1.

You’re in love. The two of you want to share the rest of your lives. So, being good game theorists, you have a romantic dinner and plan how to align your interests for mutually beneficial optimal strategic behavior.

Your goals are (1) to Odysseus yourself so that even if you’re momentarily tempted to break up you can’t, and (2) to remove the power of breaking up as a negotiation tactic so that you both invest fully in the relationship.

So you come up with a plan: You’ll make costly commitments by purchasing jewelry, and you’ll sign a contract with the government that intermingles assets and is difficult to unwind. Maybe you’ll even join a religion that says that breaking up is punished in the afterlife.

That’s helpful, but you go further. You decide to throw a giant expensive party where you both invite everyone you know and make loud public vows to each other. You consider telling everyone “OK, here are some promises that we’ve designed to maximize how embarrassing it would be for us to break up”, but decide it’s better not to make that explicit. You wear jewelry at all times to indicate you’re taken, and you get everyone to agree to lose respect for you if you don’t stay together. Critically, you get everyone to agree that it’s gauche to discuss the reasons for doing all this.

It works. The two of you are so legendarily happy that everyone copies your techniques. Generations later, everyone is still doing this stuff without thinking about it, which makes it work even better.

2.

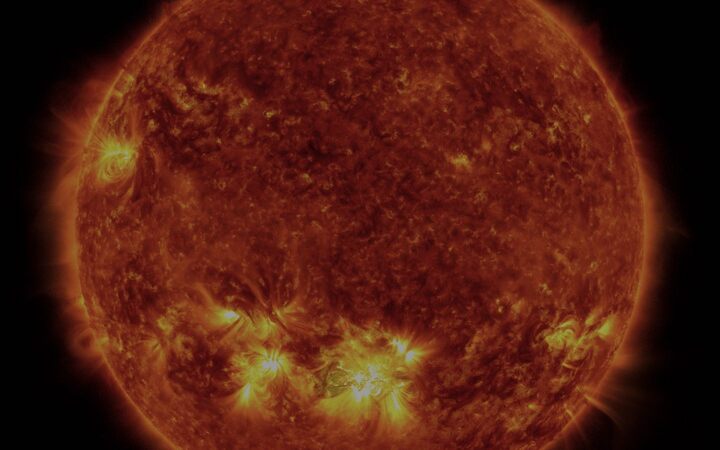

You’re worried that CO2 is going to destroy the Earth. You see two options: You can get everyone to emit less CO2, or you can do geoengineering so that CO2 doesn’t destroy the Earth so much.

You look into the details. Cutting back on CO2 emissions would clearly work, but it’s expensive and painful.

Or, you could spray sulphuric acid into the atmosphere to reflect more sunlight back into space. A few grams could change the albedo of the planet enough to offset the warming from a ton of CO2. A fleet of a few dozen jets could fly around the earth spitting out a half million tons of sulphuric acid and contain warming at a cost of only around a billion dollars a year. Except, this might worsen air pollution, destroy ozone, cause isolated droughts, and might even change the color of the sky. It wouldn’t solve problems like ocean acidification. And if you keep emitting CO2, you’ll need to put out more sulphuric acid every year and if you ever stop, the climate will abruptly change. And are you going to bet the planet on such a risky, unproven intervention?

Most of all, you’re worried about politics. Because geoengineering does have promise, if you talk about it, climate change skeptics might use it as an excuse to take no action on emissions.

And so you come to a plan: Don’t talk about geoengineering. Don’t acknowledge any promise of geoengineering. Treat anyone who talks about geoengineering with scorn. Pressure the International Panel on Climate change into not talking about it. Force everyone to solve the problem entirely by reducing CO2 emissions.

You’re pretty sure that even after doing this, humanity will still emit too much CO2 and leave the planet in peril. But, decades down the line, when humanity is well on its way to zero emissions, maybe then you can pull geoengineering out as a reserve force to save the day.

(This might be a bad plan, since feedback loops mean that geoengineering works much better if you start early, i.e. you’d rather reduce the temperature before Greenland melts into the ocean. But I emphasize that I know nothing and I’m just parroting the opinions of others.)

3.

You’re pretty sure God doesn’t exist. But you’ve read the literature. As far as you can tell, religion gives people longer, healthier, happier lives. You want in, but you don’t want to accept what you see as irrational beliefs.

So you try the alternatives. You go to some meetings of the Ethical Society, the Humanist Society, Sunday Assembly, and so on. There are some great people. But there are also a number of, umm, weirdos? You have lots of new experiences trying to force a smile while someone you just met has a long one-way discussion about Why Private Property Is Theft.

You notice that the people you most want to connect with are also the most likely to stop showing up—after all, it’s not like eternal damnation awaits anyone who quits! But the people you’re less fond of seem to have fewer social alternatives and keep coming back every week. Eventually, you stop showing up yourself.

