You’ve probably heard about the potato diet. If not, here it is:

- Eat potatoes.

- As many as you want.

- Oil and salt are OK.

- Don’t eat other stuff.

I thought this sounded delightfully absurd so I tried it for a few weeks. Here are some observations.

1. It’s not totally insane

Say you’ve had a huge meal and couldn’t eat another bite. But then—someone offers you iced cream.

You might think: Can I exploit this phenomenon in reverse to lose weight? The obvious thing would be to ban iced cream. But if that helps, maybe you should ban more stuff. If you went really ban-crazy, you’d eventually get to a single food, hopefully something filling and healthy. Voilà: Potato diet.

2. Hunger is complicated

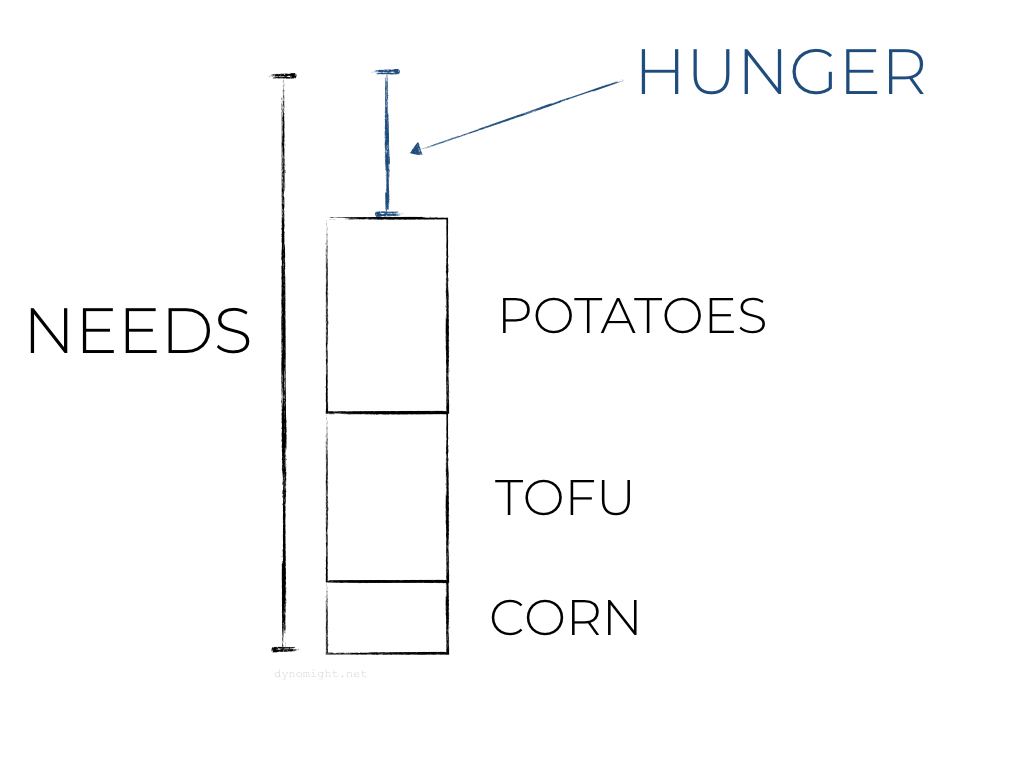

My biggest surprise was how the diet felt. Previously I had a mental model that hunger is the difference between your caloric needs and the total calories you’ve eaten. If the only foods are corn tofu and potatoes, then my old model was

HUNGER = NEEDS - (POTATOES + TOFU + CORN).

I still think this is a decent model, but it’s not quite right.

