I love box-fan based air purifiers. They are cheap, trivial to build, and people around the world have done experiments to show they actually work.

Still, box-fan purifiers have two downsides: They create a lot of noise, and they consume a fair amount of electricity.

I wanted a new design that preserves the best aspects of using a box-fan:

- Cheap.

- Easily built with no tools.

- No proprietary parts.

- Good at purifying the air.

The design should also fix the worst parts of using a box fan:

- Make less noise.

- Use less electricity.

I think I’ve found such a design. Behold, the Cuboid:

Performance summary

I’ve done some experiments comparing this to a box-fan based purifier, using the same filters. Here’s a summary.

| Purifier | Box fan | Cuboid | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fan speed | low | med | high | low | med | high |

| Cost to build | $71.50 | $100 | ||||

| Time to build | 30 s | 5 min | ||||

| PM 2.5 half-life (mins) | 18.4 | 13.2 | 9.6 | 15.1 | 10.3 | 6.9 |

| PM 2.5 CADR (m³/min) | 1.15 | 1.58 | 2.17 | 1.40 | 2.02 | 2.95 |

| Sound level (dB) | 43 | 48 | 55 | 16 | 39 | 51 |

| Power usage (W) | 65.4 | 76.4 | 96.0 | 22.6 | 40.3 | 51.3 |

| Power cost/year ($) | 74.4 | 87.0 | 109.3 | 25.73 | 45.9 | 58.4 |

| Resembles IED | ★☆☆☆ | ★★★☆ | ||||

Less is better for everything except the clean air delivery rate (CADR). The half-life is calculated in a 31 m³ room. Electricity costs assume operation 24 hours/day at 1 kWh = $0.13.

As you can see, the cuboid gives major improvements in noise and electricity consumption, with small regressions in cost, difficulty of construction, and IED resemblance. Particularly on low, the cuboid is very quiet and energy-efficient. Somewhat accidentally, it’s also better at removing particles.

The fan/filter tradeoff

Air purifiers push air through filters. If you’ve ever built a box-fan-based air purifier, you noticed that once you attach HEPA filters, throughput decreases dramatically. If you use a weak fan, it will barely push any air at all.

Fundamentally, if you want to increase purification, you have two options:

- Big fan: Keep the same amount of filter, but run a bigger/faster motor to push air through it faster.

- Big filter: Keep the same fan, but install more filters in parallel. This will decrease the pressure on each of them, meaning more total airflow.

If we want to be quiet and energy-efficient, the choice is clear: Use a relatively weak fan, but with a large filter surface area.

Using more filters has a higher upfront cost — filters aren’t free. However, that extra cost disappears over time. If each filter can remove a fixed amount of particulates before it needs to be replaced, then doubling the number of filters means also doubling the replacement interval.

How to build it

(Contact me if you want the exact products I used.)

Materials used

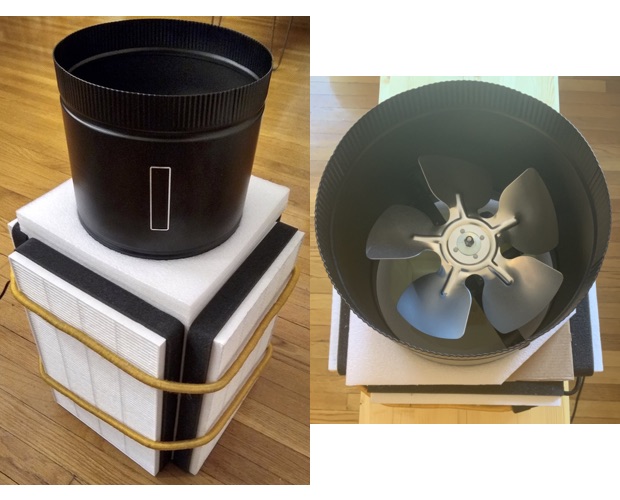

- An 8inch (20.32cm) diameter inline duct booster fan ($30).

