals don’t issue retractions for press releases.

A field guide

The paper has a number of ambiguities, undefined notation and straight-up errors. If you try to read it, these might throw you off (or make you wonder about Educational Researcher's review process). I've created a guide to help you on your way.

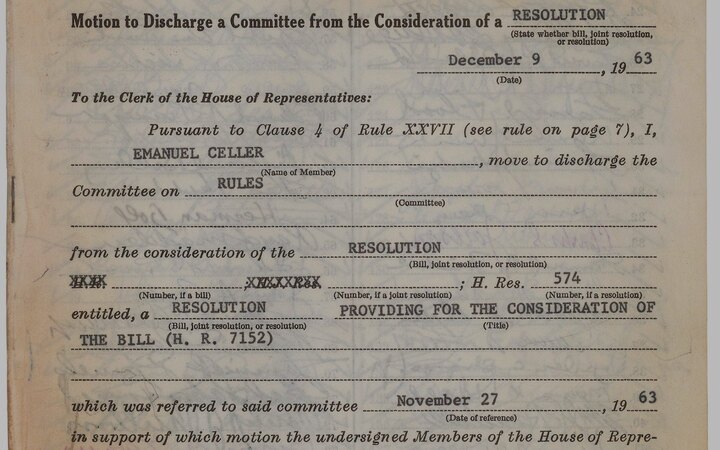

The equations for the models in the paper look like this:

If you want to understand this, you face errors, undefined notation, and the fact that the actual statistical methodology is never explained. First, let’s talk about the errors/typos:

- There’s a a pair of missing parenthesis on the left.

- The first sum makes no sense, since (S)ij doesn’t depend on s. I think that this should be (S)si instead.

- The final sum makes no sense, since (C)ij doesn’t depend on c. I think that this should be (C)cj instead.

- B0j is a mistake. It should be β0j.

If we fix those errors, we get this corrected model:

Next, let’s talk about undefined notation. At no point does the paper define i, j, or rij. (Undefined notation isn’t as bad as it sounds, these are probably cultural knowledge in the authors’ community.) This makes it tricky to decode, but here’s my best attempt:

- The left-hand side is the “score” for student i who happens to be in high-school j. You transform that score to a probability through the sigmoid transformation, since score = log(p/(1-p)) is equivalent to p=σ(score).

- S1i, …, S5i are the background variables for that student. (Gender, ethnicity, poverty.)

- (ZGPA)ij is the student’s GPA, standardized to have zero mean and unit variance. (Called a “z-score”)

- (ZGPA2)ij is the square of (ZGPA)ij. (Don’t get triggered by the location of the parentheses.)

- (C)8j, …, (C)11j are the institutional variables for college j (size, % full time, student/faculty ratio, mean graduation rate).

- The β variable are the learned coefficients. The coefficients for the intercept and GPA terms vary by school and are fit as part of a multilevel model, while the others are fixed.

- rij, u0j, u6j, and u7j are residuals.

Frankly, there’s still some issues here, but I can’t be bothered trying to fix anything else.

Third, the paper never explains what methodology they use to take a dataset, and estimate the parameters of the above model. My guess is that the algorithm is maximum-likelihood. But using maximum-likelihood requires a prior for all the residual terms. The paper never says what that is. Probably a standard Gaussian? Again, this might be “obvious” to the typical reader of this paper, but if the journal is issuing press-releases, shouldn’t they make a cursory attempt to make the paper readable by general audiences?

Finally, a small thing. Their Table 1 lists the ACT ranges as 0-13, 14-16, 16-17, which doesn’t make sense because it repeats 16. I think 14-16 should be 14-15, so I treated it like that above.