But religion is good for you…

Eventually, you pick a relatively relaxed “normal” religion, complete with all the “God” stuff. You don’t believe everything they say is literally true, but our reality is strange and inexplicable, so who knows? There’s a great stable community and you talk about the broader themes of life and you’re healthier and happier.

You secretly guess that the group is sustained by a minority of true believers who make up critical mass for a larger group of people like you, but you never talk about this and neither does anyone else. When you have kids, you feel weird about explaining your thoughts about all this to them, but you don’t parrot back what the religion says when you’re talking about the meaning of life either.

4.

Maybe it’s the Hobo-Dyer projection or using bromine instead of chlorine in swimming pools, or the evils of ultrasonic humidifiers. Whatever it is, you and your allies are right and everyone else is wrong.

But no one listens to you. It’s not due to flaws in your arguments (they are flawless), so it must be because you’re not seen as popular and respected.

So you and your friends form a mutual admiration cabal. At first, you post things like, “This essay from Ingroup Member 29 isn’t anything special but I’m promoting it anyway to build the perceived status of our community—please read!” But everyone seems to respect you even less after this.

Slowly, you learn to always praise the content itself and to subtly promote the more charismatic people with the more attractive messages. Most importantly, you act like all this is a core activity, not something that you’re doing for strategic reasons. Slowly, other people join your group and copy your behavior, despite not being explicitly aware of its purpose.

5.

You want to be happy, but when you think about things you have edgy thoughts like life might be meaningless and no one will remember you and oh what does it all mean etc. Eventually, you decide that even if that’s true, there’s no profit in thinking about it, so you choose to believe that everything happens for a reason, and your work and family and friends and life are meaningful, and by believing in this reality you mostly seem to create it.

But still, you run into the occasional edgelord who insists on promoting a grimmer view. They annoy you: Do they think they’re wise or courageous? Do they think they’re pointing out something everyone else hasn’t thought about? All they’re doing is pushing a view that has absolutely no advantage to anyone, and ruining things for everyone who is trying to inhabit a better reality. And for what? Probably just to get some attention for themselves! But of course, saying that out loud would only help the edgelords so instead you mock them on superficial grounds to punish their defection. Slowly, you forget about your reasons for doing this, and just remember that edgelords are lame.

6.

You’re Chairman Mao in the aftermath of WWII. Most people in China get healthcare through traditional Chinese medicine. You realize that most of it, like acupuncture, probably does absolutely nothing. But you’ve got a country of 500 million people, 500 thousand doctors of traditional Chinese medicine, and only 10-20 thousand doctors of Western medicine. It would take decades to train enough Western-style doctors to care for everyone.

And what if you did launch a huge program to replace traditional Chinese medicine? At a minimum, people would get less placebo benefit from their current treatments. (And say what you want, placebo effects are real!) There might be an outcry that elites get better care than peasants. And maybe some parts of traditional Chinese medicine actually work?

So you take a different path. Instead, you call for traditional and Chinese medicine to be “unified”. You don’t say that this is because Western-style medicine is better exactly, just that it has some benefits it can bring to the table. You say things like this:

At present, doctors of Western medicine are few, and […] the broad masses of people, and in particular the peasants, rely on Chinese medicine to treat illness.

Or maybe like this:

Although we should have an all-round and correct understanding of Chinese medicine, Chinese medicine also has to transform itself. We must accept this part of our old heritage critically. To look down on Chinese medicine is not correct. To claim that everything about Chinese medicine is good, or too good, this is also not correct.

Decades later you’re funding all sorts of institutes for traditional Chinese medicine that mostly produce research that’s vaguely embarrassing, but you’ve also vastly improved the quality of care inside the country without any great disruption in the meantime.

(Or: You’re the US Senate. It’s 2013. You notice that lots of people can’t afford health care in your country, so you unanimously pass a resolution honoring the contributions of people who provide unproven, non-scientific—but cheap!—alternatives.)

Thoughts

Just to be clear, I really think that plans like these are often good, including the part where you don’t talk about them. The point of this exercise is to consider the different reasons why you shouldn’t talk.

A boring reason to keep a plan secret is so that people can’t find out about it and stop you. If I sell you 10 kilos of methamphetamines, we probably don’t want to advertise that. The above examples aren’t like that.

A more interesting reason is that you want to do things in public, but you don’t want others to know your true reasons.

Even more interesting are plans that work best if you yourself don’t understand them. For these, your best hope is that you inherit a culture that’s figured them out for you (and also forgotten about the reasons for you) so you can get the benefits just by going with the flow.

So I guess this is kind of an argument in favor of humility, or against open-mindedness. If you have high openness to experience (and if you read this without someone putting a gun to your head, you probably do) you might wonder why so many people have low openness. Maybe this is part of why.