- Four HEPA air filters, each approximately 32 cm x 22 cm and 5cm thick ($70 for all).

- Two bungee cords (free).

- Tape (free).

- Two pieces of packaging foam (free).

Inline duct booster fans are fairly weak fans often used to help with grow rooms or range hoods. An inline duct fan would probably perform even better (see the discussion) but at a higher cost. The one I bought is rated to push around 12 m³ of air per minute.

You can use filters and fans of different sizes if you want. All that matters is that the fan has a smaller diameter than the filters (20.32 cm < 22 cm). The pieces of foam also need to be at least as large as the matching dimension of the filter. I just used the foam that my fan was shipped in.

Step 1: Form a column out of the filters

Take the four filters, and assemble them into a vertical structure. Be careful to align the edges as you see in the middle, with two sides slightly “inside” of the other sides.

This column is somewhat unstable, but we’ll deal with that.

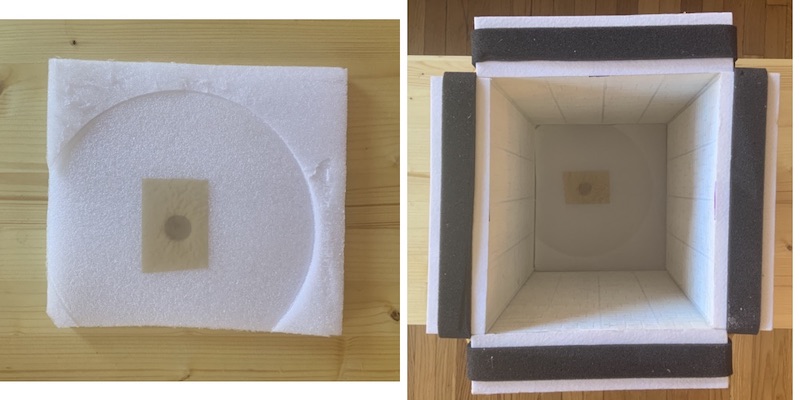

Step 2: Cut out a base for the column

Cut one piece of foam to the size of the square at the bottom of the filter column (I taped over a hole in the foam I used.) Place it at the bottom.

I did this by setting the filters on top of the foam, tracing out the shape with a pencil, and then cutting the foam with scissors. You probably want to err on the side of making it larger and trim if necessary. It should fit firmly so that it’s held in place by the filters.

Strictly speaking, you could also probably skip this step. I did that in an early version and it was OK. However, this adds a lot of stability allows the purifier to work even if it isn’t on top of a flat surface. You could also substitute some other material for the foam.

Step 3: Cut out a base for the fan

Cut another piece of foam so that it supports the fan from below while holding the fan in place. This should be large enough so that that the piece will sit on top of the filters.

As you can see, the foam was missing a corner, which I solved inelegantly by gluing on a piece of cardboard.

Step 4: Set the fan on the filter column

Set the fan+foam on top of the filters, oriented so it will blow air upward, and pull air through the filters.

That’s it, you’re done. The top is only held on by gravity, plus pressure if it’s on. You could obviously make this more stable or beautiful, but I wanted to focus on a design that’s really easy to build.

Cost

The only significant cost is the fan ($30) and the filters ($70 for 4). This is more expensive than a box fan design, where the fan costs $19 and you only need 2 or 3 filters. However, as mentioned above, the cost of extra filters evens out in the long run since they need to be replaced half as often.

