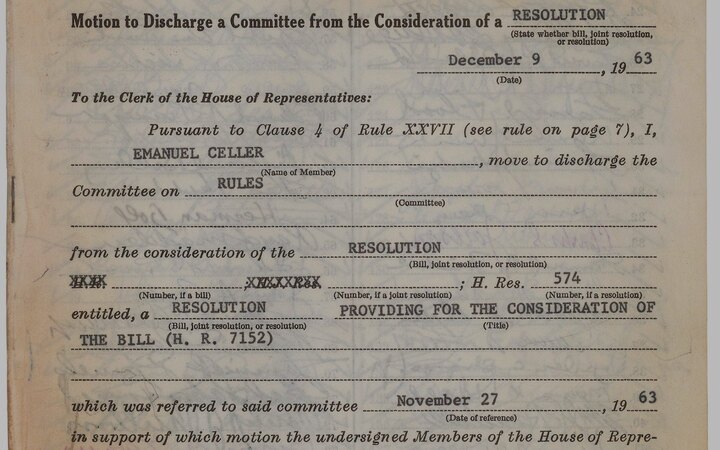

We want to know if things are fair. Do some groups of people tend to get a raw deal in company hiring or university admissions or court sentences?

There seems to be an obvious way to answer such questions: Get some data and “check” for bias. But different people often get different results, even when looking at the same data. What’s going on?

What’s going on is the whole strategy is doomed. It’s counterintuitive, but you usually can’t determine bias this way. The problem boils down to that in order to “check” for bias you must do something to your data called stratification. This can totally change the results, and there’s no single best way to do it.

An experiment

Let’s do a thought experiment. You live in a city inhabited by blue people and red people. There are constant debates about if police are biased against either of these groups. Eventually, you decide to take action. You find 1024 blue men and 1024 red men, give each a suspicious looking stack of $20 bills and tell them to jog outside for an hour while holding the stack. Finally, you count the number that are arrested in each group. (You have a very good relationship with your local IRB.)

Phase 1

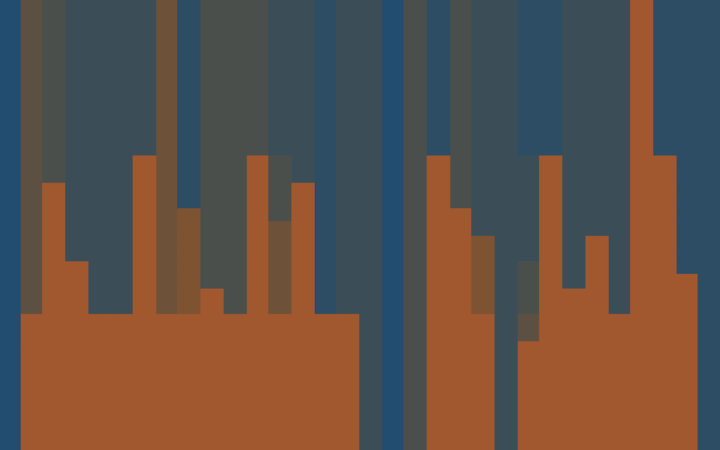

So you run the experiment, and these are the results:

| total | # arrested | % arrested | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blue | red | blue | red | blue | red |

| 1024 | 1024 | 232 | 280 | 22.7 | 27.3 |

More reds were arrested than blues. Does this show police bias against reds?

Phase 2

You show your data to a friend. She notices that the blue men in your population were more often old (over 35) while the red men were more often young (35 or less). In particular, your data has these demographics:

| age | blue total | red total |

|---|---|---|

| old | 640 | 384 |

| young | 384 | 640 |

She re-does your analysis separately for young and old men. The results are as follows:

| age | total | # arrested | % arrested | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blue | red | blue | red | blue | red | |

| old | 640 | 384 | 84 | 44 | 13.1 | 11.5 |

| young | 384 | 640 | 148 | 236 | 38.5 | 36.9 |

Now this suggests a bias against blue men. The police arrest young blue men more often than young red men, and similarly for the old. The reason the previous analysis suggested a bias against red men is that more of them are young.