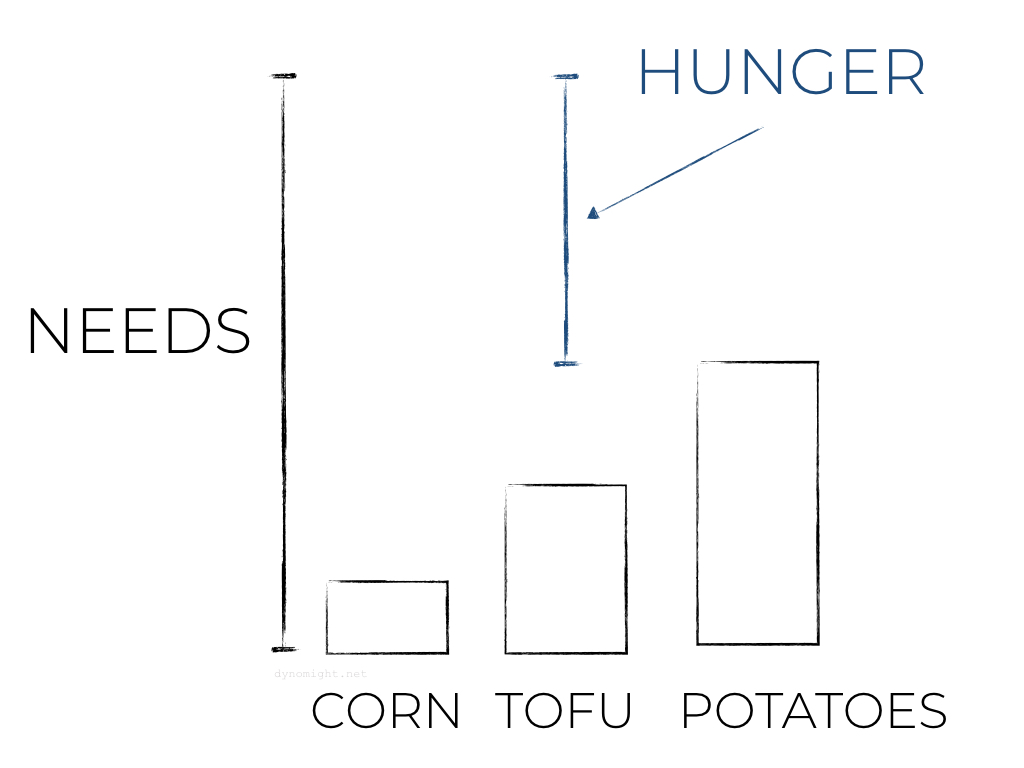

For contrast, imagine that hunger is the difference between your caloric needs and the maximum calories you’ve eaten of a single food:

HUNGER = NEEDS - MAX(POTATOES, TOFU, CORN).

Now, I’m not crazy—I’m sure this second model is wrong and indeed worse than the first one. But I suspect it’s partially right, that the truth is somewhere between the two.

3. Is it easy?

Many people say the potato diet is easy. I for one did not find that to be true! However:

- I always ate as much as I wanted.

- I lost weight.

- I never felt “hunger” exactly.

That sounds easy, right? Why isn’t that easy?

Well, here’s my theory:

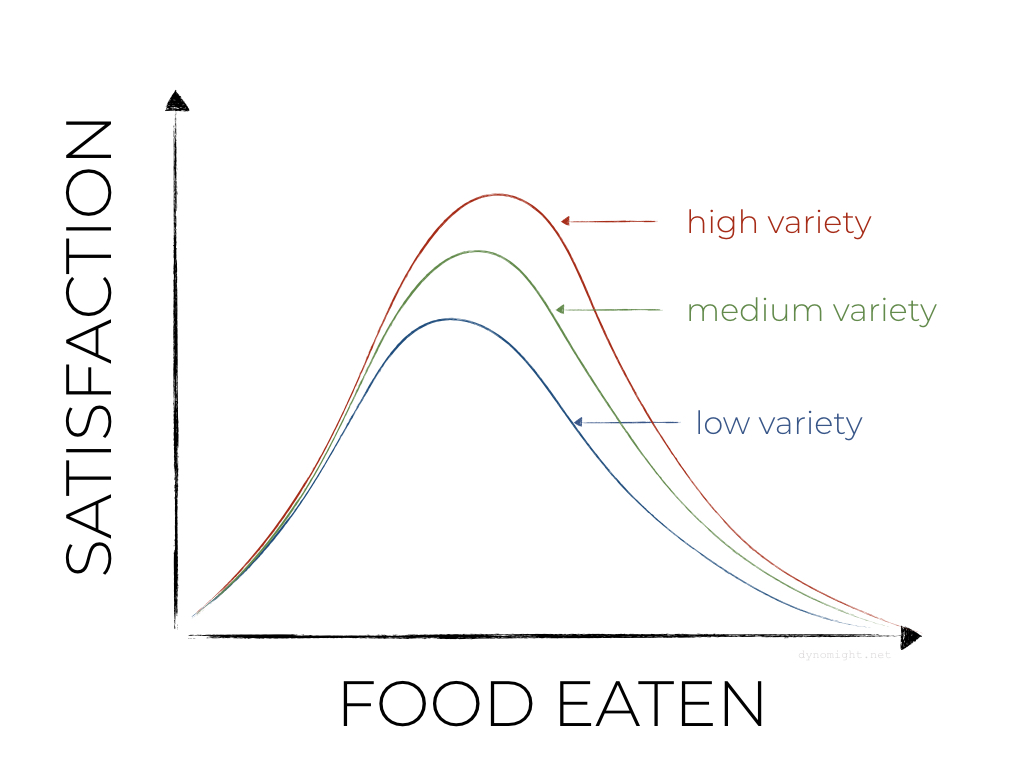

The horizontal axis is how much food you eat and the vertical axis is how satisfied you are. There are different curves for diets with different amounts of variety.

In this model, diets with more variety:

- Are more satisfying.

- Reach their peak satisfaction at a larger amount of food.

Hunger is essentially the desire to move to the right on this graph. I always ate as many potatoes as I wanted, so I never felt “hunger”.

But I felt something—I wanted to eat other foods, to jump onto a higher curve on the above graph. I don’t think this feeling has a good name, but it’s basically what you feel when you have trouble turning down that after-meal iced cream.

4. It’s a pain to cook a lot of potatoes

Slime Mold Time Mold warned us:

The hardest part is the logistics of preparing that many potatoes every single day.

There’s a chance this is important. Suppose your steady-state caloric intake is 2500 per day and you’d like to lose 1 lb (0.45 kg) per week.

Then some simple math shows that you should get 2000 calories per day, which corresponds to around 18 medium golden potatoes.

(Here's the math.)

- To lose 1 lb requires a deficit of 3500 calories per week.

- You would be even if you ate 2500*7=17500 per week

- Thus you should eat 14000 per week

- Thus you should eat 2000 calories per day.

- An medium golden potato has around 110 calories

- 2000/110 = 18.18.

This does become a hassle. However, I have a conspiracy theory that maybe this is a feature in the sense that laziness plus the tedium of preparing all those potatoes leads to eating less.

5. Less decision fatigue

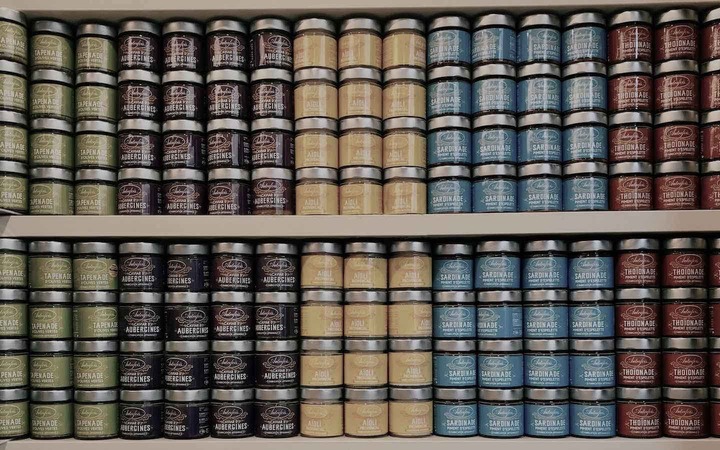

On the other hand, there are so few decisions to make with this diet. Shopping requires no thought: Go to the store and buy all the potatoes. And before cooking, you just choose from a small set of options.

Never in my life have I felt these decisions to be the slightest burden. But it was surprisingly nice to be free of them.

Two hints:

- You will cherish the differences in each variety of potato. Get them all.

- You may want to plan a response for when the cashier asks just what the hell you’re doing. I recommend something confusing and ominous like “in-laws” or “raccoon trouble”.

6. What’s the deal with the glycemic index?

On my long list of life mistakes, one of the most foolish is ignoring the traditional wisdom that carbs make you tired. I only recently started paying attention to this and the gains from avoiding bread and pasta at lunch seem massive.