Measuring filtering performance

Experimental setup

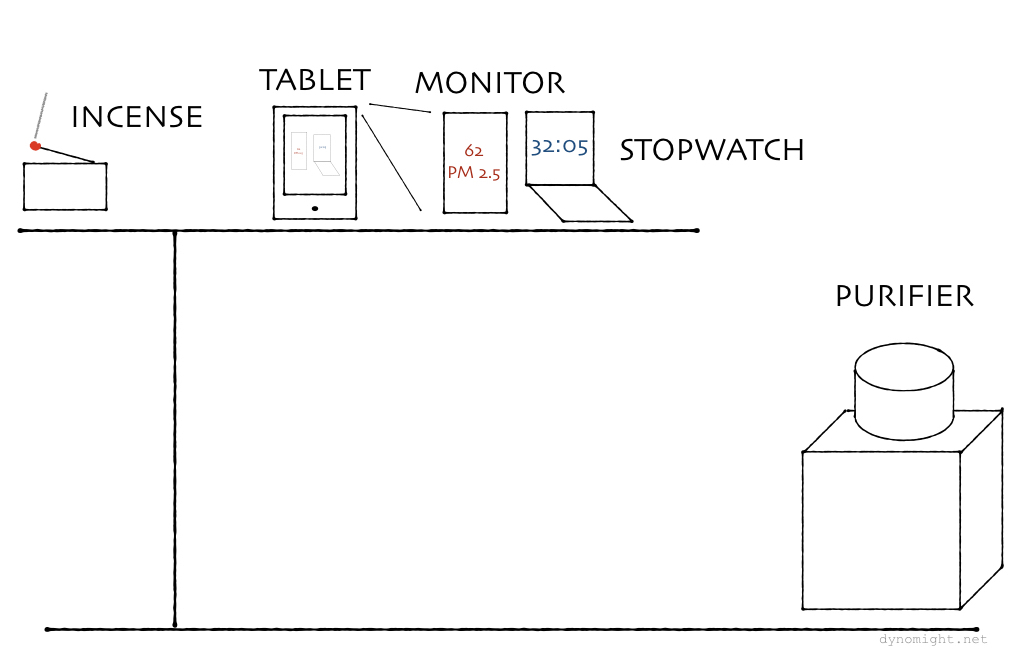

I did experiments in a room with a volume of around 31 m³. To generate smoke, I cut 5 credit-card length sticks of incense and placed them on one end of a table. On the other end of the table, I placed a tablet that took a time-lapse video of a particle counter and a stopwatch. I then manually transcribed the measurements from this video.

The purifier (box fan or cuboid) was on the ground around two meters from the particle counter.

Results

As a comparison, I attached three of the same filters to a box fan (Literally the same filters).

Here are the results with the cuboid. Note that the y-axis is logarithmic. The straight lines indicate that particulates are decreasing at an exponential rate.

Here are the results of the box fan.

You’ll notice two things. First and most importantly, the slopes for the cuboid graphs are steeper. This indicates better performance.

Second, the particles peak at higher values with the cuboid. I believe this is because the incense was near the particle counter on a table, while the purifiers were sitting on the floor 2m away. If the air isn’t disturbed, it takes a while before smoke drifts over the purifier and it actually starts doing anything. However, the box fan creates so much wind that the smoke immediately diffuses around the room and the box-fan purifier essentially gets a “head start”.

While wind seems to help here, it could be harmful in other cases. I discuss this more below.

Fitting exponential curves

The y-axes in the plots above are logarithmic. As you can see from the dotted lines, these are well-fit by straight lines. This is what we’d expect if a fixed fraction of the air were being cleaned per minute.

The dotted lines for each curve show a fit of the form y=a×bᵐ, where y is the level of particulates, m is the number of minutes, and a and b are constants.

We can convert a fit of this type to a half-life: The number of minutes the purifier needs to eliminate half the particles from the air when running in a 31 m³ room. That would be the number of minutes m such that bᵐ = .5. We can solve this equation as m = log(.5) / log(b).

| Purifier | Box fan | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fan speed | low | med | high |

| PM 2.5 fit | 90×.963ᵐ | 90×.949ᵐ | 65×.93ᵐ |

| PM 2.5 half-life (mins) | 18.4 | 13.2 | 9.6 |

| Purifier | Cuboid | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fan speed | low | med | high |

| PM 2.5 fit | 300×.955ᵐ | 280×.935ᵐ | 180×.905ᵐ |

| PM 2.5 half-life (mins) | 15.1 | 10.3 | 6.9 |

Clean air delivery rate calculations

One common way of estimating the performance of purifiers is the clean air delivery rate (CADR). If the air that came out of the purifier had zero particulates, this would just be the volume of air per unit of time.