Does this now show that the police are biased against blues?

Phase 3

Your friend pokes at the data some more. She points out that reds are more likely to live in Riverview, while blues are more likely to live in Pineway. Specifically, you have these demographics:

| where | age | blue total | red total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pineway | old | 384 | 128 |

| Pineway | young | 256 | 256 |

| Riverview | old | 256 | 256 |

| Riverview | young | 128 | 384 |

She re-does the analysis for each location / age group. These are the results:

| where | age | total | # arrested | % arrested | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blue | red | blue | red | blue | red | ||

| Pway | old | 384 | 128 | 70 | 26 | 18.2 | 20.3 |

| Pway | young | 256 | 256 | 110 | 114 | 43.0 | 44.5 |

| Rview | old | 256 | 256 | 14 | 18 | 5.5 | 7.0 |

| Rview | young | 128 | 384 | 38 | 122 | 29.7 | 31.8 |

In each age-location group, reds were more often arrested than blues. The difference from the previous analysis is that blues tend to live in Pineway, and police more often arrest people in Pineway.

This suggests a bias against reds. But, given how things have changed in the past, something feels off…

Phase 4

Sweating, you ask your friend, “Now are we done?”

She says, “Almost! I just noticed that clothing seems to be a factor! Reds tend to wear joggers while blues tend to wear shorts. Just give me a second…”

She re-does the analysis yet again, with the following results. (You may need to scroll the table horizontally.)

| attire | where | age | total | # arrested | % arrested | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blue | red | blue | red | blue | red | |||

| shorts | Pway | old | 224 | 32 | 35 | 5 | 15.6 | 15.6 |

| shorts | Pway | young | 160 | 95 | 65 | 39 | 40.6 | 40.6 |

| shorts | Rview | old | 160 | 96 | 5 | 3 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| shorts | Rview | young | 96 | 160 | 27 | 45 | 28.1 | 28.1 |

| joggers | Pway | old | 160 | 96 | 35 | 21 | 21.9 | 21.9 |

| joggers | Pway | young | 96 | 160 | 45 | 75 | 46.9 | 46.9 |

| joggers | Rview | old | 96 | 160 | 9 | 15 | 9.4 | 9.4 |

| joggers | Rview | young | 32 | 224 | 11 | 77 | 34.4 | 34.4 |

Now, the percentages are exactly the same in each group. The police tend to arrest young men in Pineway wearing joggers. They tend not to arrest old men in Riverview wearing shorts. All the racial differences you saw before might be due to correlations between race and age, neighborhood, and attire, not because of race itself.

Phase 5

You tell your friend “Well done! You’ve resolved it. It’s getting late, I think I’ll be going…”

As you edge towards the door she says “Yeah, goodnight, let’s do this again! But before you leave, I did notice that some people wear headphones and some don’t…”

If you’re familiar with Simpson’s paradox, this is all basically an example of a “recursive” Simpson’s paradox.

Summary

What went “wrong” in this experiment? Suppose you gather data on police interactions with people of a single race. No one would be surprised if the statistics are different with respect to the young vs. old or urban vs. rural or rich vs. poor or churchgoers vs. nonreligious. It would be surprising if there weren’t differences.

Let’s say you want to use observational data to prove police are biased against red people. To do this, you need to split up all red and blue people into subgroups (“strata”) in such a way that each subgroup of red people is “exactly the same” as the corresponding subgroup, except for their race.

This is basically an impossible task. Human beings are complicated and multidimensional. To a first approximation, race is correlated with everything. There’s just too many attributes to firmly establish that any observed difference is really due to race and not to something else that’s correlated with race. However much you try to split people up, there will still be remaining differences between each “red group” and each “blue group” you haven’t accounted for. For the same reason, you can’t use observational data to prove there isn’t bias.

If you want to measure fairness, you need to intervene. We’ll discuss that more next time.

This post is part of a series on bias in policing with more still to come.

- Part 1: Your ratios don’t prove what you think they prove

- Part 2: The veil of darkness

- Part 3: Policy proposals and what we don’t know about them

- Part 4: Why fairness is basically unobservable (This post)