The typical explanation for this is that bread and pasta have a high glycemic index (GI), meaning that they cause a rapid spike in blood sugar.

Except potatoes didn’t seem to make me tired, and:

| food | glycemic index |

|---|---|

| pasta | 32-64 |

| bagel | 72 |

| white bread | 72 |

| boiled potato | 82 |

| baked potato | 111 |

Either I was getting a placebo effect from bread/pasta or I’m getting a placebo non-effect from potatoes or the whole connection between the glycemic index and energy-levels connection is tenuous. Unsure.

7. Here are some things with similar numbers of calories

Which of these would you rather have to sustain you for a day?

| food | calories |

|---|---|

| 1.5 lb loaf of bread | 1760 calories |

| 5 bacon cheeseburgers | 1715 calories |

| 7.5 avocados | 1755 calories |

| 12 breadsticks | 1820 calories |

| 5 lb / 2.27 kg bag of potatoes | 1735 calories |

8. Predictions

By any conceivable definition, “eat only potatoes” is a fad diet. And the history of dietary ideas leaves a trail of dead rushing out to the horizon. Skepticism is warranted.

Now, I’m not particularly well-read on weight loss and diets, even by the loose standards of pseudonymous internet autodidacts. But I spent some time studying Wikipedia’s list of diets and here’s what I found:

- Low-fat diets work.

- Low-carb diets work.

- Low-protein diets work.

- Mediterranean diets work.

- Ketogenic diets work.

- Gluten-free diets work.

Also: Liquid diets, baby food diets, grapefruit diets, rice diets, carnivore diets, vegan diets.

EVERYTHING WORKS (at least in this short term).

How to explain this? Well, what does everything have in common? Every diet restricts food choices.

Thus, while the potato diet is certainly a fad diet, it’s consistent with the most-proven principle of dieting we have: Restricting food choice causes weight loss. Arguably, the potato diet takes this principle to its logical conclusion.

Thus, I predict with medium confidence that the potato diet is effective at causing short-term weight loss. (I can give a probability of 85% if you want but this still isn’t a real prediction since I haven’t defined “effective”, chosen a timeline, etc.)

At the same time, there’s another hope for the potato diet: That it’s uniquely good at keeping weight off.

The problem is: It’s not really possible to stay on the potato diet long-term. When I talked to some doctors I know (socially) about this, they were alarmed. Now, these were random specialists, and they often gave incorrect reasons (e.g. that potatoes have no protein). I think it’s probably fine for a few weeks. But still: Everyone seems to agree that it’s most healthy to eat a varied diet and a single ingredient is not varied. You can’t eat potatoes forever.

And the evidence seems to be that all other fad diets don’t work to keep weight off long-term. For that to happen, you need to transition to a lower-calorie steady-state diet. It’s possible that some diet could reset your hormone balance so that eating naturally would keep you at a lower weight. But as far as I know, no such diet is known, and I see no reason to think the potato diet will be the first exception.

Thus, I also predict with high confidence that the potato diet is not effective in leading to sustained weight loss.

It’s not that I think the potato diet is bad for keeping weight off, I just guess that it’s irrelevant—all that matters is your steady-state lifestyle after the diet is over.

9. Where does that leave us?

Let’s assume that my predictions are correct, that lots of fad diets (including the potato diet) lead to short-term weight loss, but they don’t do anything long-term. What then?

Obviously, we can try to find long-term diets that make it easy to sustain lower weight. This is important, but we’ve been working on this for a long time, and everyone knows the dire statistics for rebounding after a diet.

So I’ve been pondering an alternative “thermostat” strategy. Say you want to weigh 80 kg. You could do something like this:

- Use a fad diet (e.g. potato) to get down to 80 kg.

- Weigh yourself every morning

- If your average weight over a week ever exceeds 81 kg, spend the next week on the potato diet.

- Repeat forever.

Is there any research on something like this? A key assumption is that you lose weight on the fad diet more quickly than you gain it eating ad libitum—otherwise you’d be spending half your time on a fad diet, which doesn’t seem healthy. Optimistically, “fear of a potato week” might lead you to control portions all the time, meaning you don’t need to Go Potato too often.