The fits above were of the form y=a×bᵐ. This means that the number of particulates drops by a factor of b each minute.

Here’s how I calculated the CADR. If the purifier delivered (cleaned air) m³ of clean air in a single minute in a room with a total volume of (all air) m³, then the particulates in a room would drop by a factor of

per minute. We can solve this to find that equation to get that

I measured the dimensions of the room where I did these measurements, arriving at an estimated volume of 31m³. From this, I computed the CADR for each purifier and speed as CADR = 31×(1-b). This gives the following table of CADR rates.

| Purifier | Box fan | Cuboid | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fan speed | low | med | high | low | med | high |

| PM 2.5 CADR (m³/min) | 1.15 | 1.58 | 2.17 | 1.40 | 2.02 | 2.95 |

| PM 2.5 CADR (ft³/min) | 40.5 | 55.8 | 76.6 | 49.2 | 71.1 | 104 |

A recent study from the University of Toronto also measured the CADR of a similar box-fan purifier. They measure around 92 ft³/min. (They don’t give numbers, but there’s a graph where a CADR of 100 ft³/min would be 130 pixels high and the box fan is 100 pixels high.) This is reassuringly close to my estimate of 76.6. I’d put a confidence band of around 20% on my numbers due to the crude measurement of room volume. Also, I used 3 HEPA filters rather than a single MERV 13 filter, so there’s no reason to think true performance is exactly the same.

Measuring noise

I measured noise using the excellent phyphox app on my phone from around 2m away. I didn’t calibrate the measurements, so the absolute values are suspect, but the relative values should be fine. I’m estimating the absolute values off the manufacturer’s claimed noise level for the box fan.

| Purifier | Box fan | Cuboid | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fan speed | low | med | high | low | med | high |

| Sound level (dB) | 43 | 48 | 55 | 16 | 39 | 51 |

It’s quieter across the board (4 dB is noticeable) but the real advantage comes when running on low. The Cuboid is just above the threshold where it’s noticeable across the room, similar to a quiet refrigerator. A Box fan even on low is enough to make conversation or listening to music somewhat less pleasant.

Measuring energy usage

I measured the electricity consumption of each purifier on each fan speed using a standard wattmeter. I estimated the yearly electricity cost by using the average US electricity cost of $0.13 / kWh, and assuming the purifier is run around the clock. Costs around the world vary from around ⅓ as much (Egypt) to around 3× as much (Germany).

Incidentally, I never noticed this before: If a device consumes X watts then running it constantly for a year costs a bit more than $X at average US electricity prices. This coincidence happens because

Discussion

The upper limit

The fan I used is rated to push 12 m³/min of air. However, the CADR is only around ¼ that. In principle this suggests that adding more filters (perhaps a lot more filters) could increase the filtering performance by up to a factor of four, with no extra electricity cost. (I checked: The power usage does not change significantly when the filters are there to slow down the fan.)

Should you bother building a Cuboid?

Box fans have four advantages over the Cuboid. They’re even easier to build. They work with a larger range of filters. Their upfront cost is lower. Finally, you might already have a box fan lying around, or find one on the street or something. It’s unlikely that an extra inline duct booster fan will just fall into your lap.

So when is a Cuboid worth it? I think a box fan is probably fine if you’re just going to run it for short periods of time and don’t mind the noise. But a Cuboid is much better if you will run it for long periods.

One way to measure the quality of a purifier is the amount of air it cleans per unit of power consumed. We can do this by dividing the CADR by the power usage. This gives the following results:

| Purifier | Box fan | Cuboid | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fan speed | low | med | high | low | med | high |

| CADR/power (m³/min/kW) | 17.6 | 20.7 | 22.6 | 61.9 | 50.1 | 57.5 |

The Cuboid does at least 2.4× better everywhere but is 3.5× better when running on low. This is the same setting where the cuboid produces 27 dB (~500 times) less noise.

When is airflow helpful?

A box fan generates much more airflow than the cuboid while having marginally worse filtering performance. That’s because lots of the air it pushes doesn’t go through the filters. Is this is good thing?

We might look at this question more generally. Suppose you have some air purifier. Is it be helpful to add a high-velocity fan in the same room?

To answer that, we have to consider two questions: (1) how close the purifier is to the source of smoke and (2) how close you are to the source of smoke.

-

If the smoke is near the purifier but far from you, then you want to minimize extra airflow. That makes the purifier most effective, and keeps the particles away from you as long as possible.

-

If the smoke is near you but far from the purifier, you want lots of airflow. That reduces the concentration of smoke near you, and gets the purifier doing something as soon as possible. (This is the situation I accidentally created in these experiments.)

In the other situations, it’s really not clear. (Let me know if you have a convincing argument.)

-

If the smoke is near both you and the purifier, the benefit is airflow is unclear. My instinct is that airflow is good because it reduces the peak concentration of particles you breathe. However, it also makes the air purifier less effective. Perhaps it doesn’t really matter?

-

If the smoke is far from both you and the purifier, but you’re close to the purifier, then reducing airflow means the purifier can create a kind of protective bubble around you. This seems good?

-

If the smoke is far from you but you’re far from the purifier, I guess it doesn’t matter? Adding a fan makes the purifier start working faster, but also means you get exposed to the particles faster. In this case the airflow seems to just “push time forward” a bit.

Long-story short, airflow is sometimes helpful and sometimes harmful. The best thing is to have a separate fan that you can turn on or off when the situation dictates.

The competition

There are lots of commercial purifiers out there. Some of these have a similar “can” or “cuboid” design. Some of them claim CADR and power usage numbers that are similar. If you don’t mind the extra cost, probably some of these work fine.

However, the tests I’ve seen don’t inspire confidence. Every time some organization runs a bunch of tests, they find that some of the purifiers work well, some work badly, and almost none of them meet the specs they are claimed to meet. If you take the top pick from the Wirecutter and read user reviews carefully, you’ll see that roughly one person a week reporting that their unit exploded.

Why don’t manufacturers publish tests to show their products work? It’s not that hard – I, random internet person, did it here as a hobby. I think the reality is that people are suckers, and assume (incorrectly) that if they give Dyson $600, they’ll get something in return that works better than a janky DIY device.) I say: Until manufacturers provide evidence, give no quarter.

Advice

If the outdoor air is clean where you live, I suggest you put a purifier in your kitchen and run it on high while cooking (or any other activities that create smoke). If you’re only running it for short periods, electricity consumption is a minor concern. If random noises annoy you, it’s probably not worth running a loud purifier all the time. If you have a purifier that’s quiet and efficient (did I mention I have a design for that?) it’s probably still a net benefit to run it all the time.

If the outdoor air is dirty where you live, I suggest you run a purifier constantly year-round. In fact, you might need to run multiple purifiers in different parts of your home. The health benefits are really quite large and you should take whatever measures are necessary. Here, electricity costs will add up quickly, and noise will be a significant quality-of-life issue. Get purifiers that are quiet and efficient.

Either way, reducing indoor air pollution might be the most effective health intervention you can make. Making up numbers, running might provide 5× the benefit, but it’s at least 25× the effort. All the stuff you put in your body matters, but clean air can be had at low cost and with near-zero willpower. Don’t miss out.

You might ask

Haven’t you spent way more time and money running these experiments than you’ll ever save?

Yeah, probably by a factor of 10.